We first initiated enhanced tracking of endoscopic adverse events in 2008, using a multimodal infrastructure that has matured since then to include the variety of sources outlined earlier. Based on the lexicon for endoscopic adverse events proposed by a recent ASGE workgroup,15 we consider an adverse event to be one that prevents the completion of the planned procedure and/or results in another procedure, subsequent medical consultation or admission to the hospital, or prolongation of an existing hospital stay. This includes obvious complications such as perforation, postpolypectomy bleeding, and post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. It also includes some less obvious situations, such as bleeding severe enough to prompt the patient to seek medical care even if an intervention is not required, and abdominal pain that leads a patient to be admitted to the hospital even if a source of pain is not identified. We also used the same group’s recommendations for grading their severity and categorizing the events (Table 1, Table 2: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext).15

In the comparative study we then attempted to contact patients by telephone who had an endoscopic procedure performed between July 26, 2011, and December 29, 2011. Three full-time study personnel contacted patients between 14 and 90 days after their procedure to inquire about adverse events that may have resulted from endoscopy. During this time, we continued our existing MDI for tracking adverse events. Events considered adverse were those plausibly associated with the procedure and severe enough for the patient to seek medical attention.

Patient contact

Our research personnel attempted to contact, by telephone, patients who had a gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure in one of our endoscopy units after at least 14 and no more than 90 days to inquire about the occurrence of adverse events. A scripted interview (Appendix A: www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)01390-1/fulltext) was used and calls were made only during business hours (between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.).

Our institution uses strict guidelines for patient contact. When a telephone call is not answered, our personnel may only leave a message stating that they are calling from the Mayo Clinic and provide a telephone number for a return call. They are not allowed to say what the call is regarding. Study personnel may make only three telephone calls before they must stop attempts to contact a patient.

Written consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board, so once a patient was contacted they could consent and be interviewed over the telephone. However, to include their information participants were required to return a signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) consent form. Without receiving a signed HIPAA consent form, the data collected for inclusion in the study could not be used.

Sample size calculation

Complications from gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures are rare events. For the purposes of our study, we believed it was important to find even small differences in the ability of the two modalities to identify adverse events. We powered this study to detect a 5% difference between the two capture mechanisms, which required a sample size of 9,894 procedures.

Statistical analysis

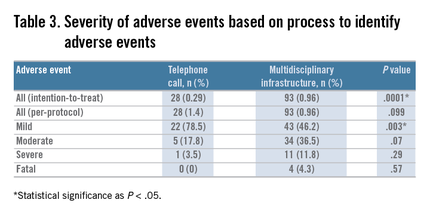

We compared the proportion of patients with adverse events as well as the type and severity of the events associated with gastrointestinal endoscopy, as identified by direct patient contact by telephone, with the proportion, type, and severity of events identified through our MDI, using the chi-square statistic for larger sample sizes (e.g., the proportion of overall adverse events in each tracking mechanism group) and the Fisher exact test for smaller sample sizes (e.g., comparing the type of adverse event in each tracking mechanism group). We used both an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis.

Costs

The study was funded by an ASGE research grant for $60,000. A total of $55,000 was spent on study personnel salary and benefits, and the sole responsibility of the study personnel was to contact patients by telephone. As stated previously, three full-time personnel contacted patients by telephone to query them about adverse events every business day for 5 months. The remaining $5000 was spent on statistical design, data entry and analysis, and administration of the study personnel.

The MDI arm of the study already was integrated into the practice. The nurse reporting was part of the job description for our nursing staff and did not require any extra hours or personnel. This also was true for physician reporting. The institutional website link and weekly electronic reminders were put into place by a medical secretary and did not require additional salary support. We estimate that it took an hour of secretarial time to create the website link and to set up weekly e-mail reminders to staff. The endoscopic complication cards that were given to all patients and returned by some of the patients cost $968 during the study period. The automated process for hospital admissions had been created previously by the infection control group in our practice. These data already were being tracked, we simply had it fed to our Quality group in the Division of Gastroenterology in addition to infection control. The upfront costs of setting up that system are not known to the authors. For our practice, registered nurses who were in a Back to Work program after injuries performed the database entry tasks with no additional salary support from our group. It typically takes 4 hours a week (or 10% of their time) to accomplish this task for a unit that performs approximately 750 endoscopic procedures a week. The adverse event tracking infrastructure was administered and analyzed by both a quality analyst and a staff gastroenterologist.