Comorbidities

Prurigo nodularis has been associated with a wide array of comorbidities; however, the direction of the relationship between PN and these conditions makes it difficult to discern if PN is a primary or secondary condition.29 Prurigo nodularis commonly has been connected to other inflammatory dermatoses, with a link to atopic dermatitis being the strongest.5,29 However, PN also has been linked to other pruritic inflammatory cutaneous disorders, including psoriasis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, lichen planus, and dermatitis herpetiformis.14,29

Huang et al14 found an increased likelihood of psychiatric illnesses in patients with PN, including eating disorders, nonsuicidal self-injury disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Treatments directed at the neural aspect of PN have included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which also are utilized to treat these mental health disorders.

Furthermore, systemic diseases also have been found to be associated with PN, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14 The relationship between PN and systemic conditions may be due to increased systemic inflammation and dysregulation of neural and metabolic functions implicated in these conditions from increased pruritic manifestations.29,30 However, studies also have connected PN to infectious conditions such as HIV. One study found that patients with PN had 2.68 higher odds of infection with HIV compared to age- and sex-matched controls.14 It is unknown if these conditions contributed to the development of PN or PN contributed to the development of these disorders.

Clinical Presentations

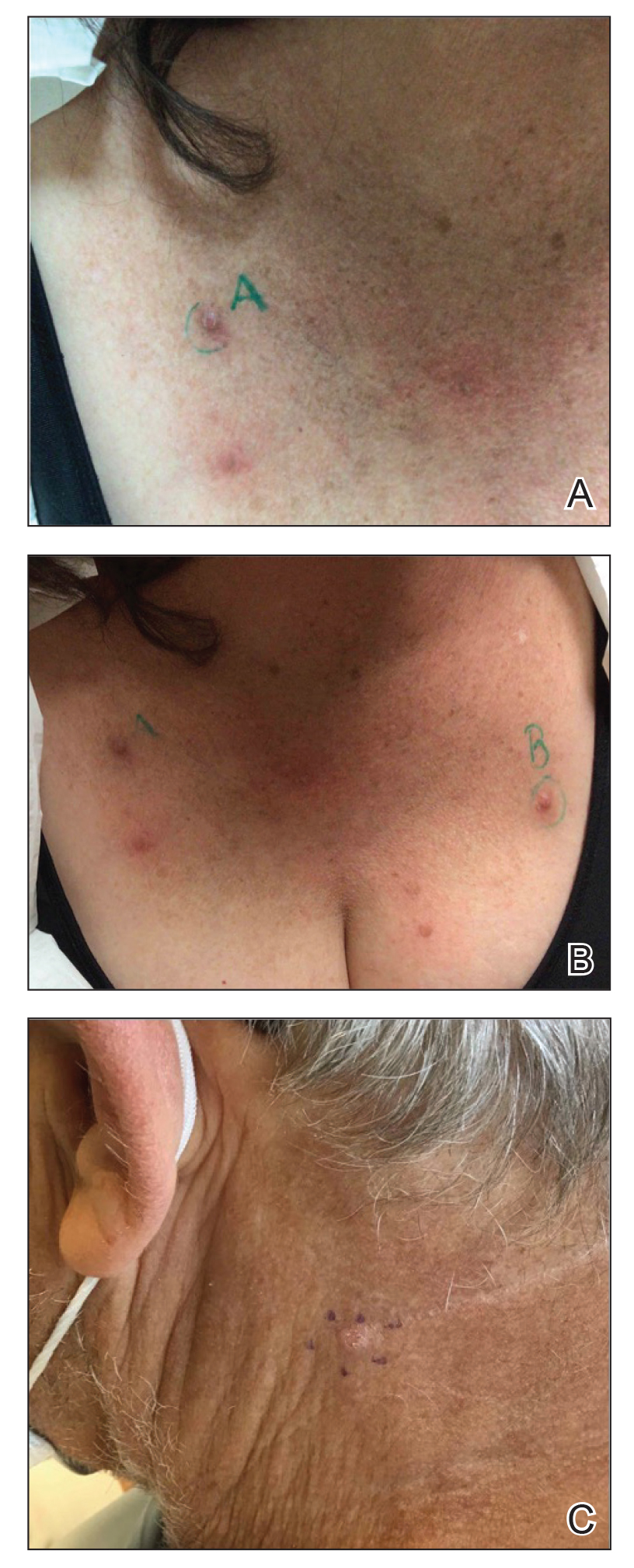

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically manifests with multiple severely pruritic, dome-shaped, firm, hyperpigmented papulonodules with central scale or crust, often with erosion, due to chronic repetitive scratching and picking secondary to pruritic systemic or dermatologic diseases or psychological disorders (Figure 2).1,2,4,5,8,31 Most often, diagnosis of PN is based on history and physical examination of the lesion; however, biopsies may be performed. These nodules commonly manifest with ulceration distributed symmetrically on extensor extremities in easy-to-reach places, sparing the mid back (called the butterfly sign).8 Lesions—either a few or hundreds—can range from a few millimeters to 2 to 3 cm.8,32 The lesions differ in appearance depending on the pigment in the patient’s skin. In patients with darker skin tones, hyperpigmented or hypopigmented papulonodules are not uncommon, while those with fairer skin tones tend to present with erythema.31

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the variation in manifestation of PN, these lesions may resemble other cutaneous conditions. If the lesions are hyperkeratotic, they can mimic hypertrophic lichen planus, which mainfests with hyperkeratotic plaques or nodules on the lower extremities.8,29 In addition, the histopathology of lichen planus resembles the appearance of PN, with epidermal hyperplasia, hypergranulosis, hyperkeratosis, and increased fibroblasts and capillaries.8,29

