EVALUATION Focus on akathisia

On interview by the C-L team, Mr. B is visibly restless, moving all 4 extremities. He reports increased anxiety and irritability over the past 2 to 3 days. Mr. B states that he is aware of his increased motor movements and can briefly suppress them. However, after several seconds, he again begins spontaneously fidgeting, moving all 4 extremities and shifting from side to side in bed, saying, “I just feel anxious.” He denies having visual hallucinations, and says that the previous hallucinations had spontaneously presented and remitted after surgery. He denies the use of psychotropics for mental illness, prior similar symptoms to this presentation, a family history of mental illness, recent illicit substance use, or excessive alcohol use prior to presentation. This history is corroborated by collateral information from his brother, who was present in the ICU. On physical examination, Mr. B is afebrile and his vital signs are within normal limits. He does not have muscular rigidity or neck dystonia. His laboratory values, including complete blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests, and creatine phosphokinase, are within normal limits.

His medication administration record includes 46 standing agents, 16 “as-needed” agents, and 8 infusions. Several of the standing agents had psychotropic properties; however, the most salient were several opioids, ketamine, midazolam, lorazepam, dexamethasone, haloperidol, and olanzapine.

The authors’ observations

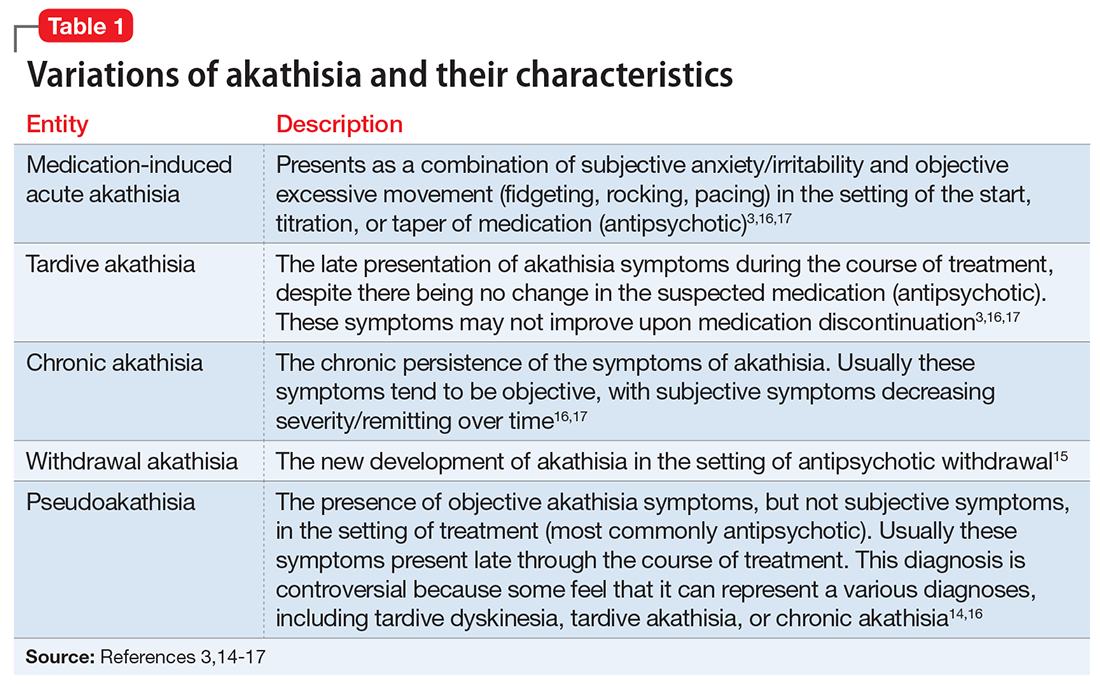

We determined that the most likely diagnosis for Mr. B’s symptoms was medication-induced akathisia secondary to haloperidol. Akathisia, coined by Haskovec in 1901,12,13 is from Greek, meaning an “inability to sit.”12 DSM-5 describes 2 forms of akathisia: medication-induced acute akathisia, and tardive akathisia.3 In the literature, others have described additional classifications, including chronic akathisia, withdrawal akathisia, and pseudoakathisia (Table 13,14-17). In Mr. B’s case, given his sudden development of symptoms and their direct chronologic relationship to antipsychotic treatment, and his combined subjective and objective symptoms, we believed that Mr. B’s symptoms were consistent with medication-induced acute akathisia (MIA). The identification and treatment of this clinical entity is important for several reasons, including reducing patient morbidity and maximizing patient comfort. Additionally, because akathisia has been associated with poor medication adherence, increased agitation/aggression, increased suicidality, and the eventual development of tardive dyskinesia,18 it is a relevant prognostic consideration when deciding to treat a patient with antipsychotics.

Pathophysiologically, we have yet to fully shed light on the exact underpinnings of akathisia. Much of our present knowledge stems from patient response to pharmacologic agents. While dopamine blockade has been linked to akathisia, the exact mechanism is not completely understood. Previous theories linking nigrostriatal pathways have been expanded to include mesocortical and mesolimbic considerations.12,17,18 Similarly surmised from medication effects, the transmitters y-aminobutyric acid, serotonin/5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), norepinephrine, and acetylcholine also have been linked to this syndrome, though as of yet, exact gross pathophysiologic mechanisms have not been fully elucidated.12 More recently, Stahl and Loonen19 described a novel mechanism by which they link the shell of the nucleus accumbens to akathisia. In their report, they indicate that the potential reduction in dopaminergic activity, secondary to antipsychotic administration, can result in compensatory noradrenergic activation of the locus coeruleus.19 The increased noradrenergic activity results in the downstream activation of the shell of the nucleus accumbens.19 The activation of the nucleus accumbens shell, which has been linked to unconditioned feeding and fear behavior, can then result in a cascade of effects that would phenotypically present as the syndrome we recognize to be akathisia.19

Numerous etiologies have been linked to MIA. Of these, high-potency antipsychotics are believed to remain the greatest risk factor for akathisia,18 although atypical antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, have been linked to the disorder.18,19

Continue to: Regarding antipsychotics...