The Big Picture

As first-trimester screening evolves with technologic developments to become more comprehensive and precise, one of its ever-important components involves the art of history taking, physician-patient dialogue, and the incorporation of low-tech risk assessments for coping with and possibly preventing preterm labor and delivery.

Measuring the cervix at this very early stage is not a good predictor of its ability to contain the pregnancy for the rest of the gestation or even until a reasonably mature gestation is reached. In the first trimester, the cervix generally is not under enough pressure from the weight of the pregnancy to disclose whether it is a strong or weak cervix or whether it has the potential to shorten in an extreme way or not. This is different from measuring the cervix later in pregnancy when the shortening process has already started, and when intervention is based on proven results.

The first trimester is an excellent time, however, to have the mother recount her history. It is also a good time to make decisions about the use of progesterone, which in weekly injections has been shown to reduce the incidence of preterm delivery, and to institute a serial monitoring program so that any changes may be detected before the patient presents with rapidly advancing preterm labor, i.e., before a clinical emergency.

Such dialogue and interaction emphasizes to me the importance of a team approach to first-trimester screening that involves the ob.gyn. physicians, well-trained sonographers, well-trained perinatal nurses, and perinatologists who specialize in high-risk maternal and fetal complications.

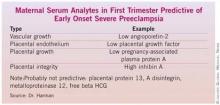

Prenatal screening is no longer an in-and-out assessment of two or three measures. That began to change more than 5 years ago with adoption of the first-trimester screening approach combining biochemistry and imaging. It continues to evolve as prenatal screening provides an even more thorough and comprehensive view of fetal, placental, and maternal function that allows us to thoroughly map out the care of our patients. For women who have normal pregnancies, this is incredibly reassuring. And for those with any kind of outlying results or overt complications, it provides a starting point for making the best of even the most challenging pregnancies.

Dr. Harman is professor and interim chair of the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as director of the school’s maternal-fetal medicine division. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.