Alternatively, some studies suggest that a difference in dopamine receptor occupancy between typical and atypical antipsychotics leads to different effects on smoking behavior.18 When used long term, typical antipsychotics might increase dopamine receptors or dopamine sensitivity, and thus reinforce the positive effect of nicotine by increasing the number of receptors that can be stimulated, whereas atypical antipsychotics help stimulate the release of dopamine directly through partial agonist of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors.19,20 Atypical antipsychotics also appear to decrease cue-elicited cravings in people who are not mentally ill, whereas haloperidol does not.21

Based on these findings, switching patients with COPD from a typical to an atypical antipsychotic, if feasible, might make smoking cessation more manageable.22 Multiple studies have shown that clozapine is the preferred atypical antipsychotic because it is associated with the most significant decrease in smoking behaviors.23

First-line therapy: Nicotine replacement

Smoking cessation slows the progression of COPD and leads to marked improvements in cough, expectoration, breathlessness, and wheezing.24,25 Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)—gum, inhaler, lozenges, nasal spray, and skin patch—is considered first-line pharmacotherapy. These nicotine substitutes can decrease withdrawal symptoms, although they do not appear to be as effective for light smokers (eg, <10 cigarettes/d), compared with heavy smokers (eg, ≥20 cigarettes/d).26

Long-term smoking abstinence can be improved with combination therapies. A nicotine patch, kept in place for as long as 24 hours, often is used with a nicotine gum or nasal spray. Another option combines the patch with a first-line, non-NRT intervention, such as sustained-release bupropion. Use bupropion with caution in psychiatric patients, however. Do not combine it with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, and do not prescribe it to patients with an eating disorder or history of seizures.26 Bupropion could induce mania in patients with bipolar disorder.

Varenicline, a nicotinic receptor partial agonist indicated to aid in smoking cessation, has been shown to reduce pleasure gained from tobacco as well as cravings. It can increase the likelihood of abstinence from smoking for as long as 1 year, but it also can provoke behavioral changes, depressed mood, and suicidal ideation. These risks—described in an FDA black-box warning of serious neuropsychiatric events—warrant due caution when prescribing varenicline to patients with depression. The FDA also has warned that varenicline could lead to decreased alcohol tolerance and atypically aggressive behavior during intoxication, which is of particular concern because of the high rate of alcohol use among people with SMI.

Motivating and supporting change

When counseling patients with mental illness about smoking cessation, consider unique motivations that, if disregarded, could undermine your efforts. As described above, smoking can ameliorate negative and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with typical antipsychotics. This could explain the significantly higher rates of smoking associated with typical antipsychotics, compared with atypical antipsychotics.27 Patients also could use smoking as self-medication for depression and anxiety. Therefore, take care to offer alternate methods for coping, along with smoking cessation recommendations.22

Screen all adult patients for tobacco use, and offer prompt cessation counseling and pharmacologic interventions.28As a motivational intervention, the “5 As” framework—ask, advise, assess, assist, arrange—can help gauge patients’ smoking status and willingness to quit, as well as emphasize the importance of establishing a concrete, manageable plan.29

Keep in mind the barriers all patients face in their fight to quit smoking, such as nicotine withdrawal, weight gain, and loss of a coping mechanism for stress.29 Patients with schizophrenia can be motivated to quit smoking and participate in treatment for nicotine dependence.30

Besides encouraging smoking cessation, you can educate patients in behaviors that will improve COPD symptoms and management. These include:

- reducing the risk of lung infections through vaccinations (influenza yearly, pneumonia once in adulthood) and avoiding crowds during peak cold and influenza season

- participating in physical activity, which could slow lung function decline

- adhering to prescribed medication

- eating a balanced diet

- seeking medical care early during an exacerbation.

Coaching patients in symptom control

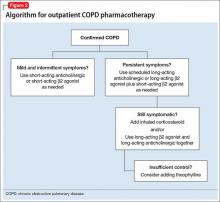

Smoking cessation may have the greatest long-term benefit for patients with COPD, but symptom management is important as well (Figure 2). Pharmacotherapy for COPD usually is advanced in steps, but a more aggressive approach may be necessary for patients presenting with severe symptoms.

Mainstays of COPD therapy are inhaled bronchodilators, consisting of β2 agonists and anticholinergics, alone or in combination. Short-acting formulations are used for mild and intermittent symptoms; long-acting bronchodilators are added if symptoms persist.4 When dyspnea, wheezing, and activity intolerance are not well-controlled with bronchodilators, an inhaled corticosteroid can be tried, either alone or in combination with a long-acting bronchodilator.4

Adherence to medical recommendations is critical for successful COPD management, but inhaled therapy can be difficult for psychiatric patients—especially patients with cognitive or functional impairment. Asking them to demonstrate their inhaler technique can help assess treatment effectiveness.31