One might logically question whether evidence exists at all to support a physician addressing spiritual issues. Several authors have thoroughly reviewed the evidence for a connection between spiritual commitment and health outcomes.19-21 It is not our intent to repeat their effort here. However, in reviewing their findings, we were struck by the varying quality of evidence found in the medical literature. In some cases, spiritually related actions are supported by abundant evidence; other spiritual practices lack sufficient data for recommendation in the clinical setting. As empirical evidence accumulates, physicians will be increasingly able to discern the therapeutic benefit of certain faith-based practices. Evidence alone, however, does not establish an ethical imperative to address a patient’s spiritual or faith-based practices. The physician’s belief, medical and patient values, and available time must also be taken into account.

Principle of belief

Belief in a given therapy, by both the patient and the physician, is a major part of successful doctor-patient interactions. Researchers recognize that a caregiver’s belief or disbelief in a given therapy can significantly alter a patient’s response to treatment; otherwise there would be no need to double-blind studies.

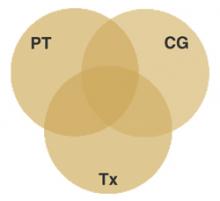

The principle of belief, illustrated in Figure 1, states a spiritual adjunct to therapy is maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief, the caregiver’s belief, and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy. Conversely, a spiritual adjunct to treatment is less appropriate when the principle of belief is violated by caregiver incongruence, patient incongruence, incongruence of therapy, or extreme incongruence of the caregiver, patient, and therapy.

FIGURE 1

Congruence of belief

Spiritual adjuncts to therapy are maximally beneficial when congruence exists between the patient’s belief (PT), the caregiver’s belief (CG), and the relevance of that shared belief to therapy (Tx).

A physician may respectfully observe and document the faith-based practices of a patient without supporting or criticizing these practices. Encouraging or integrating the patient’s faith-based practices into therapy, however, requires a personal judgment concerning how the patient’s beliefs and those of the caregiver are relevant to a medical condition. Even in cases of incongruence, using this model may lead to serendipitous therapeutic options as a caregiver and patient work together to find common ground for relevant recommendations.

Principle of quality care

The principle of quality care states that a patient’s spiritual beliefs are most appropriately incorporated into therapy when and if doing so improves the quality of care received by the patient.

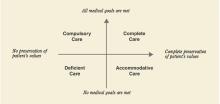

A popular definition characterizes quality care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes....”22 Many definitions of quality care share this narrow focus on health outcomes. However, patients may more broadly define quality of care by including the degree to which personal values are preserved. A comprehensive definition of quality care, illustrated in Figure 2, takes into account both desired health outcomes and the patient’s values.

Complete care occurs when medical goals are achieved and the patient’s values are preserved.

Accommodative care occurs when medical treatment is adjusted for the sake of a patient’s values, as when a patient declines vaccination or other therapies for religious reasons.

Compulsory care describes forced medical therapy without preservation of the patient’s values. This type of care may result from conflicts between religious beliefs and medical standards leading to a patient being treated against his or her will. The adverse effects of compulsory care can be minimized by a thorough patient history that includes questions concerning personal beliefs that may conflict with standard treatment.

Deficient care, defined as failure to achieve medical goals while also violating patient values, can result from poor medical management, patient non-adherence, or lack of communication.

During any clinical encounter, the caregiver’s ultimate goal should be to provide complete care. Accommodative care and compulsory care may be necessary at times, but deficient care should always be avoided.

FIGURE 2

Criteria for defining quality of care

Principle of time

Research underscores the commonly recognized relation between longer consultations and general satisfaction among patients.23,24 Yet time is too often a clinical luxury. Primary care physicians report lack of time as a barrier to providing a variety of potentially beneficial preventive services, including basic counsel on health issues,25-26 despite evidence that brief physician advice can lead to changes in a patient’s health behaviors.27 Similarly, family physicians28 report lack of time as the number one barrier to discussions of spiritual issues.

Generally, preventive health counseling in a primary care setting increases the length of time with a patient anywhere from 2.5 to 3.8 minutes.26,29 Time like this must be taken into account when weighing the importance of addressing spiritual issues with one patient against the time committed to other patients.