Pre-Participation Examination. The purpose of the pre-participation examination (PPE) is to maximize an athlete’s safety by identifying medical conditions that place the athlete at risk.11,12 The Preparticipation Physical Evaluation, 4th edition, the most widely used consensus publication, specifically queries if an athlete has a previous history of heat injury. However, it only indirectly addresses intrinsic risk factors that may predispose an athlete to EHI who has never had an EHI before. Therefore, providers should take the opportunity of the PPE to inquire about additional risk factors that may make an athlete high risk for sustaining a heat injury. Common risk factors for EHI are listed in Table 1.

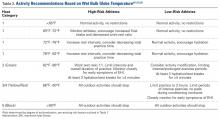

While identifying at-risk athletes is important in mitigating the risk of developing EHI, it will not identify all possible cases: a study of military recruits found that up to 50% of Marines who developed EHI lacked an identifiable risk factor.13Wet Bulb Globe Temperature. Humidity can heighten a player’s risk of developing thermogenic dysregulation during hot temperatures. As ambient temperature nears internal body temperature, heat may actually be absorbed by the skin rather than dissipated into the air. As a result, the body must increasingly rely on sweat evaporation to encourage heat loss; this process is hindered in very humid climates. Wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) is a measure of heat stress that accounts for temperature, humidity, wind speed, and cloud cover. WBGT should be utilized to determine the relative risk of EHI based on local environmental conditions, as there is a direct correlation between elevated WBGT and risk of EHI.11,14 The greatest risk for EHS is performing high-intensity exercise (>75% VO2max) when WBGT >28°C (82°F).7 A study of hyperthermia-related deaths in football found that a majority of fatalities occurred on days classified as high risk (23°C-28°C) or extreme risk (>28°C) by WBGT.14 Consensus guidelines recommend that activities be modified based on WBGT (Table 2).7,12 The impact of WBGT does not end solely on the day of practice. Athletes who exercise in elevated WBGT environments on 2 consecutive days are at increased risk of EHI due to cumulative effects of exercise in heat.11Clothing. In football, required protective equipment may cover up to 60% of body surfaces. Studies have shown that wearing full uniform with pads increases internal body temperature and decreases time to exhaustion when compared to light clothing.5,15 In addition, athletic equipment traps heat close to the body and inhibits evaporation of sweat into the environment, thereby inhibiting radiant and evaporative heat dissipation.5,11 Likewise, wearing dark clothing encourages radiant absorption of heat, further contributing to potential thermal dysregulation.5 Use of a helmet is a specific risk factor for EHI, as significant heat dissipation occurs through the head.11 To mitigate these risk factors, the introduction of padded equipment should occur incrementally over the heat acclimatization period (see below). In addition, athletes should be encouraged to remove their helmets during rest periods to promote added heat dissipation and recovery.Heat Acclimatization. The risk of EHI escalates significantly when athletes are subjected to multiple stressors during periods of heat exposure, such as sudden increases in intensity or duration of exercise; prolonged new exposures to heat; dehydration; and sleep loss.5 When football season begins in late summer, athletes are least conditioned as temperatures reach their seasonal peak, causing increased risk of EHI.15 Planning for heat acclimatization is vital for all athletes who exercise in hot environments. Acclimatization procedures place progressively mounting physiologic strains on the body to improve athletes’ ability to dissipate heat, diminishing thermoregulatory and cardiovascular exertion.4,5 Acclimatization begins with expansion of plasma volume on days 3 to 6, causing improvements in cardiac efficiency and resulting in an overall decrease in basal internal body temperature.4,5,15 This process results in improvements in heat tolerance and exercise performance, evolving over 10 to 14 days of gradual escalation of exercise intensity and duration.5,10,11,16 However, poor fitness levels and extreme temperatures can prolong this period, requiring up to 2 to 3 months to fully take effect.5,7

The National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) have released consensus guidelines regarding heat acclimatization protocols for football athletes at the high school and college levels (Tables 3 and 4). Each of these guidelines involves an initial period without use of protective equipment, followed by a gradual addition of further equipment.11,16

Secondary Prevention

Despite physicians’ best efforts to prevent all cases of EHI, athletes will still experience the effects of exercise-induced hyperthermia. The goal of secondary prevention is to slow the progression of this hyperthermia so that it does not progress to more dangerous EHI.