Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 Fluoxetine and paroxetine represented about one-half of the cases; however, there were also cases associated with citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, and venlafaxine. In comparison, there were only 11 reports of hyperprolactinemia associated with tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Although patients were not always symptomatic, the most commonly reported symptoms were galactorrhea (55%), gynecomastia (29%), amenorrhea (11%), mastodynia (11%), and sexual disorders (4%).6 Another study of 5,920 patients treated with fluoxetine found mastodynia in 0.25%, gynecomastia in 0.08%, and galactorrhea in 0.07% of patients.18 Symptoms occurred in an extremely low percentage of patients, and the study is >20 years old.18

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

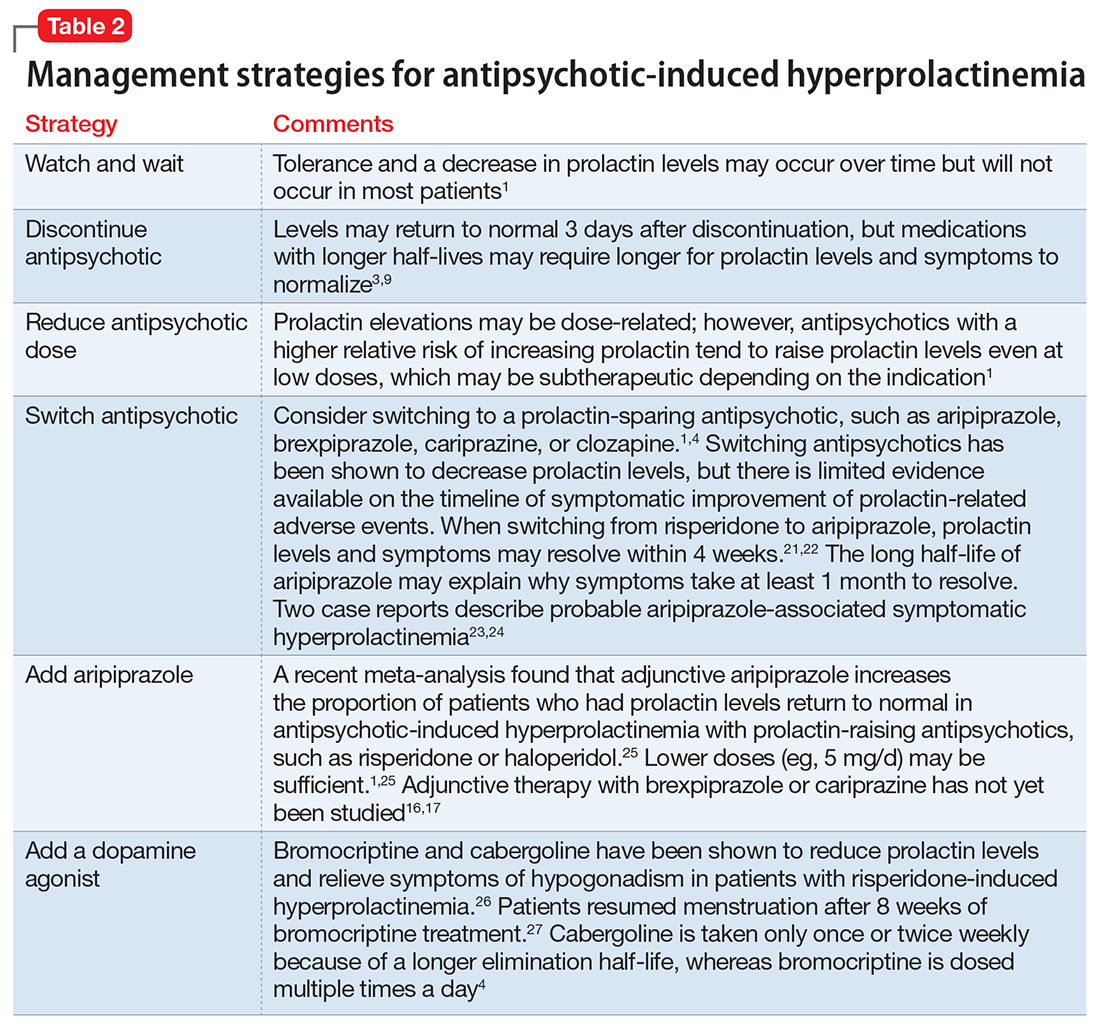

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.