Retearing after repair of the distal biceps tendon is rare.1 Heterotopic ossification (HO) is also considered uncommon, though reported rates in the literature vary widely, depending on repair and follow-up methods.1-3

In this article, we report a case of ruptured distal biceps tendon repaired with a 1-incision Endobutton technique with longitudinal clinical and imaging follow-up, and we discuss the potential biomechanical and rehabilitative implications of clinically occult retearing after repair.

This case is unique in that the patient was a physician who procured multiple magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations during the postoperative period and again at 1-year follow-up. We witnessed formation of a small focus of HO, which entered and significantly narrowed the radioulnar space on forearm pronation on dynamic MRI. There was no obvious clinical evidence for retearing; high-grade partial-thickness tendon retearing was diagnosed on MRI. This prompted a gentler rehabilitation protocol. Subsequent scar formation and tendon remodeling allowed the patient to return to full activity by 1-year follow-up, confirming recent reports that intrasubstance signal abnormalities4 and even rerupture on MRI are not correlated with symptoms.5 The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A healthy right-hand–dominant 32-year-old man was rock climbing when he heard a pop and felt sudden weakness in his right elbow. The injury occurred during eccentric contraction, while he was climbing a 45° overhanging wall with his right elbow fully extended and forearm maximally pronated. Immediately after injury, he noticed obvious deformity in the right arm. Before this incident, there was no history of elbow symptoms or any medication use.

Physical examination revealed distortion of the biceps with a palpable defect in the right elbow consistent with a complete biceps tendon rupture. This was confirmed on MRI, which showed avulsion of the distal biceps tendon from its insertion on the radius. There was 4 cm of proximal retraction of the tendon, which was kept at the level of the joint line by a partially intact lacertus fibrosis (Figure 1).

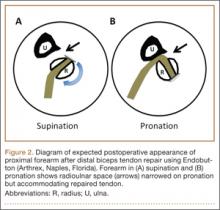

As the patient was physically active, operative treatment was chosen with the expectation of restoration to full function and strength. Six days after injury, surgery was performed using a 1-incision anterior approach with an Endobutton technique, as first described by Bain and colleagues6 and subsequently detailed by other authors.7 The diameter of the distal biceps tendon after attachment to the Endobutton (Arthrex, Naples, Florida) was measured, and a corresponding 7-mm unicortical tunnel was drilled into the radial tuberosity. During surgery, there was full range of motion (ROM) at the elbow and forearm. Before closure, the wound was copiously irrigated to minimize the potential of HO. In our practice, we do not routinely administer prophylactic anti-inflammatory drugs to low-risk patients because of the theoretical risks for delayed tendon–bone healing8 and inferior healing strength.9 The theoretical, expected postoperative appearance is illustrated in Figure 2.

For 7 days after surgery, the patient wore a posterior elbow splint in a flexed, supinated position. Afterward, rehabilitation initially consisted of passive ROM progressing to active ROM at postoperative week 4. Pronation was slow to return, but essentially full ROM was regained by 7 weeks after surgery. Seven weeks after surgery, a radiograph showed a small amount of HO near the radial tuberosity (Figure 3A). However, the patient was clinically progressing well, and by 9 weeks was comfortably performing slow, controlled arm curls with a 10-lb weight. Despite the clinical improvements, MRI 9 weeks after surgery showed high-grade partial-thickness retearing of the distal biceps tendon without significant retraction. With dynamic MRI, it was evident that the focus of HO near but external to the distal tendon entered the radioulnar space on pronation (Figures 3B–3D). On axial images of the center of the cortical tunnel, the short-axis diameter of the heterotopic bone measured 2.5 mm, and the bone clearly was occupying part of the radioulnar space during pronation. As the patient was not having pain and was increasing in strength, the clinical team resumed rehabilitation, albeit at a gentler pace.

By 1-year follow-up, the patient had returned to preinjury activity levels, which included rock climbing and weightlifting without pain or loss of strength. One year after surgery, radiographs and MRI showed maturation of heterotopic bone, which was incorporated with scar tissue along the remodeled distal biceps tendon remnant (Figures 4A-4C).

Discussion

Distal biceps tendon ruptures historically have been considered relatively rare injuries. Postrepair complications are uncommon but well known. HO has been described with all distal biceps tendon repair techniques, but rates vary depending on follow-up method. Given the data reported, HO is thought to have a higher incidence with the 2-incision technique than with the 1-incision technique.10 The literature includes fewer reports of HO with the Endobutton technique11,12 than with the suture anchor technique.3 Incidence of HO after distal biceps tendon repair has been reported to be as high as 50%, with Marnitz and colleagues5 suggesting that its presence does not necessarily affect clinical outcome. This was confirmed in our patient’s case.