As total health care costs reach almost $3 trillion per year—capturing more than 17% of the total US gross domestic product—payers are searching for more effective ways to limit health care spending.1,2 One increasingly discussed plan is payment bundling.3 This one-lump-sum payment model arose as a result of rapid year-on-year increases in total reimbursements under the current, fee-for-service model. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hypothesized that a single all-inclusive payment for a procedure or set of services would incentivize improvements in patient-centered care and disincentivize cost-shifting behaviors.4 Bundled reimbursement is becoming increasingly common in orthopedic practice. With the recent introduction of the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Initiative, several orthopedic practices around the United States are already actively engaged in creating models for bundled payment for common elective procedures and for associated services provided up to 90 days after surgery.3,5

Bundled payment increases the burden on the provider to understand the cost of care provided during a care cycle. However, not only has the current system blinded physicians to the cost of care, but current antitrust legislation has made discussions of pricing with colleagues (so-called price collusion) illegal and subject to fines of up to $1 million per person and $100 million per organization,6 therefore limiting orthopedic physician involvement.

Given these legal constraints, instead of measuring direct costs of goods, we developed a “grocery list” approach in which direct comparisons are made of resources (goods and services) used and delivered during the entire 90-day cycle of care for patients who undergo anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). We used one surgeon’s practice experience as a model for measuring other orthopedic surgeons’ resource utilization, based on their electronic medical records (EMR) system data. By capturing the costs of the components of resource utilization rather than just the final cost of care, we can assess, compare, understand, endorse, and address these driving factors.

1. The significance of resource utilization

To maximize the efficiency of their practices, high-volume shoulder surgeons have introduced standardization to health care delivery.7 Identifying specific efficiencies makes uniform acceptance of beneficial practice patterns possible.

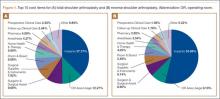

To facilitate comparison of goods and services used during an episode of surgical care, Virani and colleagues8,9 studied the costs of TSA and RSA and calculated the top 10 driving cost factors for these procedures (Figure 1). Their systematic analysis provided a framework for a common method of communication, allowing an orthopedic surgeon to gain a more complete understanding of the resources used during a particular operative procedure in his or her practice, and allowing several physicians to compare and contrast the resources collectively used for a single procedure, facilitating an understanding of different practice patterns within a local community. At a societal level, these data can be collected to help guide overall recommendations.

2. How we defined utilization

To define the resources used, we had to decide which procedure components cost the most. Virani and colleagues8,9 found that the top 10 cost drivers accounted for 93.11% and 94.77% of the total cost of the TSA and RSA care cycles, respectively (Figure 1). For each cost driver, information on resources used (goods, services, overhead) was collected on 2 forms, the Hospital Utilization Form (7 hospital-based items) and the Clinical Utilization Form (3 non-hospital-based items). To make hospital data easy to compile, we piloted use of a “smart form” in the EpicCare EMR system to isolate and auto-populate specific data fields.

3. EMR data collection

With EMR becoming mandatory for all public and private health care providers starting in 2014, utilization data are now included in a single unified system. Working with our in-house information technology department, we developed an algorithm to populate this information in a separate, easy-to-follow hospital utilization form. This form can be adopted by other institutions. Although EpicCare EMR is used by 52% of hospitals and at our institution, the data points required to make the same measurements are generalizable and exist in other EMRs.

Smartlinks, a tool in this EMR, allows utilization data to be quickly retrieved from different locations in a medical record and allows a form to be electronically completed in seconds. Data can be retrieved for any patient in the EMR system, regardless of when that patient’s hospital stay occurred. We populated data from surgeries performed 2 years before the start of this project.