Iliosacral (SI) screws remain the standard of care for the vast majority of posterior pelvic ring disruptions.1,2 However, despite their routine use, the procedure remains technically demanding with repeated cases of aberrant screw placement and complications.3,4 Sacral morphology is extremely variable within a patient population and affects accurate placement and trajectory of percutaneous screws.5 Classically, it is taught that the external starting position/landmark is at an intersection point of the greater trochanter and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). While this “one size fits all” approach will certainly help to coordinate a start position, it is our experience that multiple stab incisions are necessary to find the optimal start site. To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side, guided by the lateral image.5 This article provides a novel image-based technique to be used with, or as a replacement for, the traditional technique.

Techniques

The patient is brought to the operating room and placed supine on a radiolucent operating table. If the closed reduction of the pelvic ring is successful or can be achieved via anterior manipulation/traction, posterior percutaneous pinning is planned. Either a rolled towel or a bag of saline is used as a bolster and placed midline underneath the sacrum and lumbar spine to help “bump” the pelvis and improve the range of motion for the surgeon’s drill. The patient is brought to the edge of the table when possible (ie, a posterior ring injury requiring fixation from only 1 side) to further enhance drill motion. If bilateral screws are planned, surgeons must be careful not to position 1 side at the expense of screw placement on the contralateral side. Nitrous-based anesthetic agents are avoided, because they may collect in the bowel and obscure good radiographic visualization. Arms are placed perpendicular to the body to facilitate the inlet view. Pre-preparation anteroposterior pelvis, inlet, and outlet views are obtained to assure ability to accurately and safely assess landmarks on all projections, and to mark the C-arm position and angles. This process helps decrease “useless” radiographs obtained during the procedure. Acceptable inlet radiographs show the anterior cortex of the S1 body superimposed on the S2 body. Acceptable outlet radiographs show the superior pubic symphysis at the level of the S2 foramen and visualization of the S1/S2 sacral foramen.6 The patient is then prepared in the standard fashion. Reduction maneuvers are performed and, if acceptable alignment is achieved, posterior percutaneous screw placement begins.

Technique 1

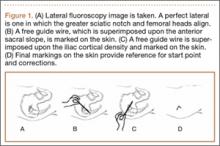

To our knowledge, the most common image-based technique used to guide start-point localization and placement of SI screws begins with drawing a virtual sacrum on the patient’s side using the lateral image. The fluoroscopic machine is set up in a lateral position.5 A free guide wire is superimposed upon the iliac cortical density and anterior sacral slope, which is marked on the skin (Figure 1). The superior portion of S1, as well as the posterior sacral slope, can be marked as well. This process has outlined the sacrum and provides an external landmark for the “safe zone” for screw placement. The operation proceeds in the standard fashion using inlet, outlet, and lateral radiographs. However, the externally drawn sacrum can aid as a reference during guide-pin placement.

Technique 2

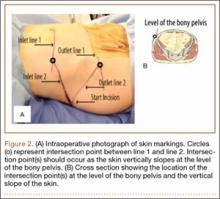

This technique takes into account bone anatomy and soft-tissue coverage. It is helpful to think of the abdomen/pelvis as a box. The anterior abdomen represents the top of the box and the lateral buttock represents the side of the box. The corner of the imaginary box is where the abdomen begins to slope down and transitions laterally to become the buttock. This will be referenced as the “down-sloping point” and typically corresponds to the level of the iliac crest (Figure 2).

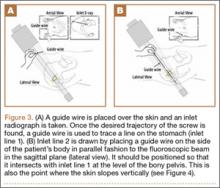

To begin, a standard cannulated screw guide wire is placed flush on the skin of the abdomen. An inlet fluoroscopy image is taken with the guide pin on the abdomen. Imagine that the resulting image represents the planned screw trajectory (Figure 3A). When the position of the guide wire is deemed adequate, a line is marked on the abdomen, using a pen, directly adjacent to the guide wire. This line represents inlet line 1 (Figure 2). The line must continue laterally until the down-sloping point. The sagittal angle of the imaginary inlet fluoroscopic beam is noted, and a guide wire is placed in the same sagittal orientation flush with the skin on the lateral buttock (Figure 3B). The guide wire must be placed so that it intersects with the first line at the down-sloping point. The skin on the lateral aspect of buttock is marked with a second line, which represents inlet line 2 (Figure 2).