Diabetes is on the rise, and so is diabetic nephropathy. In view of this epidemic, physicians should consider strategies to detect and control kidney disease in their diabetic patients.

This article will focus on kidney disease in adult-onset type 2 diabetes. Although it has different pathogenetic mechanisms than type 1 diabetes, the clinical course of the two conditions is very similar in terms of the prevalence of proteinuria after diagnosis, the progression to renal failure after the onset of proteinuria, and treatment options.1

DIABETES AND DIABETIC KIDNEY DISEASE ARE ON THE RISE

The incidence of diabetes increases with age, and with the aging of the baby boomers, its prevalence is growing dramatically. The 2005– 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated the prevalence as 3.7% in adults age 20 to 44, 13.7% at age 45 to 64, and 26.9% in people age 65 and older. The obesity epidemic is also contributing to the increase in diabetes in all age groups.

Diabetic kidney disease has increased in the United States from about 4 million cases 20 years ago to about 7 million in 2005–2008.2 Diabetes is the major cause of end-stage renal disease in the developed world, accounting for 40% to 50% of cases. Other major causes are hypertension (27%) and glomerulonephritis (13%).3

Physicians in nearly every field of medicine now care for patients with diabetic nephropathy. The classic presentation—a patient who has impaired vision, fluid retention with edema, and hypertension—is commonly seen in dialysis units and ophthalmology and cardiovascular clinics.

CLINICAL PROGRESSION

Early in the course of diabetic nephropathy, blood pressure is normal and microalbuminuria is not evident, but many patients have a high glomerular filtration rate (GFR), indicating temporarily “enhanced” renal function or hyperfiltration. The next stage is characterized by microalbuminuria, correlating with glomerular mesangial expansion: the GFR falls back into the normal range and blood pressure starts to increase. Finally, macroalbuminuria occurs, accompanied by rising blood pressure and a declining GFR, correlating with the histologic appearance of glomerulosclerosis and Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules.4

Hypertension develops in 5% of patients by 10 years after type 1 diabetes is diagnosed, 33% by 20 years, and 70% by 40 years. In contrast, 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes have high blood pressure at diagnosis.

Unfortunately, in most cases, this progression is a one-way street, so it is critical to intervene to try to slow the progression early in the course of the disease process.

SCREENING FOR DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

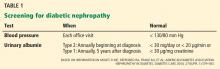

Nephropathy screening guidelines for patients with diabetes are provided in Table 1.5

Blood pressure should be monitored at each office visit (Table 1). The goal for adults with diabetes should be to reduce blood pressure to 130/80 mm Hg. Reduction beyond this level may be associated with an increased mortality rate.6 Very high blood pressure (> 180 mm Hg systolic) should be lowered slowly. Lowering blood pressure delays the progression from microalbuminuria (30–299 mg/day or 20–199 μg/min) to macroalbuminuria (> 300 mg/day or > 200 μg/min) and slows the progression to renal failure.

Urinary albumin. Proteinuria takes 5 to 10 years to develop after the onset of diabetes. Because it is possible for patients with type 2 diabetes to have had the disease for some time before being diagnosed, urinary albumin screening should be performed at diagnosis and annually thereafter. Patients with type 1 are usually diagnosed with diabetes at or near onset of disease; therefore, annual screening for urinary albumin can begin 5 years after diagnosis.5

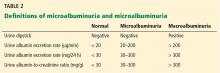

Proteinuria can be measured in different ways (Table 2). The basic screening test for clinical proteinuria is the urine dipstick, which is very sensitive to albumin and relatively insensitive to other proteins. “Trace-positive” results are common in healthy people, so proteinuria is not confirmed unless a patient has repeatedly positive results.

Microalbuminuria is important to measure, especially if it helps determine therapy. It is not detectable by the urinary dipstick, but can be measured in the following ways:

- Measurement of the albumin-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection

- 24-hour collection (creatinine should simultaneously be measured and creatinine clearance calculated)

- Timed collection (4 hours or overnight).

The first method is preferred, and any positive test result must be confirmed by repeat analyses of urinary albumin before a patient is diagnosed with microalbuminuria.

Occasionally a patient presenting with proteinuria but normal blood sugar and hemoglobin A1c will have a biopsy that reveals morphologic changes of classic diabetic nephropathy. Most such patients have a history of hyperglycemia, indicating that they actually have been diabetic.