The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States has posed significant barriers in care for perinatal patients and has been attributed to financial barriers, medicolegal risk, staffing, and safety concerns.29 Though currently there are no MBUs in the US, other specialized units have been created. A partial day hospitalization program created in 2000 in Rhode Island for mothers and infants revolutionized the psychiatric care experience for new mothers.30 Since then, other institutions have significantly expanded their services to include perinatal psychiatry inpatient units, yet unlike MBUs, these units typically do not provide overnight rooming-in with infants.31 They have the necessary resources and facilities to accommodate the mother’s needs and maximize positive mother-infant interaction, while actively integrating the infant into the mother’s treatment. Breast pumping is treated as a necessary medical procedure and patients can easily access hospital-grade breast pumps with staff supervision. At one such perinatal psychiatric inpatient unit, high rates of treatment satisfaction and significant improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, active suicidal ideation, and overall functioning were observed at discharge.32 Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate strategies in general psychiatry units to improve perinatal care, acknowledging that most patients will not have access to these specialized units.21

A framework to approaching the relational ethics decisions

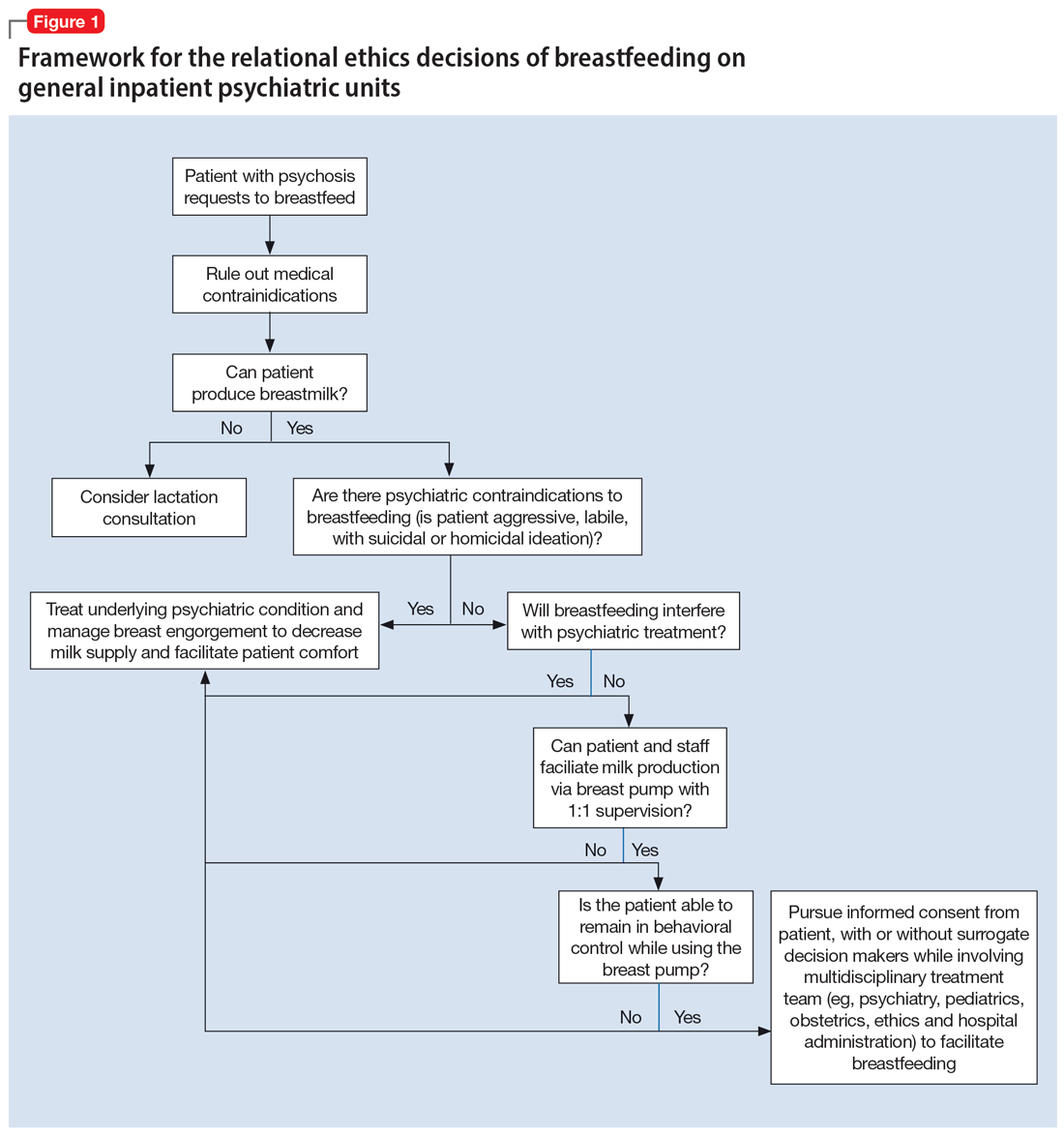

An interdisciplinary team used a relational ethics perspective to carefully analyze the risks and benefits of these complex cases. In Figure 1, we propose a framework for the relational ethics decisions of breastfeeding on general inpatient psychiatric units. In creating this framework, we considered principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence, along with the medical and logistical barriers to breastfeeding.

In Ms. C’s case, the team determined that the risks—which included disrupting the mother’s psychiatric treatment, exposing her to psychological harm due to increasing attachment before remanding the child to CPS custody, and risks to the child due to potential unpredictable agitation driven by the treatment-refractory psychosis of the mother as well as that of other psychiatric patients—outweighed the benefits of breastfeeding. We instead recommended breast pumping as an alternative once Ms. C’s psychiatric stability improved. We