The relationship and collaboration between orthopedic surgeons and the orthopedic industry are considerable. Orthopedic surgeons can provide companies with important clinical input into the design of implants, facilitate commercialization of innovations developed by clinician entrepreneurs, and help provide rapid dissemination of new technologies.1,2 However, these relationships can result in conflicts of interest, thereby influencing the physicians’ judgment and choices and ultimately patient care.3,4 Making these potential conflicts transparent through physician disclosures is an accepted way to limit the negative effects of these relationships.5 The relationship between orthopedic surgeons and industry was brought to the forefront in 2007 with a settlement between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the 5 largest orthopedic implant makers.6 Among other things, this settlement required that each company publicly disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of all surgeons and organizations it paid, and how much. The DOJ settlement was one of the impetuses that led many orthopedic societies to adopt either voluntary or mandatory disclosure policies for their members.

In 2007, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an orthopedic disclosure program to promote transparency and confidence in its educational programs and decisions.7 One of the 2 main purposes of the disclosure program is “streamlining the disclosure process for orthopedic surgeons and others involved in organizational governance, all formats of continuing medical education [CME] and authors of enduring materials, clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and appropriate use criteria (AUC) development and editors-in-chief and editorial boards, from whom disclosure is required.”8 Disclosure is mandatory only for participants in the AAOS CME programs (including any podium or poster presentation) or authors of enduring materials; members of the AAOS Board of Directors, Board of Councilors, Board of Specialty Societies, councils, cabinets, committees, project teams, or other AAOS governance groups; editors-in-chief and editorial boards; and AAOS guideline development workgroups. Members who fail to disclose are informed they cannot participate in AAOS activities. All other members of the organization are not required to disclose any industry-related relationships, and any disclosure is completely voluntary.7 This seems contrary to the second main goal of the disclosure policy: “increase transparency throughout AAOS by making this disclosure program available to the public and to AAOS members.”8

We conducted a study to compare the disclosures posted by the top orthopedic companies with the disclosures made by their surgeon-consultants and to determine how many of these surgeons have disclosed this information on the AAOS website.

Materials and Methods

On November 26, 2012, we reviewed the websites of the top 13 orthopedic device companies by revenue (Stryker, DePuy Orthopaedics, Zimmer Holdings, Smith & Nephew, Synthes, Medtronic Spine, Biomet, DJO Global, Orthofix, NuVasive, Wright Medical Group, ArthroCare, Exactech)9 to identify their surgeon-consultants for 2011. We excluded non-US surgeons (DOJ disclosure not required), revenues under $1000, and reimbursement for meals and travel. Although the DOJ settlement required that each company disclose on its website, beginning in 2008, the names and locations of its paid consultants and the amounts paid, the settlement did not stipulate how long this must be continued. Of the 13 companies, only 6 (Stryker, DePuy, Smith & Nephew, Medtronic, Wright, Exactech) continued listing and updating surgeon disclosure information.

As the companies differed in how they defined surgeon consulting services, we defined surgeon-consultant payments as the sum of consulting payments, royalty payments, and research support. We searched for each surgeon-consultant’s name in the AAOS orthopedic disclosure program database.7 From the database, we determined whether the surgeon was a member of AAOS. All members were then categorized into those who disclosed all their payments, those who incompletely disclosed their payments, those who did not disclose any payments, and those who did not provide any information. They were then subdivided into those who had and had not participated in CME activities at the AAOS annual meeting in 2011 (participants were listed in the meeting proceedings). This does not take into account AAOS members who presented at other AAOS-sponsored CME courses during 2011 and who therefore were required to disclose. The information was categorized by company, payment amount, and overall. To simplify matters and deal with varying corporate categories, we divided payments into 4 amount groups: less than $10,000, $10,000 to $100,000, $100,001 to $1 million, and more than $1 million. Some orthopedic companies reported surgeon payments as categorical rather than exact amounts. In these cases, we coded the payment as the midpoint of the range.

Results

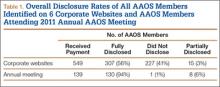

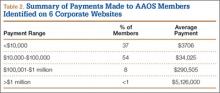

Overall, 549 AAOS members received payments of more than $1000 from at least 1 of the 6 companies. Of these surgeons, 307 (56%) fully disclosed their payments, and 242 (44%) did not (Table 1). Of the 32 surgeons who were on 2 corporate payment lists, 24 disclosed both companies, 6 disclosed only 1 company, and 2 failed to disclose either company. AAOS members who did not disclose payments received less than $10,000 (average, $3706) in 37% of cases (Table 2), between $10,000 and $100,000 (average, $34,025) in 54% of cases, between $100,001 and $1 million (average, $290,505) in 8% of cases, and more than $1 million (average, $5,126,000) in less than 1% of cases.