The authors’ observations

In Mr. M’s case, Facebook served as a vehicle through which he could pursue a non-bizarre delusion. Mr. M openly admitted to viewing his twin brother as a rival; it is not surprising, therefore, that his delusions targeted his brother and ex-girlfriend.

Before social networks, the perseveration of this delusion might have been limited to internal thinking, or gathering corroborative information by means of stalking. Social media outlets have provided a means to perseverate and implicate others remotely, however, and Mr. M soon expanded his delusions to include more peers.

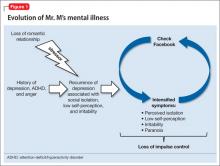

After beginning to suspect that friends and family are commenting on or criticizing him through Facebook, Mr. M experienced an irresistible impulse to repeatedly check the social network, which may have provided short-term relief of anticipatory anxiety, but that perpetuated the cycle. Constant access to the internet facilitated and intensified Mr. M’s cycle of paranoia, anxiety, and dysphoria. He called this process an “addiction.” A conceptual framework of the development of Mr. M’s maladaptive use of Facebook is illustrated in Figure 1.

Risk factors

Insecurity with one’s self-worth also may be a warning sign. Online social networking circumvents the need for physical interaction. A Facebook profile allows a person to selectively portray himself (herself) to the world, which may not be congruous with how his peers see him in everyday life. Patients who fear criticism or judgment may be more prone to maladaptive Facebook use, because they might feel empowered by the control they have over how others see them—online, at least.

Limited or, in Mr. M’s case, singular romantic experience may have influenced the course of his illness. Mr. M described his romantic involvement as a single, tumultuous relationship that lasted several years. Young patients with limited romantic experience may struggle to develop healthy protective mechanisms and may become preoccupied with the details of the situation, such that it interferes with functioning.

Mr. M’s history of ADHD might be a risk factor for abnormal patterns of internet use. Patients with ADHD have increased attentiveness with visually stimulating tasks—specifically, computers and video games.12

Last, it is unclear how, or if, Mr. M’s history of head injury contributed to his symptoms. There were no clear, temporal changes in cognition or emotion associated with the head injury, and he did not receive regular follow-up. Significant cognitive impairment does not appear to be a factor.

a) restart fluoxetine

b) begin an atypical antipsychotic

c) begin a mood stabilizer and atypical antipsychotic

d) encourage Mr. M to deactivate his Facebook account

TREATMENT: Observed use

Quetiapine is selected to target psychosis, agitation, and insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep initiation. Risperidone is added as a short-term agent to boost antipsychotic effect during the day when Mr. M is not fully responsive to quetiapine alone. Valproic acid is added on admission as a mood stabilizer to target emotional lability, impulsiveness, and possible mania.

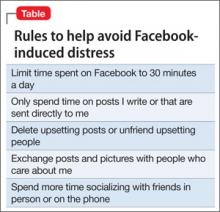

After several days of treatment, and without access to a computer, Mr. M is calmer. We begin to assess the challenges of self-limiting time spent on Facebook; Mr. M explains that, before hospitalization, he had deactivated his Facebook account several times to try to rid himself of what he describes as an “addiction to social media”; soon afterward, however, he experienced overwhelming anxiety that led him to reactivate his account.

We sit with Mr. M as he logs in to Facebook and discuss the range of alternative explanations that specific public messages on his news feed could have. Explicitly listing alternative explanations is a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Mr. M begins to demonstrate increased insight regarding his paranoia and possible misinterpretation of information gleaned via Facebook; however, he still believes that masked references to him had existed. During his hospital stay he begins to acknowledge the problems that online interactions pose compared with face-to-face interactions, stating that, “There’s no emotion in [Facebook], so you can easily misinterpret what someone says.”