On february 28, 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated its labeling requirements for statins. In addition to revising its recommendations for monitoring liver function and its alerts about reports of memory loss, the FDA also warned of the possibility of new-onset diabetes mellitus and worse glycemic control in patients taking statin drugs.1

This change stoked an ongoing debate about the risk of diabetes with statin use and the implications of such an effect. To understand the clinical consequences of this alert and its effect on treatment decisions, we need to consider the degree to which statins lower the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients at high risk (including diabetic patients), the magnitude of the risk of developing new diabetes while on statin therapy, and the ratio of risk to benefit in treated populations.

This review will discuss the evidence for this possible adverse effect and the implications for clinical practice.

DO STATINS CAUSE DIABETES?

Individual controlled trials dating back more than a decade have had conflicting results about new diabetes and poorer diabetic control in patients taking statins.

The West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS)2 suggested that the incidence of diabetes was 30% lower in patients taking pravastatin (Pravachol) 40 mg/day than with placebo. However, this was not observed with atorvastatin (Lipitor) 10 mg/day in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA)3 in hypertensive patients or in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS)4 in diabetic patients,4 nor was it noted with simvastatin (Zocor) 40 mg/day in the Heart Protection Study (HPS).5

The Justification for the Use of Statins in Primary Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER),6 using the more potent agent rosuvastatin (Crestor) 20 mg/day in patients with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), was stopped early when an interim analysis found a 44% lower incidence of the primary end point. However, the trial also reported a 26% higher incidence of diabetes in follow-up of less than 2 years.

In the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER),7 with a mean age at entry of 75, there was a 32% higher incidence of diabetes with pravastatin therapy.7

Results of meta-analyses

Several meta-analyses have addressed these differences.

Rajpathak et al8 performed a meta-analysis, published in 2009, of six trials—WOSCOPS,2 ASCOT-LLA,3 JUPITER,6 HPS,5 the Long-term Intervention With Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) study,9 and the Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Study in Heart Failure (CORONA),10 with a total of 57,593 patients. They calculated that the incidence of diabetes was 13% higher (an absolute difference of 0.5%) in statin recipients, which was statistically significant. In their initial analysis, the authors excluded WOSCOPS, describing it as hypothesis-generating. The relative increase in risk was less—6%—and was not statistically significant when WOSCOPS was included.

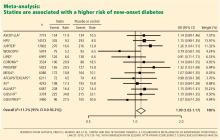

Sattar et al,11 in a larger meta-analysis published in 2010, included 91,140 participants in 13 major statin trials conducted between 1994 and 2009; each trial had more than 1,000 patients and more than 1 year of follow-up.2,3,5–7,9,10,12–17 New diabetes was defined as physician reporting of new diabetes, new diabetic medication use, or a fasting glucose greater than 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL).

New diabetes occurred in 2,226 (4.89%) of the statin recipients and in 2,052 (4.5%) of the placebo recipients, an absolute difference of 0.39%, or 9% more (odds ratio [OR] 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.17) (Figure 1).

The incidence of diabetes varied substantially among the 13 trials, with only JUPITER6 and PROSPER7 finding statistically significant increases in rates (26% and 32%, respectively). Of the other 11 trials, 4 had nonsignificant trends toward lower incidence,2,9,13,17 while the 7 others had nonsignificant trends toward higher incidence.

Does the specific statin make a difference?

Questions have been raised as to whether the type of statin used, the intensity of therapy, or the population studied contributed to these differences. Various studies suggest that factors such as using hydrophilic vs lipophilic statins (hydrophilic statins include pravastatin and rosuvastatin; lipophilic statins include atorvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin), the dose, the extent of lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and the age or clinical characteristics of the population studied may influence this relationship.18–20

Yamakawa et al18 examined the effect of atorvastatin 10 mg/day, pravastatin 10 mg/day, and pitavastatin (Livalo) 2 mg/day on glycemic control over 3 months in a retrospective analysis. Random blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels were increased in the atorvastatin group but not in the other two.18

A prospective comparison of atorvastatin 20 mg vs pitavastatin 4 mg in patients with type 2 diabetes, presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 2011 annual meeting, reported a significant increase in fasting glucose levels with atorvastatin, particularly in women, but not with pitavastatin.19

In the Compare the Effect of Rosuvastatin With Atorvastatin on Apo B/Apo A-1 Ratio in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Dyslipidaemia (CORALL) study,20 both high-dose rosuvastatin (40 mg) and high-dose atorvastatin (80 mg) were associated with significant increases in hemoglobin A1c, although the mean fasting glucose levels were not significantly different at 18 weeks of therapy.

A meta-analysis by Sattar et al11 did not find a clear difference between lipophilic statins (OR 1.10 vs placebo) and hydrophilic statins (OR 1.08). In analysis by statin type, the combined rosuvastatin trials were statistically significant in favor of a higher diabetes risk (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.44). Nonsignificant trends were noted for atorvastatin trials (OR 1.14) and simvastatin trials (OR 1.11) and less so for pravastatin (OR 1.03); the OR for lovastatin was 0.98. This may suggest that there is a stronger effect with more potent statins or with greater lowering of LDL-C.

Meta-regression analysis in this study demonstrated that diabetes risk with statins was higher in older patients but was not influenced by body mass index or by the extent that LDL-C was lowered.