To the Editor:

Reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE) is a rare self-limited cutaneous vascular proliferation of endothelial cells within blood vessels that manifests clinically as infiltrated red-blue patches and plaques with purpura that can progress to occlude vascular lumina. The etiology of RAE is mostly idiopathic; however, the disorder typically occurs in association with a range of systemic diseases, including infection, cryoglobulinemia, leukemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, peripheral vascular disease, and arteriovenous fistula. Histopathologic examination of these lesions shows marked proliferation of endothelial cells, including occlusion of the lumen of blood vessels over wide areas.

After ruling out malignancy, treatment of RAE focuses on targeting the underlying cause or disease, if any is present; 75% of reported cases occur in association with systemic disease.1 Onset can occur at any age without predilection for sex. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis commonly manifests on the extremities but may occur on the head and neck in rare instances.2

The rarity of the condition and its poorly defined clinical characteristics make it difficult to develop a treatment plan. There are no standardized treatment guidelines for the reactive form of angiomatosis. We report a case of RAE that developed 2 weeks after vaccination with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine (Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine [formerly Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson]) that improved following 2 weeks of treatment with a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine.

A 58-year-old man presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with pruritus and occasional paresthesia associated with a rash over the left arm of 1 month’s duration. The patient suspected that the rash may have formed secondary to the bite of oak mites on the arms and chest while he was carrying milled wood. Further inquiry into the patient’s history revealed that he received the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. He denied mechanical trauma. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia and a mild COVID-19 infection 8 months prior to the appearance of the rash that did not require hospitalization. He denied fever or chills during the 2 weeks following vaccination. The pruritus was minimally relieved for short periods with over-the-counter calamine lotion. The patient’s medication regimen included daily pravastatin and loratadine at the time of the initial visit. He used acetaminophen as needed for knee pain.

