Characteristics

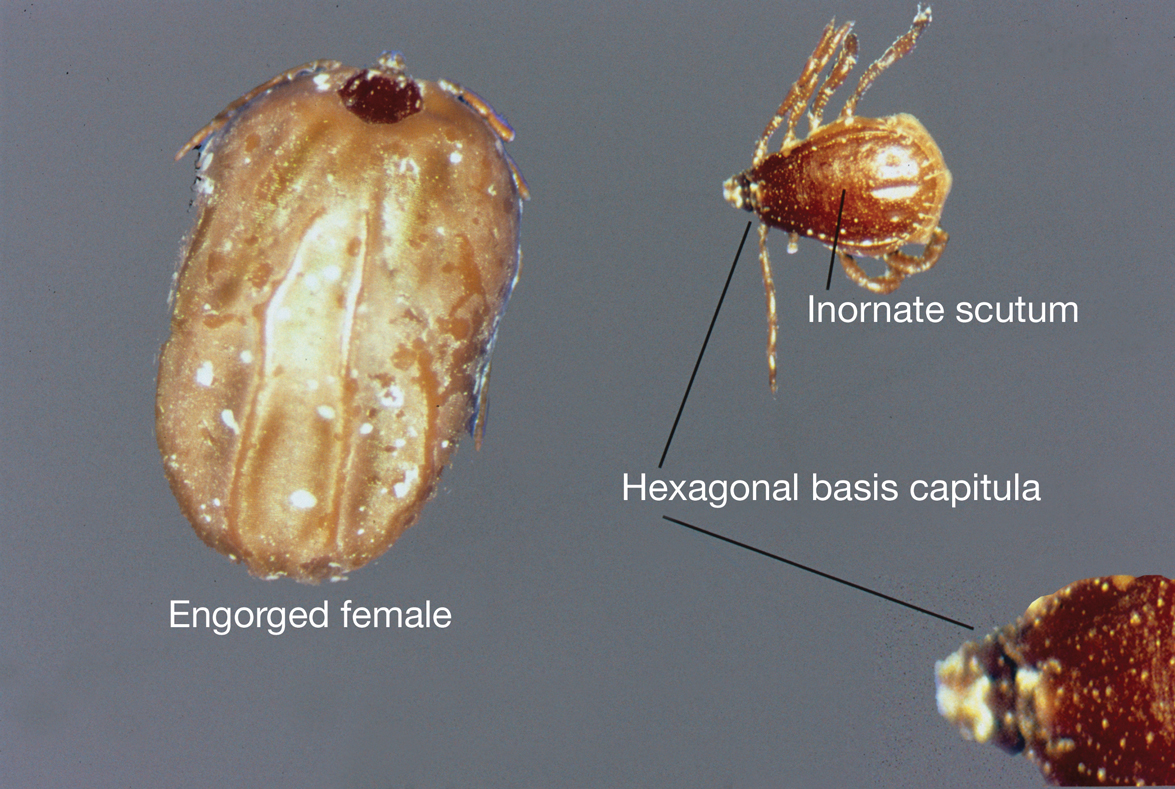

Rhipicephalus ticks belong to the Ixodidae family of hard-bodied ticks. They are large and teardrop shaped with an inornate scutum (hard dorsal plate) and relatively short mouthparts attached at a hexagonal basis capitulum (base of the head to which mouthparts are attached)(Figure).1 Widely spaced eyes and festoons also are present. The first pair of coxae—attachment base for the first pair of legs—are characteristically bifid; males have a pair of sclerotized adanal plates on the ventral surface adjacent to the anus as well as accessory adanal shields.2 Rhipicephalus (formerly Boophilus) microplus (the so-called cattle tick) is a newly added species; it lacks posterior festoons, and the anal groove is absent.3

Almost all Rhipicephalus ticks, except for R microplus, are 3-host ticks in which a single blood meal is consumed from a vertebrate host at each active life stage—larva, nymph, and adult—to complete development.4,5 In contrast to most ixodid ticks, which are exophilic (living outside of human habitation), the Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato species (the brown dog tick) is highly endophilic (adapted to indoor living) and often can be found hidden in cracks and crevices of walls in homes and peridomestic structures.6 It is predominately monotropic (all developmental stages feed on the same host species) and has a strong host preference for dogs, though it occasionally feeds on other hosts (eg, humans).7 Although most common in tropical and subtropical climates, they can be found anywhere there are dogs due to their ability to colonize indoor dwellings.8 In contrast, R microplus ticks have a predilection for cattle and livestock rather than humans, posing a notable concern to livestock worldwide. Infestation results in transmission of disease-causing pathogens, such as Babesia and Anaplasma species, which costs the cattle industry billions of dollars annually.9

Clinical Manifestations and Treatment

Tick bites usually manifest as intensely pruritic, erythematous papules at the site of tick attachment due to a local type IV hypersensitivity reaction to antigens in the tick’s saliva. This reaction can be long-lasting. In addition to pruritic papules following a bite, an attached tick can be mistaken for a skin neoplasm or nevus. Given that ticks are small, especially during the larval stage, dermoscopy may be helpful in making a diagnosis.10 Symptomatic relief usually can be achieved with topical antipruritics or oral antihistamines.

Of public health concern, brown dog ticks are important vectors of Rickettsia rickettsii (the causative organism of Rocky Mountain spotted fever [RMSF]) in the Western hemisphere, and Rickettsia conorii (the causative organism of Mediterranean spotted fever [MSF][also known as Boutonneuse fever]) in the Eastern hemisphere.11 Bites by ticks carrying rickettsial disease classically manifest with early symptoms of fever, headache, and myalgia, followed by a rash or by a localized eschar or tache noire (a black, necrotic, scabbed lesion) that represents direct endothelial invasion and vascular damage by Rickettsia.12 Rocky Mountain spotted fever and MSF are more prevalent during summer, likely due, in part, to the combination of increased outdoor activity and a higher rate of tick-questing (host-seeking) behavior in warmer climates.4,7

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever—Dermacentor variabilis is the primary vector of RMSF in the southeastern United States; Dermacentor andersoni is the major vector of RMSF in Rocky Mountain states. Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato is an important vector of RMSF in the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America.11,13

Early symptoms of RMSF are nonspecific and can include fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, and malaise. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, anorexia) may occur; notable abdominal pain occurs in some patients, particularly children. A characteristic petechial rash occurs in as many as 90% of patients, typically at the third to fifth day of illness, and classically begins on the wrists and ankles, with progression to the palms and soles before spreading centripetally to the arms, legs, and trunk.14 An eschar at the inoculation site is uncommon in RMSF; when present, it is more suggestive of MSF.15

The classic triad of fever, headache, and rash is present in 3% of patients during the first 3 days after a tick bite and in 60% to 70% within 2 weeks.16 A rash often is absent when patients first seek medical attention and may not develop (absent in 9% to 12% of cases; so-called spotless RMSF). Therefore, absence of rash should not be a reason to withhold treatment.16 Empiric treatment with doxycycline should be started promptly for all suspected cases of RMSF because of the rapid progression of disease and an increased risk for morbidity and mortality with delayed diagnosis.