Lisfranc Injuries

Lisfranc injuries include any bony or ligamentous damage that involves the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joints. While axial loading of a fixed, plantarflexed foot has traditionally been thought of as the most common mechanism of Lisfranc injury, we have found that noncontact twisting injuries leading to Lisfranc disruption are actually more common among NFL players. This mechanism is similar to noncontact turf toe and results in a purely ligamentous injury. We have found this to be particularly true in the case of defensive ends engaged with offensive linemen in which no axial loading or contact of the foot occurs. Clinically, patients often have painful weight-bearing, inability to perform a single limb heel rise, plantar ecchymosis, and swelling and point tenderness across the bases of the 1st and 2nd metatarsals.

It is critical to obtain comparison weight-bearing radiographs of both feet during initial work-up to look for evidence of instability. Subtle radiographic findings of Lisfranc injury include a bony “fleck” sign, compression fracture of the cuboid, and diastasis between the base of the 1st and 2nd metatarsals and/or medial and middle cuneiforms (Figures 3A, 3B).

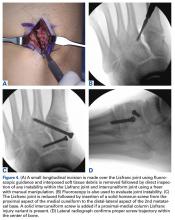

Stress testing involves pronation and adduction of the foot under live fluoroscopy to evaluate for diastasis. MRI can be helpful in cases of vague pain with negative radiographs and subtle displacement. Nonoperative treatment for cases of no instability or displacement involved protected weight-bearing for 4 weeks followed by progressive increase in activities, with RTP 6 to 8 weeks after injury.The goal of surgical intervention is to obtain and maintain anatomic reduction of all unstable joints in order to restore a normal foot posture. One of the difficulties with Lisfranc injuries is that there are no exact diastasis parameters and individuals should be treated based on symptoms, functional needs, and degree of instability. It has been shown that 5 mm of displacement can have good long-term clinical results in select cases without surgery.18 For surgery, we recommend open reduction to remove interposed soft tissue debris and directly assess the articular surfaces (Figures 4A-4D).

A freer can be placed in the individual joints to assess for areas of instability. We prefer solid screw fixation (Charlotte Lisfranc Reconstruction System, Wright Medical Technology) to decrease the risk of later screw breakage. A homerun screw from the proximal aspect of the medial cuneiform to the distal-lateral aspect of the 2nd metatarsal base should be placed first. Bridge plates can be used over the 1st and 2nd TMT joints to avoid articular cartilage damage without a loss of rigidity.19Proximal-medial column Lisfranc injury variants are increasingly common among football players.20 In these injuries, the force of injury extends through the intercuneiform joint and exits out the naviculocuneiform joint, thus causing instability at multiple joints and an unstable 1st ray. Patients often have minimal clinical findings and normal radiographs and stress radiographs. MRI of the foot often reveals edema at the naviculocuneiform joint. Often patients fail to improve with nonoperative immobilization with continued inability to push off from the hallux. Unrecognized or untreated instability will lead to rapid deterioration of the naviculocuneiform joint. Surgical intervention requires a homerun screw and intercuneiform screw. We do not recommend primary arthrodesis in athletes due to significant risk of malunion and nonunion unless severe articular damage is present.

Patients are typically kept NWB in a splint for 2 weeks after surgery followed by NWB in a tall CAM from 3 to 4 weeks postoperative. Progressive weight-bearing and ROM exercises are initiated from 4 to 8 weeks, followed by return to accommodative shoe wear from 10 to 12 weeks. Hardware removal is performed 4 to 6 months after surgery, typically in the off-season to allow for 6 to 8 weeks or protected recovery afterwards. Premature hardware removal can lead to loss of reduction, particularly at the intercuneiform joints. All hardware crossing the TMT joints should be removed, while the homerun screw can be left in place in addition to the intercuneiform screw. RTP in football typically occurs 6 to 7 months after surgery. Final functional outcome is related to the adequacy of initial reduction and severity of the initial injury.21

Syndesmotic Disruption

Syndesmotic injuries comprise 1% to 18% of ankle sprains in the general population, but occur at much higher rates in football due to the increased rotation forces placed on the ankle during cutting and tackling. RTP after syndesmotic injury often takes twice as long when compared to isolated lateral ankle ligamentous injury.22 Missed injuries are common and if not treated properly can lead to chronic ankle instability and posttraumatic ankle arthritis.23 Syndesmotic injury can occur in isolation or with concomitant adjacent bony, cartilaginous, or ligamentous injuries. Therefore, clinical examination and imaging work-up are critical to successful management.