Pemphigoid nodularis is a rare subtype of bullous pemphigoid that exhibits characteristics of PN with pruritic plaques and erosions.8,29,33 The patient population for pemphigoid nodularis tends to be aged 50 to 60 years, and females are affected more frequently than males. However, pemphigoid nodularis may manifest with blistering and large plaques, which are not seen commonly with PN.29 On histopathology, pemphigoid nodularis deposits IgG and C3 on the basement membrane and has subepidermal clefting, unlike PN.7,29

Actinic prurigo manifests with pruritic papules or nodules post–UV exposure to unprotected skin.8,29,33 This rare condition usually manifests with cheilitis and conjunctivitis. Unlike PN, which commonly affects elderly populations, actinic prurigo typically is found in young females.8,29 Cytologic examination shows hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis with lymphocytic perivascular infiltration of the dermis.34

Neurotic excoriations also tend to mimic PN with raised excoriated lesions; however, this disorder is due to neurotic picking of the skin without associated pruritus or true hyperkeratosis.8,29,33 Histopathology shows epidermal crusting with inflammation of the upper dermis.35

Infiltrative cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may imitate PN in appearance. It manifests as tender, ulcerated, scaly plaques or nodules. Histopathology shows cytologic atypia with an infiltrative architectural pattern and presence of collections of compact keratin and parakeratin (called keratin pearls).

Keratoacanthomas can resemble PN lesions. They usually manifest as nodules measuring 1 to 2 cm in diameter and 0.5 cm thick, resembling crateriform tumors.36 On histopathology, KAs can resemble SCCs; however, KAs tend to manifest more frequently with a keratin-filled crater with a ground-glass appearance.36

Inverted follicular keratosis commonly manifests on the face in elderly men as a single, flesh-colored, verrucous papule that may resemble PN. However, cytology of inverted follicular keratosis is characterized by proliferation and squamous eddies.37 Consideration of the histologic findings and clinical appearance are important to differentiate between PN and cutaneous SCC.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is a benign condition that manifests as a plaque or nodule with crust, scale, or ulceration. Histologically, this condition presents with hyperplastic proliferation of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium.38 The clinical and histologic appearance can mimic PN and other cutaneous eruptions with epidermal hyperplasia.

In clinical cases that are resistant to treatment, biopsy is the best approach to diagnose the lesion. Due to similarities in physical appearance and superficial histologic presentation of PN, KAs from SCC, hypertrophic lichen planus, and other hyperkeratotic lesions, the biopsy should be taken at the base of the lesion to sample deeper layers of skin to differentiate these dermatologic disorders.