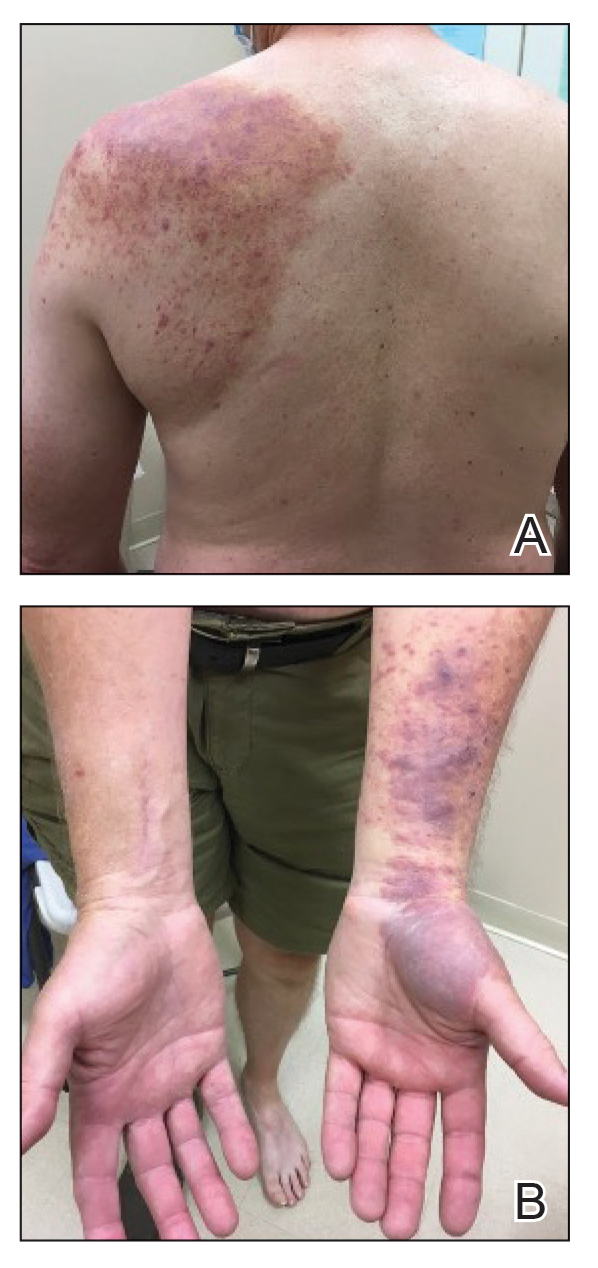

Physical examination revealed palpable purpura in a dermatomal distribution with nonpitting edema over the left scapula (Figure 1A), left anterolateral shoulder, left lateral volar forearm, and thenar eminence of the left hand (Figure 1B). Notably, the entire right arm, conjunctivae, tongue, lips, and bilateral fingernails were clear. Three 4-mm punch biopsies were performed at the initial presentation: 1 perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence testing and 2 lesional biopsies for routine histologic evaluation. An extensive serologic workup failed to reveal abnormalities. An activated partial thromboplastin time, dilute Russell viper venom time, serum protein electrophoresis, and levels of rheumatoid factor and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within reference range. Anticardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, and IgG were negative. A cryoglobulin test was negative.

