"Why do I need to do research if I'm going into private practice anyway?"

I have heard this question multiple times throughout my career as a resident, fellow, and attending thoracic surgeon. The truth is, there are multiple reasons, any of which is sufficient to justify your participation in clinical research during training. First, and perhaps most importantly, it teaches you to critically appraise the literature.

This is a skill that will serve you well throughout your career, guiding your clinical decision making, regardless if you choose private practice or academic surgery.

Another reason is that performing clinical research allows you to become a content expert on a specific topic early in your career. This knowledge base is something that will serve as a foundation for ongoing learning and may help in designing future studies.

Once your project is complete, it will be your ticket to attend and present at regional, national, or international meetings. There is no better forum to gain public recognition for your investigative efforts and network with potential future partners than societal meetings.

Formal and informal interviews routinely occur at these gatherings and you do not want to be left out because you chose not to participate in research as a trainee. Finally, it is your responsibility to the patients that you have sworn to treat.

There are many ways to care for patients, and pushing back the frontiers of medical knowledge is as important as the day-to-day tasks that you perform on the ward or in the operating room.

So, now that you have decided that you want to participate in a research project as a trainee, how do you make it happen? Before you begin a project, you will have to choose a mentor; a topic; a clear, novel question; and the appropriate study design.

Chances are that at some point, a mentor helped guide you toward a career in cardiovascular surgery. A research mentor is just as important as a clinical mentor for a young surgeon. The most important trait that you should seek out in a research mentor is the ability to delineate important questions. All too often, residents and fellows are approached by attending surgeons with good intentions, but bad research ideas. Trainees then feel obligated to take them up on the project (in order to not appear like a slacker) and for various reasons, it does not result in an abstract, presentation, or publication. In fact, all it results in is frustration, a distaste for investigation, and wasted time.

The bottom line is that only you can protect your time, and as a surgical trainee, you must guard it ferociously. Look for a mentor that is an expert in your field of interest and who has a track record of publications.

He or she must be a logical thinker who can help you delineate a clear, novel question, choose the appropriate study design, guide your writing of the manuscript, and direct your submission to the appropriate meetings and journals.

Finally, your mentor must be dedicated to your success. We are all busy, but if your mentor cannot find the time to routinely meet with you at every step of your project, you need to find a new mentor.

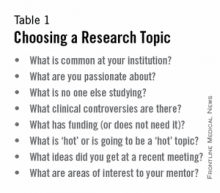

Choosing a clear, novel clinical question starts with choosing an appropriate topic (Table 1). With the right topic and question, the hypothesis is obvious, it is easy to define your endpoints, and your study design will fall into place. But with the wrong question, your study will lack focus, it will be difficult to explain the relevance of your study, and you will not want to present your data on the podium. An example of a good question is: "Do patients with a given disease treated with operation X live longer than those treated with operation Y?"

Stay away from the lure of "Let's review our experience of operation X…" or "Why don't I see how many of operation Y we've done over the past 10 years…" These topics are vague and do not ask a specific question. There must be a clear hypothesis for any study that is expected to produce meaningful results.

Once you have chosen an appropriate question, you must decide on a study design. Although case reports are marginally publishable, they will not answer your clinical questions. For many reasons, randomized, controlled trials, the gold standard of research, are difficult to design, carry out, and complete in your short time as a trainee.

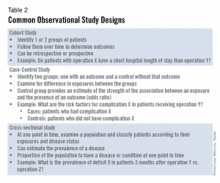

The good news is that well-designed and sufficiently powered observational studies often give similar results as randomized, controlled studies. Examples of common observational study designs include cohort studies, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies (Table 2).