The authors’ observations

This case was ultimately an accidental ingestion of glipizide, rather than a suicide attempt. The initial suspicion for a suicide attempt had been reasonable in the context of Ms. A’s depressive symptoms, remote history of a prior suicide attempt by ingesting an OTC medication, and toxicologic evidence of ingesting a drug not prescribed to her. Additionally, because of the life-threatening presentation, it was easy to make the erroneous assumption that the ingestion of glipizide must have involved many tablets, and thus must have been deliberate. However, through multidisciplinary teamwork, we were able to demonstrate that this was likely an accidental ingestion by a patient who had an acute febrile illness. Her illness had caused confusion, which contributed to the accidental ingestion, and also caused reduced food intake, which enhanced the hypoglycemic effects of glipizide. Additionally, a lack of awareness of medication safety in the home had facilitated the confusion between the two medication vials.

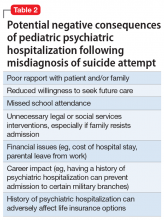

A single tablet of glipizide IR is sufficient to produce profound clinical effects that could be mistaken by medical and psychiatric teams for a much larger and/or deliberate overdose, especially in patients with a psychiatric history. The inappropriate psychiatric hospitalization of a patient, especially a child, who has been mistakenly diagnosed as having attempted suicide, can have negative therapeutic consequences (Table 2). A psychiatric admission would have been misguided if it attempted to address safety and reduce suicidality when no such concerns were present. Additionally, it could have damaged relationships with the patient and the family, especially in a child who had historically not sought psychiatric care despite depressive symptoms and a previous suicide attempt. When assessing for suicidality, consider accidental ingestion in the differential and use specialty expertise and confirmatory testing in the evaluation, taking the pharmacokinetics of the suspected agent into account.

OUTCOME Outpatient treatment

Ms. A’s neurologic symptoms resolve within 24 hours of admission. She is offered psychiatric inpatient hospitalization to address her depressive symptoms; however, her parents prefer that she receive outpatient care. Ms. A’s parents also state that after Ms. A’s admission, they locked up all household medications and will be more mindful with medication in the home. Because her parents are arranging appropriate outpatient treatment for Ms. A’s depression and maintenance of her safety, an involuntary hospitalization is not deemed necessary.

On Day 2, Ms. A is eating normally, her blood glucose levels remain stable, and she is discharged home.

Bottom Line

Oral hypoglycemic agents can cause life-threatening syndromes in healthy patients and can clinically mimic large, intentional overdoses. Clinicians must be aware of the differential of accidental ingestion when assessing for suicidality, and can use toxicology results in their assessment.

Related Resources

- Kidemergencies.com. Emergencies: One pill can kill. http://kidemergencies.com/onepill1.html.

- Safe Kids Worldwide. Medication safety. https://www.safekids.org/medicinesafety.

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. http://www.aapcc.org/.

Drug Brand Names

Glipizide • Glucotrol

Insulin glargine • Lantus

Montelukast • Singulair