Dr. A has been treating Ms. W, a graduate student, for depression. Ms. W made subtle comments expressing her interest in pursuing a romantic relationship with her psychiatrist. Dr. A gently redirected her, and she seemed to respond appropriately. However, over the past 2 weeks, Dr. A has seen Ms. W at a local park and at the grocery store. Today, Dr. A is startled to see Ms. W at her weekly yoga class. Dr. A plans to ask her supervisor for advice.

Dr. M is a child psychiatrist who spoke at his local school board meeting in support of masking requirements for students during COVID-19. During the discussion, Dr. M shared that, as a psychiatrist, he does not believe it is especially distressing for students to wear masks, and that doing so is a necessary public health measure. On leaving, other parents shouted, “We know who you are and where you live!” The next day, his integrated clinic started receiving threatening and harassing messages, including threats to kill him or his staff if they take part in vaccinating children against COVID-19.

Because of their work, mental health professionals—like other health care professionals—face an elevated risk of being harassed or stalked. Stalking often includes online harassment and may escalate to serious physical violence. Stalking is criminal behavior by a patient and should not be constructed as a “failure to manage transference.” This article explores basic strategies to reduce the risk of harassment and stalking, describes how to recognize early behaviors, and outlines basic steps health care professionals and their employers can take to respond to stalking and harassing behaviors.

Although this article is intended for psychiatrists, it is important to note that all health professionals have significant risk for experiencing stalking or harassment. This is due in part, but not exclusively, to our clinical work. Estimates of how many health professionals experience stalking vary substantially depending upon the study, and differences in methodologies limit easy comparison or extrapolation. More thorough reviews have reported ranges from 2% to 70% among physicians; psychiatrists and other mental health professionals appear to be at greater risk than those in other specialties and the general population.1-3 Physicians who are active on social media may also be at elevated risk.4 Unexpected communications from patients and their family members—especially those with threatening, harassing, or sexualized tones, or involving contact outside of a work setting—can be distressing. These behaviors represent potential harbingers of more dangerous behavior, including physical assault, sexual assault, or homicide. Despite their elevated risk, many psychiatrists are unaware of how to prevent or respond to stalking or harassment.

Recognizing harassment and stalking

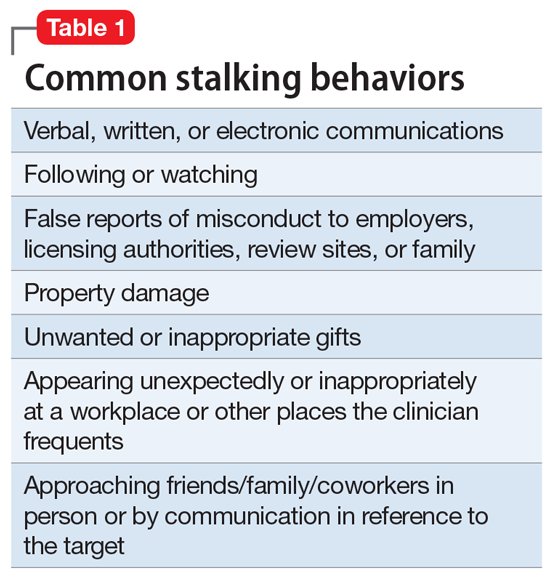

Repeated and unwanted contact or communication, regardless of intent, may constitute stalking. Legal definitions vary by jurisdiction and may not align with subjective experiences or understanding of what constitutes stalking.5 At its essence, stalking is repeated harassing behaviors likely to provoke fear in the targeted person. FOUR is a helpful mnemonic when conceptualizing the attributes of stalking: Fixated, Obsessive, Unwanted, and Repetitive.6Table 1 lists examples of common stalking behaviors. Stalking and harassing behavior may be from a known source (eg, a patient, coworker, or paramour), a masked source (ie, someone known to the target but who conceals or obscures their identity), or from otherwise unknown persons. Behaviors that persist after the person engaging in the behaviors has clearly been informed that they are unwanted or inappropriate are especially concerning. Stalking may escalate to include physical or sexual assault and, in some cases, homicide.

Stalking duration can vary substantially, as can the factors that lead to the cessation of the behavior. Indicators of increased risk for physical violence include unwanted physical presence/following of the target (“approach behaviors”), having a prior violent intimate relationship, property destruction, explicit threats, and having a prior intimate relationship with the target.7

Stalking contact or communication may be unwanted because of the content (eg, sexualized or threatening tone), location (eg, at a professional’s home), or means (eg, through social media). Stalking behaviors are not appropriate in any relationship, including a clinical relationship. They should not be treated as a “failure to manage transference” or in other victim-blaming ways.

There are multiple typologies for stalking behavior. Common motivations for stalking health professionals include resentment or grievance, misjudgment of social boundaries, and delusional fixation, including erotomania.8 Associated psychopathologies vary significantly and, while some may be more amenable to psychiatric treatment than others, psychiatrists should not feel compelled to treat patients who repeatedly violate boundaries, regardless of intent or comorbidity.

Patients are not the exclusive perpetrators of stalking; a recent study found that 4% of physicians surveyed reported current or recent stalking by a current or former intimate partner.9 When a person who is a victim of intimate partner violence is also stalked as part of the abuse, homicide risk increases.10 Workplace homicides of health care professionals are most likely to be committed by a current or former partner or other personal acquaintance, not by a patient.11 Workplace harassment and stalking of health care professionals is especially concerning because this behavior can escalate and endanger coworkers or clients.

Continue to: Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure...