• obesity (adults and children)

• diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance

• cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

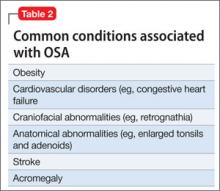

Obesity is one of the primary and more modifiable risk factors for OSA (Box). Studies suggest that reducing the severity of obesity would likely benefit people with a sleep disorder, and that treating sleep deprivation and sleep disorders might benefit persons with obesity.12 Chronic sleep loss can have a deleterious influence on appetite regulation through effects on 2 hormones, leptin and ghrelin, that play a major role in appetite regulation. Chronic sleep loss causes and perpetuates obesity through its interplay with these, and other, hormones.12

Diabetes. The link between obesity and diabetes is well-established, as is the long-term morbidity and mortality of these 2 diseases.13 Evidence shows that OSA is associated with impaired glucose tolerance and an increased risk of diabetes.14

Cardiovascular disease. OSA has a strong association with cardiovascular disease, including systemic hypertension, possibly myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke.15 Institution of appropriate treatment for OSA including CPAP can minimize or reverse many of these effects.16

Making an OSA diagnosis

A diagnostic polysomnogram (PSG), or sleep study, is the standard test when OSA is suspected. It is performed most often at an attended sleep laboratory. Typically, a PSG measures several physiologic measures, including, but not limited to:

• airflow through mouth and nose

• stages of sleep (by means of electroencephalography channels)

• thoracic and abdominal movements (to assess effort of breathing)

• muscle activity of the chin

• oxyhemoglobin saturation (to monitor variability in oxygen saturation [SaO2] during OSA events).

Portable diagnostic instruments can provide reliable information when a patient cannot be studied in a laboratory. Assessments available on portable instruments include cardiopulmonary monitoring of respiration only; PSG; and peripheral arterial tonometry, which measures autonomic manifestations of respiratory obstructive events.17,18

The severity of OSA is established by the apnea/hypopnea index, which measures the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep.

How is OSA treated?

CPAP is still the gold standard for treating OSA. CPAP provides a pneumatic splint for the upper airway by administering positive pressure through a nasal or oronasal mask. CPAP distinctly improves daytime sleepiness.19,20

Pressure is determined initially by titration during PSG, although a number of automated CPAP machines are available in which pressure is adjusted based on the machine’s response to airflow obstruction. Advantages of using PSG to titrate CPAP are direct observation to control mask leak and the ability to observe the effects of body position and sleep stage and clearly distinguish periods of sleep from wakefulness.

Regrettably, adherence to a nightly regimen of CPAP is less than ideal for several reasons, including claustrophobia, interface failure, and other motivational variables. Some patients who experience claustrophobia can use desensitization techniques; others are, ultimately, unable to use the mask.

Oral appliances. A patient who has mild or moderate OSA but who cannot use the CPAP mask might be a good candidate for an oral appliance. These appliances, which hold the mandible in an advanced position during the night, can be effective in such cases.

CPAP autotitration changes the treatment pressure based on feedback from such patient measures as airflow and airway resistance. Autotitrating devices might have a role in beginning treatment in patients with OSA by means of a portable sleep study, in which CPAP titration is not performed. In addition, autotitrating offers the possibility of changing pressure over time—such as with changes in position during the night or over the longer term in response to weight loss or gain.

Surgery. In patients who are unable to use CPAP, surgery might be indicated to relieve an anatomical obstruction, such as adenotonsillar hypertrophy or other type of mass lesion.

Sleep positioning. A patient who demonstrates OSA exclusively while sleeping supine might benefit from being trained to sleep on either side only or arranging pillows so that he can only sleep on his side.

In conclusion

OSA is common and easily treatable. It coexists with, and exacerbates, medical and psychiatric illness. Treating OSA concomitantly with comorbid medical and psychiatric illness is essential to achieve full symptom remission and prevent associated long-term consequences of both medical and psychiatric illness.

BOTTOM LINE

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and psychiatric illness, especially depression, often co-exist. Screen depressed patients—especially those with risk factors for OSA, such as obesity, smoking, and an upper-airway abnormality—for a sleep disorder. This is especially important if a patient complains of daytime somnolence, fatigue, cognitive problems, poor concentration, or weight gain. For optimal results, treat comorbid psychiatric illness and OSA concurrently; the same is true for other sleep disorders.