FIGURE 4A Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4B Deliver the fetal head

FIGURE 4C Deliver the fetal head

Uterine incision: 1-layer, in situ close

Remove the placenta only after it separates spontaneously—this greatly reduces blood loss compared with immediate manual placental delivery or umbilical-cord traction. Manually deliver the placenta only if it has not separated spontaneously after 5 minutes. Avoid routine manual clean-out of the uterine cavity if the placenta is completely delivered.1-3,14

Dilate the cervix to facilitate lochial discharge, when necessary.

Decrease uterine bleeding by massaging the uterus and administering diluted oxytocin.

Close the uterine incision in situ. Disadvantages of routine uterine exteriorization include discomfort and vomiting resulting from traction, exposure of the fallopian tubes to unnecessary trauma, increased risk of infection, possible rupture of the uteroovarian veins, and pulmonary embolism.

Exteriorization may also increase the risk of adhesion formation by exposing the uterine serosa to the abrasive effects of drying or microscopic abrasion if sponges are used to hold the uterus in place.1,14-17

Use a single-layer closure with a running suture of polyglycolic acid to close the uterine incision (FIGURE 5A). If needed, use atraumatic clamps to grasp the edges of the hysterotomy to facilitate visualization and closure.

Begin suturing at a point just beyond one end of the incision, continuing to the opposite side. Be sure to penetrate the full thickness of the myometrium and avoid incorporating the decidua in the suture line. After the uterine closure, use individual figure-of-8 sutures to control areas of persistent bleeding.

Compared with 2-layer closures, single-layer closure of a low transverse incision is associated with reduced operating time, improved hemostasis, and less tissue disruption; introduces less foreign material into the surgical site; reduces the need for postoperative analgesia; and potentially reduces infectious morbidity. A trial of labor after a cesarean section with 1-layer closure appears safe.18-22

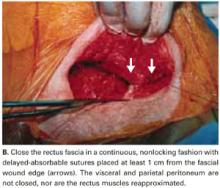

We do not close the vesicouterine fold and parietal peritoneum (FIGURE 5B) or reapproximate the rectus muscles. It has been shown that a new peritoneal layer is formed within days of the original incision closure.

Leaving the peritoneum open leads to no increased postoperative complications, nor obvious differences in wound healing, wound dehiscence, or incidence of postoperative adhesions. Compared to women without peritoneal closure, those with peritoneal closure require a longer operative time, greater amounts of post-operative narcotics for postoperative pain, a greater need for bowel stimulants, and a longer postoperative hospitalization.23

In 1995, we performed laparoscopy for gynecologic conditions in 23 patients and repeat cesarean in 10 patients who had undergone our technique (with visceral and parietal peritoneum left open).2 We found no adhesions and a normal peritoneal lining in all cases.

In 1 subgroup, peritoneal closure is strongly recommended: cases in which 1 or both rectus muscles have been transected to increase surgical exposure. Extremely thick fibromuscular adhesions between the low anterior surface of the uterus and the under-surface of the rectus musculature may develop if the parietal peritoneum is not closed.

FIGURE 5A Close the incisions

FIGURE 5B Close the incisions

Abdominal closure

Close the rectus fascia with a continuous nonlocking 0 suture after the rectus muscles fall into place. Place entry and exit sites at 1-cm intervals, 1.5 cm beyond the wound edges—this minimizes the risk of sutures pulling through fascia. Interrupted sutures offer no greater tensile strength than continuous suturing.24 Tight, continuous suturing can lead to tissue ischemia, which may weaken the sutured fascia, and thus should be avoided.

The subcutaneous layer is not closed separately. One exception is obese patients with at least 2 cm of thick subcutaneous tissue. Thickness of subcutaneous tissue appears to be a significant risk factor for wound infection after cesarean section.25

In patients with thick subcutaneous tissue, you can reduce tension on the skin edges and the risk of subcutaneous infection, seroma formation, and wound disruption by placing interrupted 3-0 absorbable synthetic sutures to eliminate dead space.26-28 We have found no need to place Penrose drains or closed drainage systems in the subcutaneous layer.29-31

Close the skin using a subcuticular continuous absorbable 4-0 suture or, alternatively, metal staples, which are removed 4 days after surgery (FIGURE 5C).

FIGURE 5C Close the incisions

Prompt postoperative recovery

The patient may drink fluids in the recovery room, can resume a regular solid food diet within 4 hours after surgery, and may resume mobility as soon as anesthesia wears off.

Early breast-feeding is also allowed in the recovery room. In our experience, this has not been associated with complications, has been highly appreciated by the patients, and has led to earlier hospital discharge.