This month’s article concerns postprocedure complications, a topic of increasing importance as we move to “value-based” reimbursement. Most practices and health systems do not have a routine process to identify complications and we have underestimated them in the past. In the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Final Rule (published in the Federal Register November 2014 – entitled CMS-1613-FC) a new measure for both the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and the Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting Program was described. Beginning in calendar year 2018, measure OP-32 will be Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate after Outpatient Colonoscopy and will be required for submission to CMS. Thus, our endoscopy units will need to understand how they might measure and reduce postprocedure complications. Dr. Francis and her colleagues have given us a choice of methods to collect such information.

John I. Allen, M.D., MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

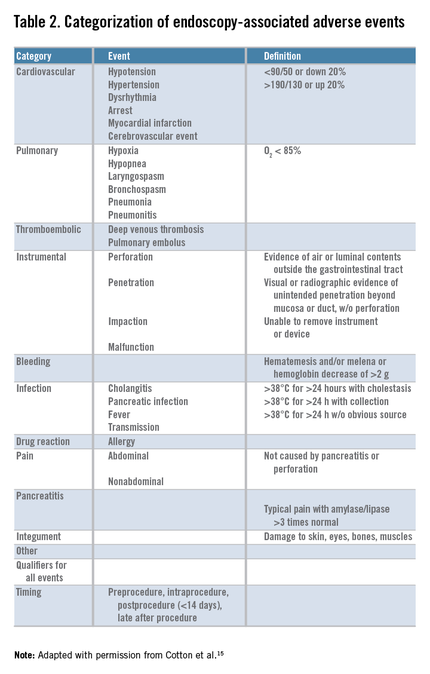

Safety is one of the most important determinants of quality in endoscopy and adverse event tracking is an effective way to monitor the safety of a procedural practice.1 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)/American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy recommends the use of a formal protocol for tracking adverse events,2,3 but provides little guidance about how this can be accomplished successfully.

Adverse events have costs associated with them. There is the real human cost of pain and suffering, but there are health care utilization costs as well. As such, adverse event rates are one outcome measure that could be part of the definition of value for a practice4 and likely will play a role in value-based purchasing.

Tracking adverse events is challenging. The best way to track adverse events might be via direct contact with the patient at a postprocedure interval beyond the window of time when an adverse event could take place, but not so remote as to hamper memory of an event.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Many authorities consider this the gold standard for event identification, but it is difficult to accomplish because it requires dedicated personnel and resources. An alternative, low-cost, sustainable means for identifying adverse events that approximates the data from direct patient contact would be attractive.

Such a program might require an infrastructure encompassing a variety of different reporting mechanisms to compensate for the lack of direct patient contact and the limitations of any individual form of reporting.14 For example, a process that relies solely on reporting from within the health care system that performed the procedure is limited to identifying patients who return to the same system for care of an adverse event. For our referral center, such a unimodal approach could miss a significant proportion of events because many of our patients live outside of our local-regional catchment area. Likewise, a system that relies solely on voluntary reporting by health care providers is limited by the providers having the time and inclination to consistently report adverse events when they encounter them.

With these issues in mind, our Gastroenterology Quality Committee created a multidisciplinary infrastructure (MDI) to track adverse events associated with our endoscopic practice. Our infrastructure uses the following. First, endoscopy nurse reporting of adverse events during or immediately after gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Our nursing staff have paper reporting cards and a voice mail event line, both of which can be used to report anything they believe is an adverse event to our Gastroenterology Quality Office. Second, an institutional website link that can be used by any health care worker in our system to electronically report an adverse event. Third, weekly electronic reminders to report adverse events that are sent to all physicians (attendings and fellows) assigned to hospital duties for gastroenterology services. Fourth, an endoscopic complication card provided to all patients at the time of their endoscopy for them to return (in a business reply envelope) if they experience an adverse event (Figure 1: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext). Fifth, an automated reporting system that identifies all patients who are admitted, for any reason, to our hospitals within 7 days of an endoscopic procedure. This process does not identify emergency room visits that do not result in a hospital admission.

Although we assumed our MDI used to track adverse events was robust, it had not been validated with another method. Our objective was to validate our MDI process of capturing adverse events by comparing it with direct patient contact via telephone.

Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minn.). We performed a prospective study to compare two mechanisms for identifying the number, type, and severity of adverse events associated with all types of inpatient and outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures.