Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

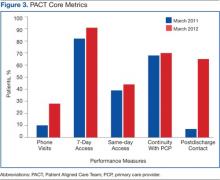

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

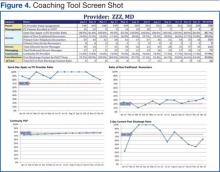

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.