Nasal continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP) should be started in an observed setting so that the clinician can determine the optimal amount of positive pressure needed to keep the upper airway patent.

For some patients, CPAP is started in the second half of a “split-night” sleep study after a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is made. Other patients return a second night for a nasal CPAP trial. Those with severe OSA might notice improved sleep quality and reduced EDS after only a few hours of CPAP use. Some wish to start CPAP treatment immediately.

Advances in masks and equipment have improved patient adherence to CPAP. Innovations include auto-titrating machines, in which the pressure level can be varied depending on sleep state or body position. Many machines include a data microchip that allows the clinician to determine duration of usage, then use that information to counsel the patient about adherence, if necessary.

Patient education also can promote CPAP adherence. When patients are first told they might need to sleep each night wearing a nasal mask, they often voice well-founded concerns about comfort, claustrophobia, or sexual activity.

Obtaining the support of the bed partner by welcoming her or him to all appointments, including educational activities, is optimal. The bed partner’s concerns about the patient’s excessive snoring or apneas probably were the impetus for the appointment in the first place.

Medication. Some patients benefit from 1 to 2 weeks of a sleeping medication such as zolpidem or trazodone while they acclimate to using nasal CPAP.

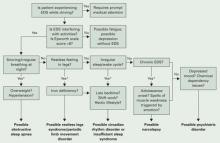

Figure The sleepy patient: Possible medical and psychiatric explanations

* Supportive factors: Persuasive if present, but if absent do not exclude possible conditions

Obstructive sleep apnea

Because OSA affects at least 4% of men and 2% of women,6 you are virtually assured of seeing undiagnosed patients. OSA is caused by repeated collapse of the soft tissues surrounding the upper airway, decreasing airflow that is restored when the patient briefly awakens. Patients develop EDS because sleep is fragmented by frequent arousals.

Obese patients, because of their body habitus, are at higher risk for OSA than patients at normal weight. Carefully screen patients for OSA if they develop weight problems while taking psychotropics, such as antipsychotics.

Alcohol or sedatives used at bedtime can aggravate OSA. These substances promote muscle relaxation and increase the arousal threshold so that patients do not awaken readily when apneas occur.

Long-term complications of untreated OSA include sleepiness leading to accidents, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and progressive obesity. Data also associate OSA with cardiovascular complications such as arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction.7

Physical examination focuses on detecting:

- nasal obstruction (have patient sniff separately through each nostril)

- large neck

- crowded oropharynx (low-hanging palate, reddened uvula, enlarged tonsils, large tongue relative to oropharynx diameter)

- jaw structure (particularly a small, retrognathic mandible).

Sleep studies. Referral for nocturnal polysomnography might be the next step. A comprehensive sleep study collects data about respiratory, cardiovascular, and muscle activity at night, as well as the sounds the patient makes—such as snoring or coughing—when asleep. EEG monitoring also is performed. OSA may be diagnosed if repeated episodes of reduced airflow and oxygen desaturation (arousals) are observed as brief shifts in EEG frequency.

Treatment. First-line interventions for the patient with OSA include:

- no alcohol 1 to 2 hours before bedtime

- sleeping on the side instead of the back

- weight loss (ideally with exercise)

- nasal sprays for allergies.

If first-line treatments are ineffective, nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) works well for most patients who adhere to the regimen.8 CPAP requires the patient to wear a nasal mask that delivers room air, splinting open the nasopharynx and upper airway (Box 2).

Surgical options. The most common surgeries for OSA are uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty. Others include tongue reduction and mandibular advancement.

The response rate to surgery averages 50%, depending on patient characteristics and procedure.9 Positive outcomes are most likely for thin patients with obvious upper airway obstruction, including deviated nasal septum, large tonsils, low-hanging palate, and large uvula. Postsurgical complications include nasal regurgitation, voice change, pain, bleeding, infection, tongue numbness, and snoring without apnea (silent apnea).

Oral appliances open the oropharynx by moving the mandible and tongue out of way. Patients with mild to moderate OSA accept these devices well. Evidence suggests that oral appliances improve sleep and reduce EDS more effectively than nasal CPAP and are preferred by patients.10

Oral devices have drawbacks, however. In most settings, their effectiveness cannot be observed during a “split-night” laboratory sleep study because the patient has not yet purchased the device. Also, multiple visits sometimes are required to custom-fit the appliance; this can pose a hardship for patients who live a distance from the provider.