Not all patients with panic attacks respond well to CBT; predictors of poor response in clinical trials have included:

- severe baseline panic symptoms, personality disorders, and possibly depressed mood

- marital dissatisfaction

- low motivation for treatment.2,9

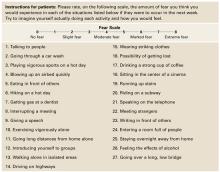

Figure Patient assessment: Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire

Source: Reprinted with permission from Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1995;1:114-22. Copyright 1995, Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Cognitive Therapies for Panic Disorder

Psychoeducation. Begin by defining and explaining anxiety, panic attacks, panic disorder, and any comorbid psychopathology the patient may have (agoraphobia, depression). Explain panic symptoms as physiologic and psychological responses to stressors.

Address the patient’s fears that anxiety’s physiologic symptoms represent a serious or undiagnosed medical disorder or that a panic attack could cause serious harm. Assign self-help and reading materials to reinforce this discussion (see Related resources). Finally, explain the rationale for using CBT to treat panic symptoms.

Use cognitive restructuring to address faulty or irrational information-processing patterns that underlie pathologic anxiety. Identify automatic thought patterns (such as catastrophizing, overgeneralization, all-or-nothing thinking, and personalization), then provide a careful “reality check,” in which you systematically substitute a more-rational thought process.

Have the patient keep a self-monitoring diary to help you assess thought patterns and re-direct irrational thoughts. A diary may identify anxiety-provoking scenarios on which to focus therapy. Encourage patients to document anxiety events using the “triple-column” technique:23

- column 1: circumstances of the anxiety or panic

- column 2: their emotional state at the time

- column 3: any thoughts they can identify.

Instruct them to log this data while experiencing symptoms or immediately afterward. Later, during the intervention phase, patients can record how they tried to restructure their thoughts and any consequent mood changes. Review diary entries with them during subsequent sessions.

Exposure Therapy

Graduated exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the core component of CBT for panic disorder. ERP exercises require the patient to confront anxiety-producing stimuli while agreeing not to engage in maladaptive behavior that avoids, prematurely reduces, or prevents the anxiety. The stimuli may be external cues—such as bridges, stores, or heights—or interoceptive cues such as dizziness, tachycardia, or tachypnea.

Creating fear hierarchies. To begin, we recommend that you work with the patient to create lists of all external situations and interoceptive stimuli that cause him or her anxiety. Separating the stimuli into two lists helps patients recognize that their bodily stimuli are at least as important as environmental stimuli in promoting a panic attack.

The patient then rates each stimulus using a Subjective Units of Distress scale (SUDS)—assigning 0 to 100 points from no anxiety to overwhelming anxiety—and ranks items on the lists from mildest to worst anxiety. Instruct patients to rate the distress they would feel if they could not escape from the stimuli.

First experience. After the hierarchies are created, the therapist introduces the patient to exposure therapy by choosing an item that causes mild to moderate anxiety. Starting at this anxiety level, patients are likely to succeed with their first exercise without feeling overwhelmed. The therapist teaches the patient about the process, then begins the exposure by helping the patient create and confront the very scenario (or a representation of that scenario) that causes anxiety.

When working on interoceptive cues, various exercises can be used to reproduce bother-some bodily symptoms, such as:

- running up a flight of stairs or running in place to generate tachycardia

- purposefully hyperventilating to produce lightheadedness.

- spinning in place to create dizziness.

The patient agrees not to actively attempt to escape the scenario but to tolerate and perhaps even focus on the anxiety (Box 3). Using “safety cues”—such as leaning against a wall or keeping eyes closed—is also forbidden. Patients soon see that the anxiety does not last indefinitely but begins to diminish fairly rapidly.

Reaching the goal. After repeated exposure sessions, anxiety associated with a stimulus begins to extinguish. Having experienced the success of tolerating a previously difficult stimuli and feeling much less anxious, the patient is ready to take on increasingly difficult tasks. The therapist also assigns the patient “homework” to practice exposure exercises already mastered during sessions. As exposure therapy progresses, the patient takes a larger role in designing and executing sessions. The goal is for the patient to learn to become his or her own behaviorist and to intervene early when panic symptoms begin.

Resist temptation to rescue patients from their anxiety during exposure sessions, such as by chatting about the weather or current events or providing other distractions. To extinguish the link between the stimuli and anxiety, the patient must experience anxiety all the way through the exercise—preferably giving ongoing Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) ratings—until symptoms inevitably wane and cease.

Similarly, avoid assigning exposure homework to be done “until you can’t stand it anymore, then take a rest.” Although well-intentioned, allowing the patient to escape the exposure when anxiety peaks increases conditioned anxiety and strongly reinforces avoidance behaviors.