Each study design is different and your mentor should be able to help you decide which is the best to answer the question you want to ask.

In the design of a study, one of the most important principles is defining a priori end points.

Every study will have one primary end point that reflects the hypothesis. Secondary endpoints are interesting and potentially helpful, but are not the main message. It will be important to meet with a statistician before you start data collection. Understanding the statistics to be used will allow you to collect your data in the correct way (categorical vs. continuous, etc.). Reviewing charts is very time consuming and you have to do everything in your power to ensure you do it only once.

The next step is to create a research proposal. To do this, you will need to go to the literature and see what published data relate to your study. Perhaps, there are previous studies examining your question with conflicting results?

Or if your question has not been previously investigated, what supporting literature suggests that yours is the next logical study? Your proposal should include a background section (1-2 paragraphs), hypothesis (1 sentence), the specific aims of the study (1-3 sentences), methods (2-4 paragraphs), anticipated results (1 paragraph), proposed timeline, and anticipated meeting to which it will be submitted. Your mentor will revise and critique the proposal and eventually give you a signature of approval. This proposal serves many purposes. It will allow you to fully understand the study before you begin, some form of it is usually required for the Institutional Review Board application, it will serve as the outline for your eventual manuscript, and it sets a timeline for completion of the project. Without an agreed-upon deadline, too many good studies are left in various states of completion when the trainee moves on, and are never finished. The deadline should be based on the meeting that you and your mentor agree is appropriate for reporting your results.

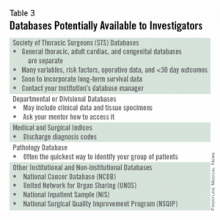

Most would agree that data collection is the most painful part of doing clinical research. However, there are a few tricks to ease your pain. First, there are many databases available that you may be able to harvest data from to minimize your chart work (Table 3). Before you hit the charts, it is essential to think through every step of the project. Anticipate problems (where in the chart will you locate each data point), do not collect unnecessary data points (postoperative data #3 serum [Na+] when looking at survival of thoracoscopic vs. open lobectomy), meet with your statistician beforehand to collect data for the correct analysis, collect the raw data (creatinine and weight, not presence of renal failure and obesity).

Finally, be sure that your data are backed up in multiple places. Some prefer to collect data on paper then enter it later into a spreadsheet. This ensures a hard copy of the data exists regardless if the electronic version is lost.

After the data are collected and the statistics are done, you will be faced with interpreting your results and composing an abstract and manuscript. If your study is focused and hypothesis driven, this step should be fairly straightforward. Schedule time with your mentor and discuss the results to ensure your interpretation of the data is correct.

Next using your proposal as an outline, put together a rough draft of a manuscript. Remember that manuscripts are the currency of academia. If you do not present and publish your work, you have not fully capitalized on the hard work you have put in to your study.

Your mentor will need to revise your manuscript repeatedly; use it as a learning experience for critiquing the literature and writing future manuscripts. He or she likely knows what editors and readers will be looking for in your finished product. Remember, you will need multiple revisions of the abstract and manuscript, so plan adequate time prior to your deadline for writing.

Most institutions have medical illustrators available for hire; consider including a drawing or photograph if it legitimately adds content to your manuscript.

The final step in the process is presenting your work in front of experts who likely know more about cardiothoracic surgery than you. Just remember, no one knows more about your data than you.

Prepare relentlessly for your talk, take a deep breath before you walk on stage, speak with confidence, and if you don't know the answer to a given question from the audience, admit it. Soon enough you will be the expert in the audience asking the tough questions. Then spend as much time as possible after the session speaking with audience members about you and your study.