MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a chart review of all patients operated on between January 2010 and March 2012 by the same surgeon. We recruited 15 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with ulnar nerve transposition for moderate to severe cubital tunnel syndrome through EMG/NCS and physical examination during this time frame. Operative reports were then reviewed. In 14 of these 15 cases, Osborne’s ligament was used as a ligamentofascial or ligamentodermal sling. In the fifteenth patient, preoperative subluxation of the ulnar nerve was identified with movement of elbow, and Osborne’s ligament was found to not be large enough to provide an appropriate sling. Three patients were unreachable, and 1 patient chose to not participate in the study. Of the initial 15 patients, 10 were given a telephone survey (Appendix A), which was prepared based on the recommendation of Novak and colleagues13 and incorporated with questions regarding preoperative symptoms, satisfaction, smoking history, and employment status. This study was Institutional Review Board approved at our institution, and appropriate consent was obtained from the participants.

Appendix A. Ulnar Nerve Telephone Survey

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

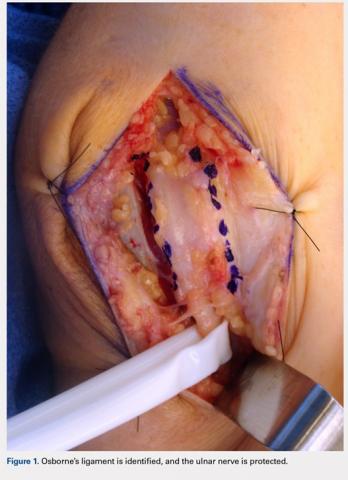

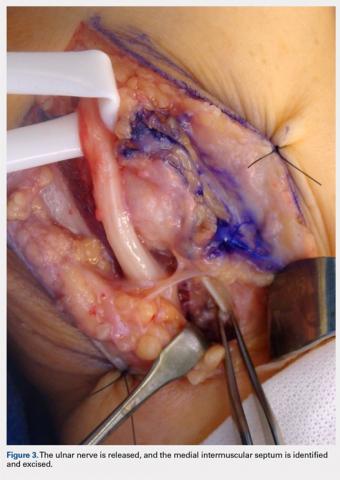

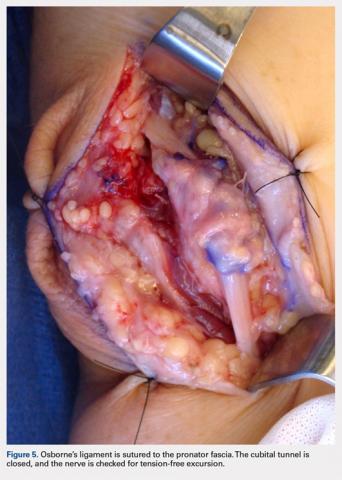

A 10 to 12 cm incision centered over the cubital tunnel is made. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is identified and protected. After dissection through superficial fascia, Osborne’s ligament is identified. The ligament is then released posteriorly from the olecranon and is assessed. The ulnar nerve is then freed in a proximal to distal manner to preserve vascular structures that supply the epineurium. The medial intermuscular septum is examined and excised as a site of compression. The ulnar nerve is then mobilized. Once mobilized, the ulnar nerve is transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle and checked to ensure that no sharp curves are made and nothing is impinging on the nerve while passively flexing and extending the elbow. The Osborne’s ligament is then passed over the top of the previously transposed ulnar nerve to create a sling that is ligamentofascial if sutured to the flexor/pronator fascia or ligamentodermal if sutured to dermis. Importantly, the flexor/pronator fascia is not incised. The remaining soft tissue and fascia of the cubital tunnel are then closed with 2-0 vicryl suture. The free end of the Osborne’s ligament is sutured to flexor/pronator fascia or to dermis, anterior to the medial epicondyle with No. 0 vicryl suture. This process is conducted in a tension-free manner to prevent creating a new site of compression. The nerve is then rechecked for appropriate, tension-free gliding followed by closure of the wound in layers after irrigation (additional details are shown in Figures 1-5).

RESULTS

Ten of the 15 patients were available for telephone review. The results of the telephone survey are as follows. The average time to telephone survey was 15.6 months (range, 4-28 months). The average time to become subjectively “better” was 4.2 weeks (range, 2-6 weeks). The average time back to work was 1.6 weeks (range, 1 day to 3 weeks). Three patients were retired and did not go back to work. All patients stated they were subjectively “better” after surgery, and when asked, all patients stated that they would choose surgery again. The average pain prior to surgery was 7.5 (range, 5.5-9.5) on a 10-point scale. The average pain after surgery at final phone interview was 0.1 on a 10-point scale (range, 0-1). All patients stated that their sensation was subjectively better after the surgery. One patient said that his strength worsened, another patient said that his strength was the same, and the remaining patients said that their strength was better. One patient was a smoker, and no patients had acute traumatic injuries that caused their ulnar nerve symptoms.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...