Discussion

Von Rokitansky first described SMAS in the mid-1800s.1 The exact pathology was further defined 60 years later when vascular involvement was determined to be the definitive mechanism of obstruction.2-4 Superior mesenteric artery syndrome is caused by the superior mesenteric vessels compressing the third portion of the duodenum, resulting in an extrinsic obstruction. This syndrome is also commonly called Wilkie disease, after Dr. David Wilkie, who first published in 1927 results of a comprehensive series of 75 patients.1 The syndrome is also known as arteriomesenteric duodenal compression, aortomesenteric syndrome, chronic duodenal ileus, megaduodenum, and cast syndrome.1,4,5 The term cast syndrome was derived from events in 1878, when Willet applied a body cast to a scoliosis patient who died after what was termed “fatal vomiting.”3

Epidemiology, Incidence, and Prevalence

While not unheard of, SMAS is an uncommon disorder. There have been only 400 documented reports in the English-language literature since 1980.5-8 Studies have stated that the incidence of the affected population is less than 0.4%.5,7,9,10 However, SMAS has been reported to have a mortality rate as high as 33% because of the uncommon nature of the disease and prolonged duration between onset of symptoms and diagnosis.7,9,11,12 The incidence of SMAS is higher after surgical procedures to correct spinal deformities, with rates between 0.5% and 4.7%.10,12,13 Females are affected more frequently than males (3:2 ratio).1,9,14 One large study with 80 patients that spanned 10 years reported that female incidence was 66%, and another study with 75 patients also observed that two-thirds of the patients were women.1,7 This syndrome commonly affects patients who are tall and thin with an asthenic body habitus.1,6,11,12 Superior mesenteric artery syndrome develops more commonly in younger patients. Previous studies noted that two-thirds of patients were between ages 10 and 39 years.1,8 However, given the right set of medical conditions, it can occur in patients of any age.2,9,15,16 In young, thin patients with scoliosis, the risk of developing SMAS after spinal fusion with instrumentation increases, given their already low weight coupled with the surgical intervention at the height of their longitudinal growth spurt.1,11,12

Other patients also at increased risk for developing SMAS include those with anorexia nervosa, psychiatric/emotional disorders, or drug addiction. It can also be found in persons on prolonged bedrest, those who have increased their activity and lost weight volitionally, or patients with illness or injuries, such as burns, trauma, or significant postoperative complications that decrease caloric intake and keep them in a supine position.2,6,17 The syndrome can be acute or chronic in its presentation.

Anatomy and Physiology

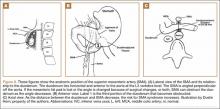

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) comes off the right anterolateral portion of the abdominal aorta, which is just anterior to the L1 vertebra. It passes over the third part of the duodenum, generally at the L2 level (Figure 8A). The duodenum passes across the aorta at the level of the L3 vertebral body and is suspended between the aorta and the SMA by the ligament of Treitz (Figure 8B).3 The angle between the aorta and SMA (aortomesenteric angle) typically ranges from 25º to 60º with an average of 45º (Figure 8A). The distance between the aorta and SMA at the level of the duodenum is called the aortomesenteric distance, and it normally measures from 10 mm to 28 mm. Obstruction is usually observed at 2 mm to 8 mm (Figure 8C).1,3

Compression and outlet obstruction from narrowing of the SMA aortomesenteric angle can be caused by a multitude of problems.3,5,9,17 In chronic conditions, narrowing of the aorto-mesenteric angle could be the result of a shortened ligament, or a low origin of the SMA on the aorta, or a high insertion of the duodenum at the ligament of Treitz. Postoperatively, any change in anatomy caused by adhesions could result in compression as well. Most commonly, however, in those with significant weight loss, such as postoperative spinal fusion patients, there is loss of retroperitoneal fat, which normally acts as a cushion around the duodenum. This allows the SMA to move posteriorly obstructing the duodenum. Lying in a recumbent position along with weight loss also puts patients at risk after surgery.3,5,9,17 SMAS should be distinguished from other conditions that can cause duodenal obstruction, such as duodenal hematomas and congenital webs.

Symptoms and Patient Presentation

Whether SMAS is acute or chronic, most patients with SMAS present in a similar fashion. Almost all patients with acute SMAS complain of abdominal pain, nausea, and emesis (usually bilious) that usually occur after eating. Early satiety is commonly observed, resulting from delayed gastric emptying. Abdominal pain may improve when patients lie prone and are in the knee-chest, or lateral decubitus, position. These patients frequently have upper abdominal distention because of massive retention of gastric contents.4,6,16,18,19 Most spinal fusion patients present with these symptoms 7 to 10 days after surgery.11-13