Patients with post-stroke depression (PSD) pose many clinical dilemmas: Is their depression a psychological reaction or a biological event? Are antidepressants effective for either type? Should antidepressants be given prophylactically after a stroke, even if the patient is not depressed?

Although the answers are not clear, this article describes a practical approach to stroke patients referred for psychiatric evaluation, including:

- strategies to distinguish reactive from endogenous depression

- issues that guide antidepressant selection

- benefits and risks of using medication to prevent depression after an acute stroke.

Reactive or endogenous depression?

Each year 500,000 to 600,000 Americans suffer strokes.1 Depression is the most common emotional sequela, reported in up to 40% of survivors within several months of an acute stroke.

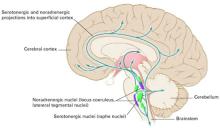

Figure Possible mechanism for endogenous post-stroke depression

Anterior cerebrovascular lesions may block serotonergic and noradrenergic projections into the superficial cortex. The closer the lesion to the nuceli, the greater the pathway interruption, and the more severe the depression may be. Drawing represents nuclei in the brainstem, slightly enlarged, with their projections greatly simplified.

Source: Reference 8

Illustration for Current Psychiatry by Marcia Hartsock, CMIPSD is characterized as reactive (related to physical and psychosocial losses of stroke) or endogenous (a biologic consequence of stroke).

Reactive depression. Patients exhibit a constellation of emotional symptoms while attempting to cope with a new physical or cognitive deficit. This “catastrophic reaction”2 includes anxiety, crying, aggressive behavior, cursing, refusal, displacement, renouncement, and sometimes compensatory boasting.

In 62 stroke patients evaluated with the Catastrophic Reaction Scale:

- approximately 20% had a catastrophic reaction

- the reaction was significantly associated with major depression.

Anterior subcortical damage may be the common mechanism underlying both catastrophic reaction and major depression in stroke patients.3

Post-stroke emotional lability resembles PSD. This “pathologic emotion” or “emotional incontinence” can manifest as sudden, frequent, easily-provoked episodes of crying that are generally mood-congruent. Affected patients may also respond to nonemotional events with outbursts of pathologic crying or laughing.

The pathogenesis of post-stroke emotional lability is unclear, although biogenic amines may play a role. In a 6-week, double-blind trial, 28 patients with post-stroke pathologic laughter and crying were treated with nortriptyline or placebo. Symptoms improved significantly more with nortriptyline in both depressed and nondepressed patients, indicating that the response was not related simply to improved depressive symptoms.4

Endogenous depression. Robinson et al5 propose a neuroanatomic PSD model. They contend that major—but not minor—PSD correlates with the stroke lesion’s proximity to the left anterior frontal pole or underlying basal ganglia. Other investigators, however, question this anatomic distinction between major and minor PSD.

For example, Gainotti et al6 used their own Post-Stroke Depression Rating Scale to compare stroke patients without depression, with minor depression, or with major depressive disorder (MDD) and a group of nonstroke patients with functional MDD. They found that:

- the phenomenology of patients with major PSD was more similar to that of patients with minor PSD than to that of patients with functional major depression

- major and minor PSD were much more likely to be associated with reactive depression than with the endogenous form.

Other researchers disputed the neuroanatomic model after failing to confirm a correlation between PSD and the location of lesions in the left hemisphere.7

Most recently, a meta-analysis by Narushima et al8 suggested a moderately strong correlation between depressive symptom severity and the distance between the anterior border of a left-hemispheric lesion and the frontal pole during the first 6 months following a stroke. This group hypothesizes that more-anterior lesions interrupt the brain’s serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways (Figure) at a site closer to their origin—before they branch posteriorly into the superficial cortex. This interruption presumably increases serotonin and noradrenergic depletion, which is manifest as depression.

A common denominator? Two other recent studies suggest that depression may be a significant independent risk factor for stroke:

- A prospective study has assessed stroke risk factors in 2,800 Australians since 1988. Depression has been a significant stroke risk factor in men and women ages 70 and older.9

- A population-based study showed that depression predicted stroke across all strata in a cohort of 6,000 men and women ages 25 to 74. Subjects were stroke-free at enrollment and followed for up to 22 years.10

Table 1

How to evaluate a patient for post-stroke depression (PSD)

|