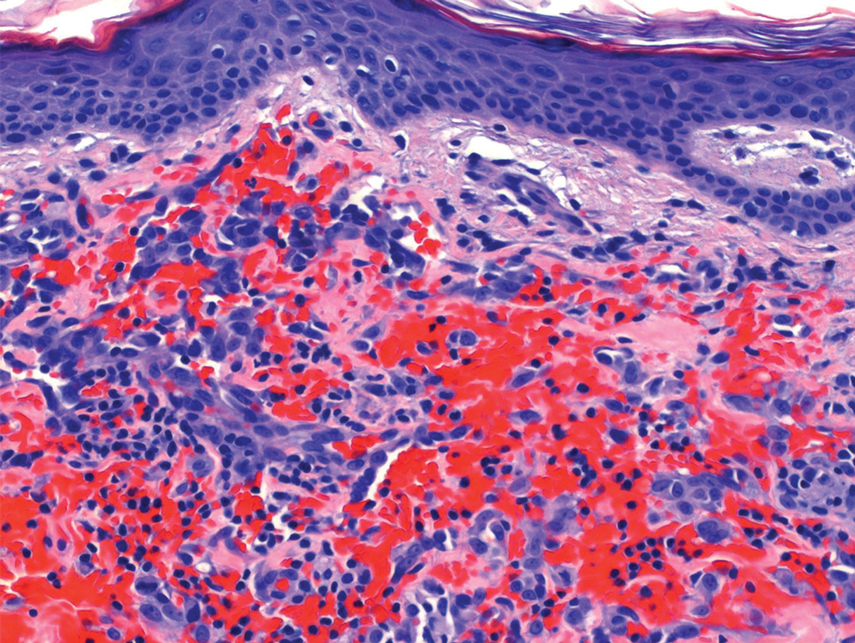

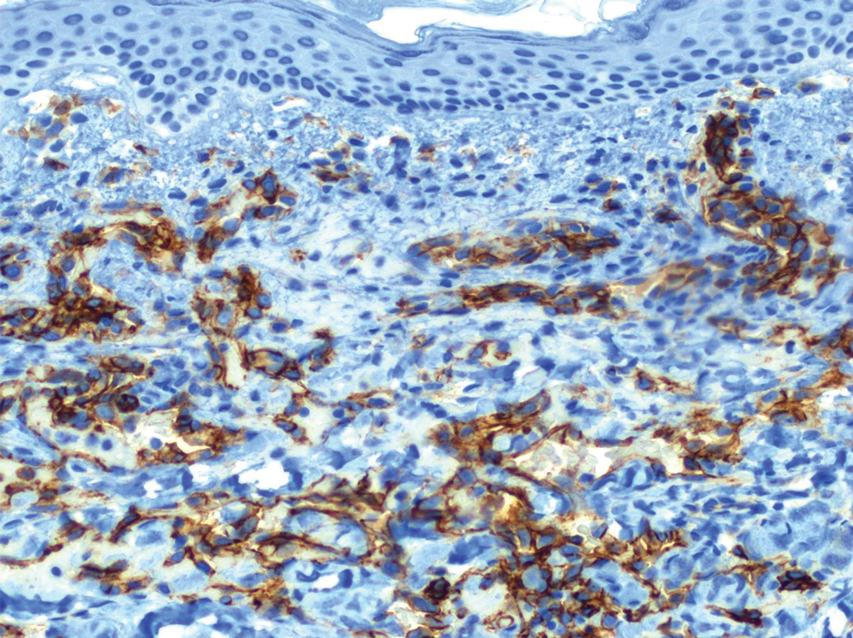

Histopathology revealed a proliferation of irregularly shaped vascular spaces with plump endothelium in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). Scattered leukocyte common antigen-positive lymphocytes were noted within lesions. The epidermis appeared normal, without evidence of spongiosis or alteration of the stratum corneum. Immunohistochemical studies of the perilesional skin biopsy revealed positivity for CD31 and D2-40 (Figure 3). Specimens were negative for CD20 and human herpesvirus 8. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional biopsy was negative.

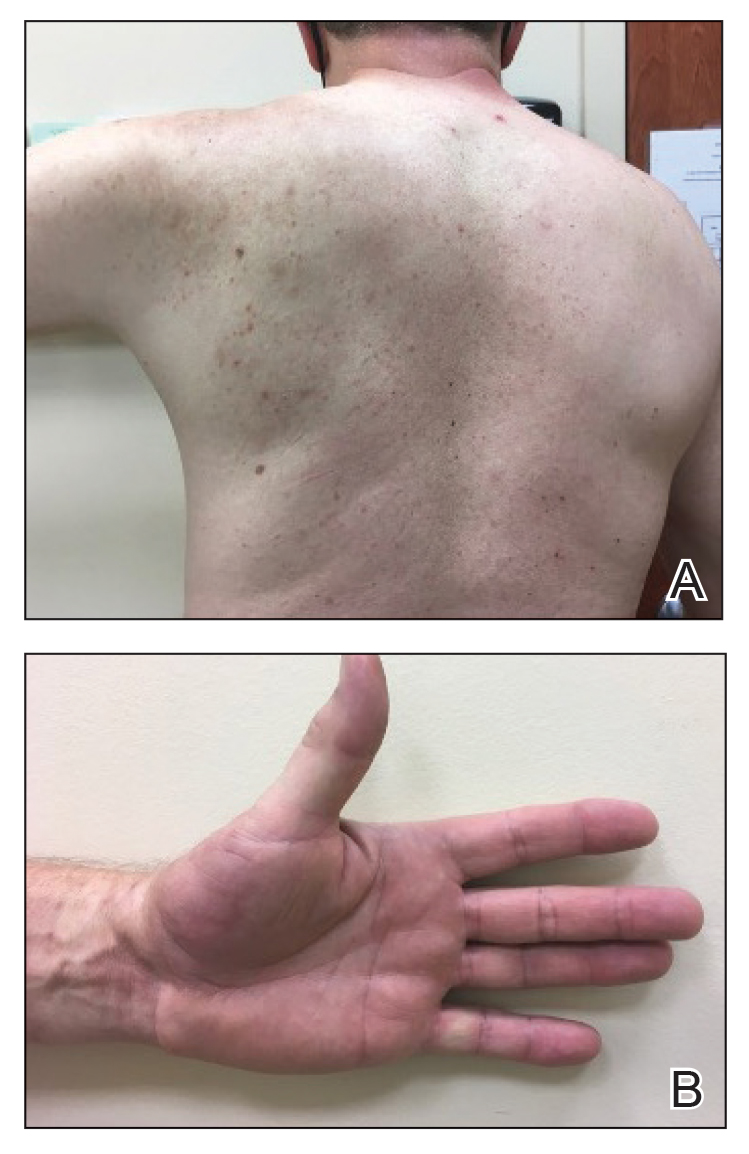

A diagnosis of RAE was made based on clinical and histologic findings. Treatment with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily and oral cetirizine 10 mg twice daily was initiated. Re-evaluation 2 weeks later revealed notable improvement in the affected areas, including decreased edema, improvement of the purpura, and absence of pruritus. The patient noted no further spread or blister formation while the active areas were being treated with the topical steroid. The treatment regimen was modified to triamcinolone ointment 0.1% once daily, and cetirizine was discontinued. At 3-month follow-up, active areas had completely resolved (Figure 4) and triamcinolone was discontinued. To date, the patient has not had recurrence of symptoms and remains healthy.