Malphurs and Cohen5 (2002) reviewed American newspapers from 1997 through 1999 and identified 673 homicide-suicide events, of which 152 (27%) were committed by individuals age ≥55 years. The victims and perpetrators (95% of which were men) were intimate partners in three-quarters of cases. In nearly one-third of cases, caregiving was a contributing factor for the homicide-suicide. A history of or a pending divorce was reported in nearly 14% of cases. Substance use history was rarely recorded. Firearms were used in 88% of the homicide-suicide cases.5

Malphurs and Cohen17 (2005) reviewed coroner records between 1998 and 1999 in Florida and compared 20 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide involving perpetrators age ≥55 years with matched suicide decedents. They found that 60% of homicide-suicide perpetrators had documented health issues. The authors reported that a “recent change in health status” was more prevalent among perpetrators compared with decedents. Perpetrators were also more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. The authors found that 65% of perpetrators were reported to have a “depressed mood” and 15% of perpetrators had reportedly threatened suicide prior to the incident. However, none of the perpetrators tested positive for antidepressants as documented on post-mortem toxicology reports. Firearms were used in 100% of homicide-suicide cases.17

Salari3 (2007) reviewed multiple American media sources and published police reports between 1999 and 2005 to retrieve data about intimate partner homicide-suicide events in the United States. There were 225 events identified where the perpetrator and/or the victim were age ≥60 years. Ninety-six percent of the perpetrators were men and most homicide-suicide events were committed at the home. A history of domestic violence was reported in 14% of homicide-suicide cases. Thirteen percent of couples were separated or divorced. The perpetrator and/or victim had health issues in 124 (55%) events. Dementia was reported in 7.5% of cases, but overwhelmingly among the victims. Substance abuse was rarely mentioned as a contributing factor. In three-quarters of cases where a motive was described, the perpetrator was “suicidal”; however, a “suicide pact” was mentioned in only 4% of cases. Firearms were used in 87% of cases.3

Focus on common risk factors

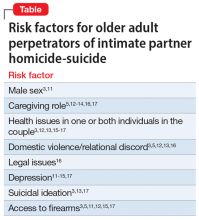

The scarcity and heterogeneity of research regarding older adult homicide-suicide were major limitations to our review. Because most of the studies we identified had a small sample size and limited information regarding the mental health of victims and perpetrators, it would be an overreach to claim to have identified a typical profile of an older perpetrator of homicide-suicide. However, the literature has repeatedly identified several common characteristics of such perpetrators. They are significantly more likely to be men who use firearms to murder their intimate partners and then die by suicide in their home (Table3,5,11-17). Health issues afflicting 1 or both individuals in the couple appear to be a contributing factor, particularly when the perpetrator is in a caregiving role. Relational discord, with or without a history of domestic violence, increases the risk of homicide-suicide. Finally, older perpetrators are highly likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideations.

How COVID-19 affects these risks

Although it is too early to determine if there is a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in homicide-suicide, the pandemic is likely to promote risk factors for these events, especially among older adults. Confinement measures put into place during the pandemic context have already been shown to increase rates of domestic violence18 and depression and anxiety among older individuals.7 Furthermore, contracting COVID-19 might be a risk factor for homicide-suicide in this vulnerable population. Caregivers might develop an “altruistic” motivation to kill their COVID-19–infected partner to reduce their partner’s suffering. Alternatively, caregivers’ motivation might be “egotistic,” aimed at reducing the overall suffering and burden on themselves, particularly if they contract COVID-19.19 This phenomenon might be preventable by acting on the modifiable risk factors.

Continue to: Late-life psychiatric disorders