Results

Over the 2000–2012 period, 1507 students from our institution successfully applied to residency programs: 792 in the precurriculum group and 715 in the postcurriculum group. Of these students, 91 successfully applied to orthopedic surgery: 48 in the precurriculum group (applied before introduction of the required clerkship) and 43 in the postcurriculum group (applied afterward).

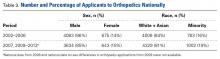

Each cohort represented 6% of the total number of students. Table 2 lists the groups’ demographics.Over the 2002–2012 period, 10,100 US allopathic medical students applied to orthopedic residency programs: 4769 students between 2002 and 2006 and 5331 students between 2007 and 2012.

Table 3 lists these groups’ demographics.Before the musculoskeletal clerkship was required, 317 (40%) of the 792 precurriculum students were exposed to orthopedics during their third year. During this period, 42 of the 48 orthopedic surgery applicants completed an orthopedic surgery rotation during their third year of medical school. After the clerkship was required, 465 (65%) of the 715 postcurriculum students were exposed to orthopedics during their third year, including all 43 orthopedic surgery applicants (100% of students were exposed to musculoskeletal surgery, including plastic surgery and neurologic spine). The 25% increase in exposure to orthopedic surgery during the third year was statistically significant (P < .0001), but there was no resultant increase in overall percentage of students applying to orthopedic residencies (6% in each case; P = .98).

Over the 12-year study period, the proportion of female medical students at our institution declined from 50% (395/792) to 46% (328/715) (P = .13). However, there was an 81% relative increase, from 17% (8/48) before introduction of the clerkship to 30% (13/43) afterward, in the proportion of female applicants to orthopedic surgery. This contrasted with national data showing the percentage of female applicants to orthopedic surgery remained stable from 2002–2006 (14%, 675/4758) to 2007–2012 (15%, 643/4277). Before the clerkship was required, the proportion of female applicants from our institution was similar to national rates (P = .50). Afterward, our institution produced a significantly higher proportion of female applicants compared with the national proportion (P = .026).

Over the 12-year period, our self-identified underrepresented minority medical student population increased significantly (P = .02), from 13% (103/792) to 17% (124/715). The relative proportion of underrepresented minority orthopedic surgery applicants increased by 101%, from 10% (5/48) before the clerkship was required to 21% (9/43) afterward. Nationally, over the same period, underrepresented minorities’ orthopedic surgery application rates increased significantly (P < .001), from 16% (763/4769) to 19% (1002/5331). The proportion of underrepresented racial minorities that applied did not differ significantly between our institution and nationally for the years either before (P = .97) or after (P = .68) introduction of the curriculum.

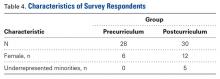

Surveys were completed by 58 (64%) of 91 graduates (21 women, 70 men). Respondents’ characteristics are listed in Table 4.

Eighteen (86%) of the 21 female graduates completed the survey: 6 (75%) of 8 precurriculum and 12 (92%) of 13 postcurriculum. Only 5 (36%) of 14 underrepresented minorities completed the survey, all postcurriculum. Of the 28 precurriculum respondents, 22 (79%) decided to apply to orthopedic surgery during their third or fourth year, and this was true for 25 (83%) of 30 postcurriculum respondents. Of all 58 respondents, 51 (88%) indicated that their third-year rotation in musculoskeletal medicine influenced their choice of specialty. Specifically, 3 precurriculum respondents (1 female) had no interest in orthopedic surgery until their third-year experience. By contrast, 7 postcurriculum students (5 females/minorities) had no prior interest in orthopedics—they chose to pursue the specialty after their orthopedic rotation.Discussion

Orthopedic surgery needs a more diverse workforce11-17 in order to better mirror the population served, bring care to underserved areas,18-26 and provide better training environments.27 Several hypotheses about the lack of diversity have been posited: stereotypes about the specialty,28-31 lack of interest among minority medical students, and lack of exposure to the specialty.5,6,32,33

Lack of exposure deserves scrutiny, as a large proportion of medical students who choose to apply to orthopedic surgery make their decision before entering medical school, which is not typical.33 Such a finding suggests that exposure to orthopedic surgery is lacking, especially given that an orthopedic surgery rotation is usually not required during the clinical years. The idea that increased exposure to orthopedics affects application patterns is logical, as clinical exposure has been shown to play a role in medical students’ choice of specialty.34

Exposure helps in several key areas. Firsthand experience can help dispel stereotypes, such as the idea that success in orthopedic surgery depends on physical strength and that only former athletes pursue orthopedics.28-31 Authors have also reported on a perceived negative bias against women: Orthopedics is an “old boys’ network”; women will not fit in and need not apply; the orthopedic lifestyle is difficult and not conducive to a satisfying personal life.9 Requiring exposure ensures that all students, but especially women, can gain firsthand experience that can show these stereotypes to be false. Beyond dispelling these stereotypes, exposure to orthopedic surgery is essential for women, as studies have shown that clinical rotations play a larger role in determining specialty choice for women compared to men,33 and this would be particularly critical for specialties they may not be initially considering.

A national study found that requiring an orthopedic/musculoskeletal clerkship led to a 12% relative increase in the application rate, from 5.1% to 5.7%, and to an increase in applicant diversity (race, sex).10 However, the investigators could not determine individual reasons for specialty choice or the exact nature of each institution’s musculoskeletal curriculum. Confirming these factors, we found an 81% increase in number of female applicants and a 101% increase in number of underrepresented minority applicants after introduction of the required third-year musculoskeletal surgery clerkship at our institution.

We were unable to replicate the 12% relative increase in the overall application rate; our orthopedic surgery match rate remained 6%. Our findings cannot directly explain this, but we have several hypotheses. First, whereas other studies measured the application rate, we measured the successful match rate, given our data structure. This difference in data definition could account for some of the discrepancy. Second, we did not account for individuals’ academic success, and career counseling is paramount in decisions regarding residency specialties. It is possible we are substituting qualified female and underrepresented minority candidates for less-than-qualified male applicants. Third, the 25% increase in medical student exposure to orthopedic surgery led to a corresponding increase in number of orthopedic faculty providing undergraduate medical education. Some of these faculty could have been inexperienced in undergraduate medical education, and thus the teaching environment may not have been optimal.

Our study had several limitations. First, our institution has limited racial diversity. Over the past 12 years, only 15% of our students have been underrepresented minorities. (Nationally, the proportion is closer to 18%.) This may have limited the ability of our orthopedic rotation to affect the proportion of underrepresented minority applicants. Second, this study involved medical students at only one institution, which limits generalizability of findings. Third, we were unable to obtain records specifying which faculty and residents interacted with which medical students, and the increased number of female faculty and residents coinciding with the curriculum change may also be a factor. However, we expect that, without the curriculum change, these students would have had smaller odds of interacting with these potential female role models in orthopedics, negating any affect they may have had. Last, although we contacted former students to ask about their reasons for choosing the orthopedics residency, those findings are limited by a potential respondent selection bias.

The qualities and characteristics of successful orthopedic surgeons, as presented in both medical and lay cultures, are subject to numerous stereotypes. By increasing medical student exposure to orthopedics during the third year of medical school, we are giving a larger proportion of our students direct clinical experience in a field they may not have been considering. This exposure allows students to interact with mentors who can be positive role models—orthopedic surgeons who are dispelling stereotypes. By increasing medical student exposure and reaching students who may not have been considering orthopedics, we have increased diversity among our applicants. Third-year medical students’ exposure to orthopedic surgery is essential in promoting a more diverse workforce.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E347-E351. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.