Approaching care with a relational ethics framework

A relational ethics framework was constructed to evaluate whether to support breastfeeding for both patients during their psychiatric hospitalizations. A relational ethics perspective is defined as “a moral responsibility within a context of human relations” [that] “recognizes the human interdependency and reciprocity within which personal autonomy is embedded.”2 This framework values connectedness and commonality between various and even conflicting parties. In the setting of a clinician-patient relationship, health care decisions are made with consideration of the patient’s traditional beliefs, values, and principles rather than the application of impartial moral principles. For these complex cases, this framework was chosen to determine the safest possible outcome for both mother and child.

Risks/benefits of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI

There are several methods of breastfeeding, including direct breastfeeding and other ways of expressing breastmilk such as pumping or hand expression.3 Unlike other forms of feeding using breastmilk, direct breastfeeding has been extensively studied, has well-established medical and psychological benefits for newborns and mothers, and enhances long-term bonding.4 Compared with their counterparts who do not breastfeed, mothers who breastfeed have lower rates of unintended pregnancy, cardiovascular disease, postpartum bleeding, osteoporosis, and breast and ovarian cancer.5 Among its key psychological benefits, breastfeeding is associated with an increase in maternal self-efficacy and, in some research, has been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression and stress. Additionally, breastfed infants experience lower rates of childhood infection and obesity, and improved nutrition, cognitive development, and immune function.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes these benefits and recommends that women exclusively breastfeed for 6 months postpartum and continue to breastfeed for 2 years or beyond if mutually desired by the mother and child.7 Absolute contraindications to breastfeeding must be ruled out (eg, infant classic galactosemia; maternal use of illicit substances such as cocaine, opioids, or phencyclidine; maternal HIV infection, etc).

The risks of breastfeeding by patients who have SMI must also be considered. In severe situations, the infant can be exposed to a mother’s agitation secondary to psychosis.8,9 The transmission of antipsychotic medication through breastmilk and associated adverse effects (eg, sedation, poor feeding, and extrapyramidal symptoms) are also potential risks and varies among different antipsychotic medications.1,10 Therefore, when prescribing an antipsychotic for a patient with SMI who breastfeeds, it is crucial to consider the medication’s safety profile as well as other factors, such as the relative infant dose (the weight-adjusted [ie, mg/kg] percentage of the maternal dosage ingested by a fully breastfed infant) and the molecular characteristics of the medication.10-12 Neonates should be routinely monitored for adverse effects, medication toxicity, and withdrawal symptoms, and care should be coordinated with the infant’s pediatrician. Certain antipsychotic medications, such as aripiprazole, may impact breastmilk production through the dopamine agonist’s interference of the prolactin reflex and anticholinergic properties.11,13 For a patient with SMI, perhaps the most significant risk involves the time and resources needed for breastfeeding, which can interfere with sleep and psychiatric treatment and possibly further exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.14-16 Additionally, breastfeeding difficulties or disruption can increase the risk of psychiatric symptoms and psychological distress.17 In Ms. C’s case, there was a delay in the baby latching as well as multiple medical and psychiatric factors that hindered the milk-ejection reflex to properly initiate; both of these factors rendered breastfeeding particularly difficult while Ms. C was on the inpatient psychiatry unit.17 In comparison, Ms. S was able to bond with her infant shortly after delivery, which facilitated the milk-ejection reflex and lactation.

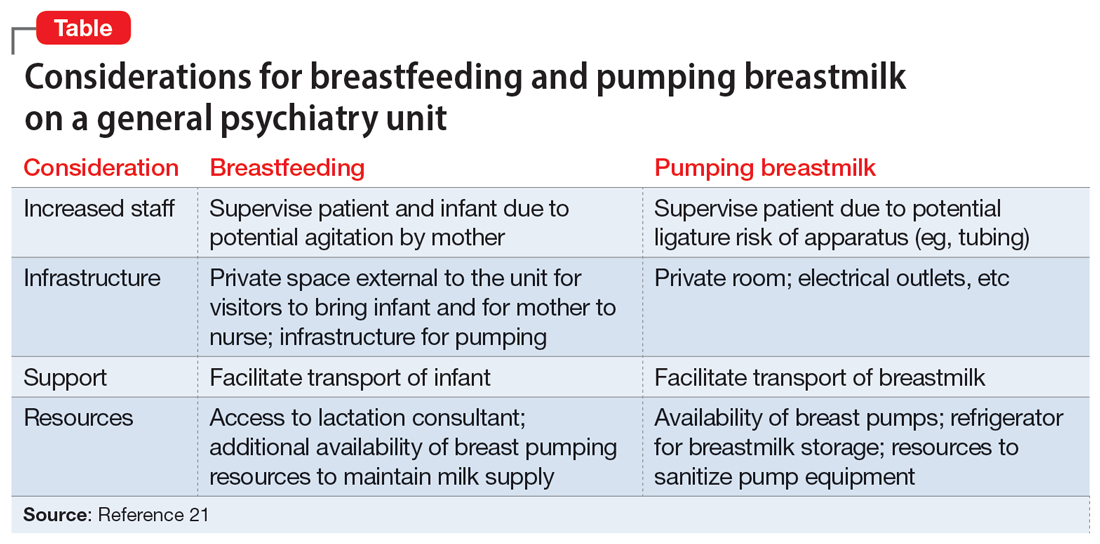

Patients who wish to directly breastfeed but struggle to do so while tending to their acute psychiatric condition can benefit from expression of breastmilk that can be provided to the infant or discarded to facilitate breastfeeding in the future.18 While expression of breastmilk may not be as advantageous for infant health as direct breastfeeding due to the potential changes in breastmilk composition from collecting, storing, and heating, this option can be more protective than formula feeding and facilitate future breastfeeding.19 In these clinical scenarios, it is standard care to provide a hospital-grade breast pump to the patient, much like a continuous positive airway pressure machine is provided to patients with obstructive sleep apnea.20 However, there is often considerable difficulty obtaining proper breastfeeding equipment and a lack of services devoted to perinatal care in general inpatient settings. Barriers to direct breastfeeding and pumping of breastmilk are highlighted in the Table.21

Limitations on breastfeeding on an inpatient unit

The limitations in care and restrictions placed on breastfeeding are more optimally addressed in a mother and baby unit (MBU). MBUs are specialized inpatient psychiatric units designed for mothers experiencing severe perinatal psychiatric difficulties. Unlike general psychiatric units, MBUs allow for joint, full-time admission of mothers and their infants. These units also include multidisciplinary staff who specialize in treating perinatal mental health issues as well as infant care and child development.22 Admission into an MBU is considered best practice for new mothers requiring treatment, particularly in the United Kingdom, Australia, and France, as it is well-recognized that the separation of mother and baby can be psychologically harmful.23 In the UK, most patients admitted to an MBU showed significant improvement of their psychiatric symptoms and reported overall high satisfaction with care.24,25 Patients who experience postpartum psychosis prefer MBUs over general psychiatric units because the latter often lack specialized perinatal support, appropriate visitor arrangements, and adequate time with their infant.26-28

Continue to: The resistance to adopting MBUs in the United States...