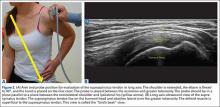

Some have recommended using the modified Crass or Middleton position to evaluate the supraspinatus, where the hand is in the “back pocket”.19 However, many patients with shoulder pain have trouble with this position. By resting the ipsilateral hand on the ipsilateral hip and then dropping the elbow, the supraspinatus insertion can still be brought out from under the acromion. This does bring the insertion anterior out of the scapular plane, so an adjustment is required in probe positioning to properly see the supraspinatus short and long axis. To find the long axis, the probe is placed parallel to a plane that spans the contralateral shoulder and ipsilateral hip (Figure 2A). The fibers of the supraspinatus should be inserting directly lateral to the humeral head without any intervening space (Figure 2B). If any space exists, a partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion (PASTA) lesion is present, and its thickness can be directly measured. Moving more posterior will show the flattening of the tuberosity and the fibers of the infraspinatus moving away from the humeral head—the bare spot. The MRI equivalent is the coronal view.

To view the supraspinatus tendon in short axis, maintain the arm in the same position, keeping the tendon in the center of the screen/probe. The probe is then rotated 90° on its center axis, keeping the tendon centered on the probe. The probe should now be in a parallel plane between the ipsilateral shoulder and the contralateral hip. The biceps tendon in cross-section will be found anteriorly, and the articular cartilage will appear as a black layer over the bone. Dynamic testing includes placing the probe in a coronal plane between the acromion and greater tuberosity. When the patient abducts the arm while in internal rotation, the supraspinatus tendon will slide underneath the coracoacromial arch showing potential external impingement.15 The MRI equivalent is the sagittal plane.

The glenohumeral joint is best viewed posteriorly, limiting how much of the intra-articular portion of the joint can be imaged. The arm remains in a neutral position; palpate for the posterior acromion and place the probe just inferior to it, wedging up against it (Figure 3A). The glenohumeral joint will be seen by keeping the probe parallel to the ground (Figure 3B). The MRI equivalent is the axial plane. If a joint effusion exists, it can be seen in the posterior recess.15 A hyperechoic triangular region in between the humeral head and the glenoid will represent the glenoid labrum (Figure 3B). By internally and externally rotating the arm, the joint and labrum complex can be dynamically examined. From the labrum, scanning superior and medial can sometimes show the spinoglenoid notch where a paralabral cyst might be seen.15

Using the glenohumeral joint as a reference, the infraspinatus muscle is easily visualized. Maintaining the arm in neutral position with the probe over the glenohumeral joint, the infraspinatus will become apparent as it lays in long axis view superficially between the posterior deltoid and glenohumeral joint (Figure 3B).16-20 The teres minor lies just inferiorly. The MRI equivalent is the axial plane. To view the infraspinatus and teres minor in short axis, the probe is then rotated 90° on its center axis. The infraspinatus (superiorly) and teres minor (inferiorly) muscles will be visible in short axis within the infraspinatus fossa.15 The MRI equivalent is the sagittal view.

The acromioclavicular joint is superficial and easy to image. The arm remains in a neutral position, and we can palpate the joint for easy localization. The probe is placed anteriorly in a coronal plane over the acromion and clavicle. By scanning anteriorly and posteriorly, a joint effusion referred to as a Geyser sign might be seen. The MRI equivalent is the coronal view.

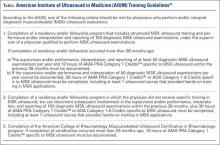

Available Certifications

The AIUM certification is a voluntary peer reviewed process that acknowledges that a practice is meeting national standards and aids in improving their respective MSK ultrasound protocols. They also provide guidelines on demonstrating training and competence on performing and/or interpreting diagnostic MSK examinations (Table).10 The ARDMS certification provides an actual individual certification referred to as “Registered” in MSK ultrasound.11 The physician must perform 150 diagnostic MSK ultrasound evaluations within 36 months of applying and pass a 200-question examination that is offered twice per year.11 None of these certifications are mandated by the American Medical Association (AMA) or American Osteopathic Association (AOA).

Maintenance and Continuing Medical Education (CME)

The AIUM recommends that a minimum of 50 diagnostic MSK ultrasound evaluations be performed per year for skill maintenance.10 Furthermore, 10 hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ or American Osteopathic Association Category 1-A Credits specific to MSK ultrasound must be completed by physicians performing and/or interpreting these examinations every 3 years.10 ARDMS recommends a minimum of 30 MSK ultrasound-specific CMEs in preparation for their “Registered” MSK evaluation.1