Topical lidocaine (5%) gel or ointment can facilitate use of the dilator. The patient applies a small amount to the site of vulvar pain (commonly the posterior fourchette of the introitus) with the tip of a cotton swab 15 to 30 minutes before inserting the dilator.

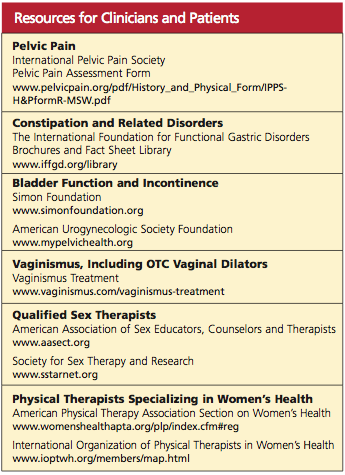

Some vaginal dilators may be obtained directly by the patient (see “Resources” box below), while others require a prescription. Graduated or vibrating dildos can be obtained at retail outlets selling sexual products. A clean finger can also be used for dilation.

Pelvic Floor Therapy

Several modalities offered by specialized physical therapists are used to improve pelvic and vulvovaginal blood flow and control over the pelvic musculature. This may help to alleviate pain with intercourse, particularly in patients with signs of pelvic floor weakness, poor muscle control, or instability. Modalities include pelvic floor exercises and manual therapy techniques (eg, transvaginal trigger point therapy, transvaginal and/or transrectal massage, dry needling of a trigger point).4,58 Surface electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor musculature is also used to decrease pain and muscle spasm.59

Kegel exercises60 (ie, tensing and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles) may help a patient gain control over both contraction and relaxation of the pelvic muscles.60,61 However, if palpation of the pelvic floor reveals tight, inelastic, and dense tissue, assessment and grading of muscle strength may be misleading. For example, the pelvic floor may demonstrate a state of constant contraction (hypertonicity or a “short pelvic floor”).62 Attempts at voluntary contraction of a muscle in this state may be perceived and graded incorrectly as weak.

Traditional Kegel exercises are contraindicated in women with muscle hypertonicity and an inability to relax these muscles. Some practitioners use the term “reverse Kegel” to describe active, bearing-down exercises that increase pelvic floor relaxation. Biofeedback training (surface EMG and/or rehabilitative ultrasound imaging) can be useful to reeducate resting muscle tone of the pelvic floor. Breathing, tactile, verbal, and imagery cues are essential.61,62

Cognitive Behavioral Sex Therapy

This specialized form of psychotherapy helps patients identify cognitive, emotional, and relationship factors that contribute to their pain. Patients learn coping strategies, including relaxation techniques and modification of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to reduce anxiety, tension, and pain. As pain management improves, the focus shifts to enhancing sexual functioning, including restarting the sexual relationship if sex has been avoided because of pain.63

WHEN AND WHERE TO REFER

Referral is appropriate if the patient’s condition worsens, is unresponsive to therapy, or requires specialized evaluation and treatment. Sex therapy, psychotherapy, or couples counseling may be indicated in more complex cases in which a sexual disorder and significant psychologic and/or relationship problems coexist. Examples may include an unresolved history of sexual abuse, clinical anxiety or depression, sexual phobia or aversion, and general relationship distress. To locate qualified sex therapists, see the “Resources” box.

Physical therapy may be prescribed if the patient demonstrates or reports persistent pain or lack of improvement with initial pelvic floor therapy, an inability to use a dilator on her own, or increased pain or perceived tightness while using a dilator; or if she develops pelvic or perineal pain at rest. To locate specially trained physical therapists, see the “Resources” box.

CONCLUSION

Though commonly seen in primary care, sexual pain disorders in women are often difficult to diagnose and treat because of the confusing array of possible contributory factors. This article presents an overview of possible presentations, causes, diagnostic strategies, and treatment options, integrating evidence-based approaches from the fields of medicine, psychology, and physical therapy.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DMS-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:554-558.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8): 762-774.

3. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177-183.

4. Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS, Cummings BD. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:vol 2, chap 6:110-131.

5. Perry CP. Vulvodynia. In: Howard FM, Perry CP, Carter JE, El-Minawi AM, eds. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000:204-211.

6. Glazer HI, Jantos M, Hartmann EH, Swencioniswom C. Electromyographic comparisons of the pelvic floor in women with dysesthetic vulvodynia and asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(11):959-962.

7. Binik YM. The DSM diagnostic criteria for vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):278-291.