presented Ms. C with the option of breast pumping on postpartum Day 5. During a 1-day period in which she showed improved behavioral control, she was counseled on the risks and benefits of breastfeeding and exclusive pumping and was notified that the team would help her with the necessary resources, including consultation with a lactation specialist and breast pump. Despite lactation consultant support, Ms. C had low milk production and difficulty with hand expression, which was very discouraging to her. She produced 1 ounce of milk that was shared with the newborn while in the NICU. Because Ms. C’s psychiatric symptoms continued to be severe, with lability and aggression, and because pumping was triggering distress, the multidisciplinary team determined the best course of care would be to focus on her psychiatric recovery rather than on pumping breastmilk. To reduce milk production and minimize discomfort secondary to breast engorgement, the lactation consultant recommended cold compresses, pain management, and compression of breasts. Ultimately, the mother-infant dyad was unable to reap the benefits of breastfeeding (via pumping or direct breastfeeding) due to the mother’s underlying psychiatric illness, although the staffing, psychosocial support, and logistical limitations contributed to this outcome.33

In Ms. S’s case, the treatment team determined that there were no medical or psychiatric contraindications to breastfeeding, and she was counseled on the risks and benefits of direct breastfeeding and pumping. The treatment team determined it was safe for Ms. S to directly breastfeed as there were no concerns for infant harm postdelivery with constant supervision while on the obstetrics floor. The patient opted to directly breastfeed, which was successful with the guidance of a lactation specialist. When she was transferred to the psychiatric unit on postpartum Day 2, her child was discharged home with the husband. The patient was then encouraged to pump while the psychiatrists monitored her symptoms closely and facilitated increased staff and resources. Transportation of breastmilk was made possible by the family, and on postpartum Day 5, as the patient maintained psychiatric stability, the team discussed with Ms. S and her husband the prospect of direct breastfeeding. The treatment team arranged for separate visitation hours to minimize the possibility of exposing the infant to aggression from other patients on the unit and advocated with hospital leadership to approve of infant visitation on the unit.

