TREATMENT Adding long-acting haloperidol

Ms. A had previously achieved therapeutic blood levels9 with oral haloperidol. Data suggest that compared with the oral form, long-acting injectable antipsychotics can both improve compliance and decrease rehospitalization rates.10-12 Because Ms. A previously had done well with haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 2 weeks, achieving a blood level of 16.2 ng/mL, and because she had a partial response to oral haloperidol, we add haloperidol decanoate, 100 mg every 2 weeks, to her regimen, with the intention of transitioning her to all-depot dosing. In addition, the treatment team tries to engage Ms. A in a discussion of potential psychological contributions to her current presentation. They note that Ms. A has her basic needs met on the unit and reports feeling safe there; thus, a fear of discharge may be contributing to her lack of engagement with the team. However, because of her limited communication, it is challenging to investigate this hypothesis or explore other possible psychological issues.

Despite increasing the dosing of haloperidol, Ms. A shows minimal improvement. She continues to stonewall her treatment team, and is unwilling or unable to engage in meaningful conversation. A review of her chart suggests that this hospital course is different from previous ones in which her average stay was a few weeks, and she generally was able to converse with the treatment team, participate in discussions about her care, and make decisions about her desire for discharge.

The team considers if additional factors could be impacting Ms. A’s current presentation. They raise the possibility that she could be going through menopause, and hormonal fluctuations may be contributing to her symptoms. Despite being on the unit for nearly 2 months, Ms. A has not required the use of sanitary products. She also reports to nursing staff that at times she feels flushed and sweaty, but she is afebrile and does not have other signs or symptoms of infection.

The authors’ observations

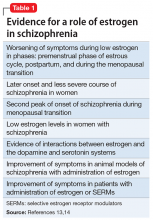

Evidence suggests that estrogen levels can influence the development and severity of symptoms of schizophrenia (Table 113,14). Rates of schizophrenia are lower in women, and women typically have a later onset of illness with less severe symptoms.13 Women also have a second peak incidence of schizophrenia between ages 45 and 50, corresponding with the hormonal changes associated with menopause and the associated drop in estrogen.14 Symptoms also fluctuate with hormonal cycles—women experience worsening symptoms during the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle, when estrogen levels are low, and an improvement of symptoms during high-estrogen phases of the cycle.14 Overall, low levels of estrogen also have been observed in women with schizophrenia relative to controls, although this may be partially attributable to treatment with antipsychotics.14

Estrogen affects various regions of the brain implicated in schizophrenia and likely imparts its behavioral effects through several different mechanisms. Estrogen can act on cells to directly impact intracellular signaling and to alter gene expression.15 Although most often thought of as being related to reproductive functions, estrogen receptors can be found in many cortical and subcortical regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, substantia nigra, and prefrontal cortex. Estrogen receptor expression levels in certain brain regions have been found to be altered in individuals with schizophrenia.15 Estrogen also enhances neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, playing a role in learning and memory.16 Particularly relevant, estrogen has been shown to directly impact both the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems.15,17 In animal models, estrogen has been shown to decrease the behavioral effects induced by dopamine agonists and decrease symptoms of schizophrenia.18 The underlying molecular mechanisms by which estrogen has these effects are uncertain.