Dear Dr. Mossman,

Some of my patients e-mail me questions about their prescriptions, test results, treatment, appointments, etc. I’m often unsure about the best way to respond. If I use e-mail to communicate with patients, what step(s) should I take to minimize medicolegal risks?

Submitted by “Dr. V”

Medicine adopts new communication technologies cautiously. Calling patients seems unremarkable to us now, but it took decades after the invention of the telephone for doctors to feel comfortable talking to patients other than in face-to-face meetings.1,2

Patients want to communicate with their physicians via electronic mail,3 but concerns about security, confidentiality, and liability stop many physicians from using e-mail in their practice. Yet many medical organizations, including the Institute of Medicine,4 the American Medical Association,5 and the American Psychiatric Association,6 recognize that e-mail can facilitate care, if used properly.

Although e-mailing patients may feel awkward, a growing minority of clinicians regularly use e-mail for patient communication.2,7 In this article, we discuss ways to help safeguard your patients and their communications and to protect yourself from legal headaches.8

As you’re reading, please remember that we’re discussing communications to patients through standard e-mail, not secure portals (such as MyChart) that allow patients to contact physicians confidentially through their electronic medical records.

Privacy and security

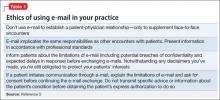

Doctor-patient e-mails implicate the same professional, ethical, and legal responsibilities that govern any communication with patients.2,9,10 If handled improperly, outside-the-office doctor-patient communication can breach traditional duties to protect confidentiality, or they can violate provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).11 Confidentiality breaches can lead to malpractice litigation, and HIPAA infractions can result in civil and criminal penalties levied by federal agencies.12 Further, e-mails that breach ethical standards (Table 15) can generate complaints to your state’s medical licensure board.

E-mail appeals to many patients, if for no other reason than to save time or avoid the inconvenience of playing “phone tag” with the doctor’s office. But e-mail has drawbacks. Patients may think or behave as though online communications are intimate and confidential, but they usually aren’t. If e-mail programs are left open or aren’t password protected, friends and family members might look at messages and even act upon them. For this reason, doctors often cannot be sure whether they are communicating with the patient or with someone else who has gained access to the patient’s e-mail account.

Parties outside the treatment relationship could have access to e-mail data stored on servers.6 Also, it’s easy to misread or mistype an e-mail address and send confidential information to the wrong person. A truly “secure” e-mail exchange uses encryption software that protects messages during transmission and storage and requires users to authenticate who they are through actions that link their identity to the e-mail address.13 But some patients and physicians do not know about the availability of such security measures, and implementing them can feel cumbersome to those who are not computer savvy. Not surprisingly, then, recent studies have shown that such measures are used infrequently by physicians and patients.14

Topics for e-mail communication

One way to minimize potential privacy problems is to limit the topics and types of communication dealt with by e-mail. Several experts and organizations have published suggestions, recommendations, and resources for doing this with common practices (Table 2).6,7,15

Receiving e-mail permission

Many patients e-mail their physicians without the physicians’ prior agreement. But physicians who plan to use e-mail in their practice should get patients’ explicit consent. This can be done verbally, with the content of the discussion documented in the medical record. But it’s better to have patients authorize e-mail communications in writing by means of a permission form that also sets out your office’s e-mail policies, expected response times, and privacy limitations.

Commonly recommended contents of such forms5-7,9,15,16 include:

• discussing security mechanisms and limits of security

• e-mail encryption requirements (or waiving them, if the patient prefers)

• providing an expected response time

• indemnifying you or your institution for information loss caused by technical failure

• identifying who reads e-mails (eg, office staff members, a nurse, physician [only])

• asking patients to put their name and other identifying information in the body of the message, not the subject line

• asking patients to put the type of question in the subject line (eg, “prescription,” “appointment,” “billing”)

• asking patients to use the “auto reply” feature to acknowledge receipt of your messages.

In addition to using patient consent forms, other suggestions and recommendations for physicians include:

• Do not use e-mail to establish patient-physician relationships, only to supplement personal encounters.

• If you work for an agency or institution, know and follow its guidelines and policies.

• If a rule or “boundary” is breached (eg, a patient sends you a detailed e-mail on a topic beyond the scope of your previous agreement), address this directly in a treatment session.

• File e-mail correspondence, including your reply, in the patient’s medical record.

• Use encryption technology if it is available, practical, and user-friendly.

• Use a practice-dedicated e-mail address with an automatic response that explains when e-mail will be answered and reminds patients to seek immediate help for urgent matters.