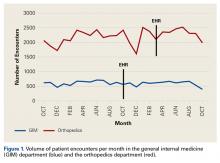

In the GIM department, mean monthly volume of patient visits in the 12 months before EHR implementation was similar to that in the 12 months afterward (613 vs 587; P = .439). Even when normalized for changes in provider availability (maternity leave), the decrease in volume of patient visits after EHR implementation in the GIM department was not significant (6.9%; P = .107). Likewise, in the orthopedics department, mean monthly volume of patient visits in the 17 months before EHR implementation was similar to that in the 7 months afterward (2157 vs 2317; P = .156). In fact, patient volumes remained constant during the EHR transition (Figure 1).

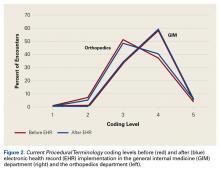

EHR implementation brought small changes in billing coding levels. In the GIM department, the largest change was a 1.2% increase in level 4 billing coding—an increase accompanied by a 0.5% decrease in level 3 coding.

In the orthopedics department, the largest change was a 3.3% increase in level 4 coding—accompanied by a 3.1% decrease in level 3 coding (Figure 2). In both departments, these small changes across all levels represent minor but statistically significant shifts in billing coding levels (Pearson χ2, P < .001) (Table).Discussion

It is remarkable that the volumes of patient visits in the GIM and orthopedics departments at our academic center were not affected by EHR implementation.

Some EHR vendors have recommended decreasing patient scheduling by 10%, for 1 month after the transition, to adjust for providers’ learning curves; managers of an academic pediatric primary care center reported maintaining the 10% scheduling reduction for 3 months because of the prevalence of inconsistent EHR users in continuity clinics and transient users such as medical students and interns.13Rather than reduce scheduling during the EHR transition, surgeons in our practice either added or lengthened clinic sessions, and the level of ancillary staffing was adjusted accordingly. As staffing costs at any given time are multifactorial and vary widely, estimating the cost of these staffing changes during the EHR transition is difficult. We should note that extending ancillary staff hours during the transition very likely increased costs, and it is unclear whether they were higher or lower than the costs that would have been incurred had we reduced scheduling or tried some combination of these strategies.

Although billing coding levels changed with EHR implementation, the changes were small. In the GIM department, level 4 CPT coded visits as percentages of all visits increased to 59.5% from 58.3%, and level 5 visits increased to 6.2% from 6.0%; in the orthopedics department, level 4 visits increased to 40.2% from 37.1%, and level 5 visits increased to 5.5% from 3.8% (Table). The 1.2% and 0.2% absolute increases in level 4 and level 5 visits in the GIM department represent 2.1% and 3.3% relative increases in level 4 and level 5 visits, and the 3.3% and 1.7% absolute increases in the orthopedics department represent 8.4% and 44.7% relative increases in level 4 and level 5 visits after EHR implementation.

Although the absolute increases in level 4 and level 5 visits were relatively minor, popular media have raised the alarm about 43% and 82% relative increases in level 5 visits after EHR implementation in some hospitals’ EDs.4 Although our orthopedics department showed a 44.7% relative increase in level 5 visits after EHR implementation, this represented an increase of only 1.7% of patient visits overall. Our findings therefore indicate that lay media reports could be misleading. Nevertheless, the small changes we found were statistically significant.

One explanation for these small changes is that EHRs facilitate better documentation of services provided. Therefore, what seem to be billing coding changes could be more accurate reports of high-level care that is the same as before. In addition, because of meaningful use mandates that coincided with the requirement to implement EHRs, additional data elements are now being consistently collected and reviewed (these may not necessarily have been collected and reviewed before). In some patient encounters, these additional data elements may have contributed to higher levels of service, and this effect could be especially apparent in EDs.

Some have suggested a potential for large-scale up-coding during EHR transitions. Others have contended that coding level increases are a consequence of a time-intensive data entry process, collection and review of additional data, and more accurate reporting of services already being provided. We are not convinced that large coding changes are attributable solely to EHR implementation, as the changes at our center have been relatively small.

Nevertheless, minor coding level changes could translate to large changes in healthcare costs when scaled nationally. Although causes may be innocuous, any increases in national healthcare costs are concerning in our time of limited budgets and scrutinized healthcare utilization.

This study had its limitations. First, including billing data from only 2 departments at a single center may limit the generalizability of findings. However, we specifically selected a GIM department and a specialty (orthopedics) department in an attempt to capture a representative sample of practices. Another limitation is that we investigated billing codes over only 2 years, around the implementation of EHRs in these departments, and therefore may have captured only short-term changes. However, as patient volumes and billing are subject to many factors, including staffing changes (eg, new partners, new hires, retirements, other departures), we attempted to limit the effect of confounding variables by limiting the period of analysis.

Overall, changes in patient volume and coded level of service during EHR implementation at our institution were relatively small. Although the trend toward higher billing coding levels was statistically significant, these 0.2% and 1.7% increases in level 5 coding hardly deserve the negative attention from lay media. These small increases are unlikely caused by intentional up-coding, and more likely reflect better documentation of an already high level of care. We hope these findings allay the concern that up-coding increased dramatically with EHR implementation.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E172-E176. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.