Impact of involvement of Child Protective Services

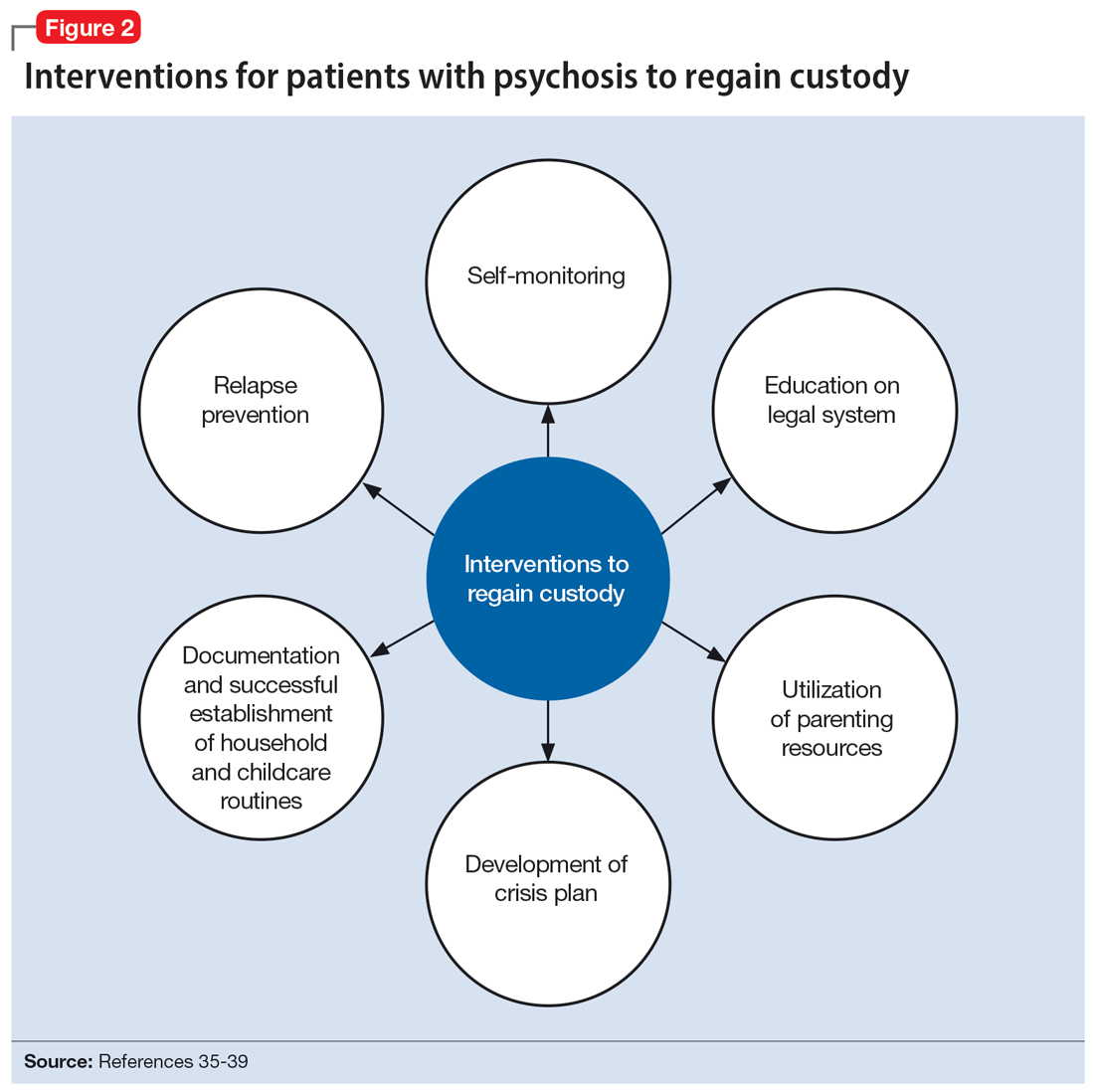

The involvement of CPS also added complexity to Ms. C’s case. Without proper legal guidance, mothers with psychosis who lose custody can find it difficult to navigate the legal system and maintain contact with their children.34 As the prevalence of custody loss in mothers with psychosis is high (approximately 50% according to research published in the last 10 years), effective interventions to reunite the mother and child must be promoted (Figure 2).35-39 Ultimately, the goal of psychiatric hospitalization for perinatal women who have SMI is psychiatric stabilization. The preemptive involvement of psychiatry is crucial because it can allow for early postpartum planning and can provide an opportunity to address feeding options and custody concerns with the patient, social supports and services, and various medical teams. In Ms. C’s case, she visited her baby in the NICU on postpartum Day 2 without consultation with psychiatry or CPS, which posed risks to the patient, infant, and staff. It is vital that various clinicians collaborate with each other and the patient, working towards the goal of optimizing the patient’s mental health to allow for parenting rights in the future and maximizing a sustainable attachment between the parent and child. In Ms. S’s case, the husband was able to facilitate caring for the baby while the mother was hospitalized and played an integral role in the feeding process via pumped breastmilk and transport of the infant for direct breastfeeding.

Continue to: The differences in these 2 cases...