Amount of opioid analgesic consumed was converted into morphine equivalents to adjust for the different opioids prescribed after surgery: oxycodone/acetaminophen or oxycodone equivalent, hydrocodone/acetaminophen or hydrocodone equivalent, and acetaminophen/codeine.

Patients were excluded from the study if their procedure was performed on an inpatient basis, if they sustained other injuries or fractures from their trauma, or if an adjunctive procedure (including carpal tunnel release) was performed during the DRF repair.

We used the Spearman rank correlation coefficient and a count data model to examine the relationship between opioid use and age. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine the relationships between opioid use and payer type, anesthesia type, and fracture type.

Results

Of the 109 patients eligible for the study, 11 were excluded for incomplete postoperative questionnaires, leaving 98 patients (79 females, 19 males) for analysis. Mean age was 58 years (range, 13-92 years). Of the 98 patients, 45 received general anesthesia, and 53 received regional anesthesia with a single-shot peripheral nerve block before surgery and sedation perioperatively (Table).

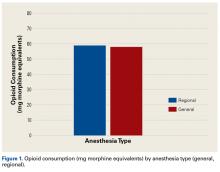

A single-shot supraclavicular nerve block (30 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine plus 5 mg of dexamethasone) was administered by a board-certified anesthesiologist. Mean opioid consumption (morphine equivalents) was 58.5 mg (range, 0-280 mg), roughly equivalent to 14.6 tabs of oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg. Sixty-seven patients (68.4%) consumed <75 mg of morphine equivalents, or <20 tabs of oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg. Mean duration of use was 4.8 days (range, 0-16 days) after surgery. There were no significant differences (P = .74) in opioid consumption between patients who received general anesthesia and patients who received regional anesthesia (Figure 1).Of the 98 study patients, 61 reported using over-the-counter adjunctive pain medications during the postoperative period, and 37 reported no use. Mean opioid consumption was 64.7 mg of morphine equivalents for the adjunctive medication users and 48.3 mg for the nonusers (P = .1947).

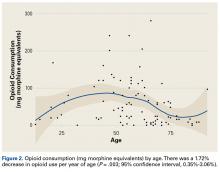

Demographic analysis revealed an inverse relationship between age and opioid use (Figure 2). The Spearman ρ between age and opioid consumption was –0.2958, which suggests decreased opioid use by older patients (P = .003).

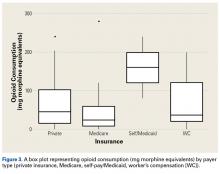

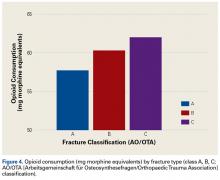

A count data model with negative binomial distribution suggested opioid consumption decreased by 1.72% per year of age (95% confidence interval, 0.35%-3.06%). Similarly, a relationship was found between opioid consumption and payer type (Figure 3), with consumption highest for self-pay and Medicaid patients (P = .063). However, this finding should be interpreted carefully, as it was underpowered—there were only 3 patients in the self-pay/Medicaid group.All fractures were graded with the AO/OTA long-bone fracture classification system. Mean opioid consumption for the 3 fracture-type groups was 57.7 mg (class A), 60.3 mg (class B), and 62.0 mg (class C) (Figure 4).

Although the data demonstrate a trend toward increasing opioid consumption in patients who underwent fixation of complete intra-articular DRFs, as opposed to partial articular and extra-articular fractures, the difference was not significant (P = .99).Discussion

The US healthcare culture has elevated physicians’ responsibility in adequately and aggressively managing their patients’ pain experience. Moreover, reimbursement may be affected by patient satisfaction scores, which are partly predicated on pain control.20-24 However, as rates of opioid use and abuse rise, it is important that physicians prescribe such medications judiciously. This is particularly germane to orthopedic surgeons, who prescribe more opioid analgesics than surgeons in any other field.17 Rodgers and colleagues18 found upper extremity surgeons, in particular, tended to overprescribe postoperative opioid analgesics. In the present study, we sought to identify the crucial risk factors that influence post-DRF-ORIF pain management and opioid consumption.

Mean postoperative opioid consumption (morphine equivalents) was 58.5 mg, roughly equivalent to 14.6 tabs of oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg, an opioid analgesic commonly used during the acute postoperative period. In addition, almost 70% of our patients required <75 mg of morphine equivalents, or <20 tabs of oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg. For upper extremity surgeons, these numbers may be better guides in determining the most appropriate amount of opioid to prescribe after DRF repair.

As for predicting levels of postoperative opioid medication, there was a significant trend toward less consumption with increasing age. Given this finding, surgeons prescribing for elderly patients should expect less opioid use. Regarding payer type, there was a trend toward more opioid use by self-pay/Medicaid patients; however, there were only 3 patients in this group. The situation in the study by Rodgers and colleagues18 is similar: Their finding that Medicaid patients consumed more pain pills after surgery was underpowered (only 5 patients in the group).

In the orthopedic community, support for use of regional anesthesia has been widespread for several reasons, including the belief that it reduces postoperative pain and therefore should reduce postoperative opioid consumption.25 However, we found no significant difference in postoperative opioid consumption between patients who received general anesthesia (with and without local anesthesia) and patients who received regional anesthesia (nerve block). Mean opioid consumption was 57.93 mg in the general anesthesia group and 58.98 mg in the regional anesthesia group. However, this finding could have been confounded by the variability in success and operator dependence inherent in regional anesthesia. In addition, the anatomical location for the peripheral nerve block and anesthetic could have affected the efficacy of the block and played a role in postoperative opioid consumption.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that there would be more postoperative opioid consumption with worsening fracture type. Although our results did not reach statistical significance, there was a trend toward increased opioid consumption in patients with a complete intra-articular fracture (AO/OTA class C) vs patients with a partial articular fracture (class B) or an extra-articular fracture (class A). In addition, patients with a partial articular fracture tended to use more postoperative opioids than patients with an extra-articular fracture. In short, postoperative opioid consumption tended to be higher with increasing articular involvement of the fracture.

This study was limited in that it relied on patient self-reporting. Given the social stigma attached to opioid use, patients may have underreported their postoperative opioid consumption, been affected by recall bias, or both. The study also did not control for preoperative opioid use or history of opioid or substance abuse. Chronic preoperative opioid consumption may have affected postoperative opioid use. Other patient-related factors, such as body mass index (BMI) and hepatorenal dysfunction, can create tremendous variability in opioid metabolism across a population. Such factors were not controlled for in this study and therefore may have affected its results. That could help explain why older patients, who are more likely to have lower BMI and less efficient organ function for opioid metabolism, had lower postoperative opioid consumption. In addition, although we excluded patients with concomitant injuries and procedures, we did not screen patients for concomitant complex regional pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, or other medical conditions that might have had a significant impact on postoperative pain management needs. Last, some findings, such as the relationship between opioid use and payer type, were underpowered: Although self-pay/Medicaid patients had higher postoperative opioid consumption, they were few in number. The same was true of the Medicaid patients in the study by Rodgers and colleagues.18Our results demonstrated that post-DRF-ORIF opioid consumption decreased with age and was independent of type of perioperative anesthesia. There was a trend toward more opioid consumption with both self- and Medicaid payment and worsening fracture classification. It has become more important than ever for orthopedic surgeons to adequately manage postoperative pain while limiting opioid availability and the risk for abuse. Surgeons must remain aware of the variables in their patients’ postoperative pain experience in order to better optimize prescribing patterns and provide a safe and effective postoperative pain regimen.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E35-E40. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.