HISTORY Low energy, forgetfulness

2 years ago. Mr. M noticed low energy and motivation. He continued to work full-time but thought that it was taking him longer to get work done. He was tapered off escitalopram and started on desvenlafaxine, 50 mg/d; donepezil was increased to 10 mg/d.

The syncopal episodes resolved but blood pressure measured at home averaged 150/70 mm Hg. Mr. M was advised to decrease fludrocortisone from 0.2 mg/d to 0.1 mg/d. He tolerated the change and blood pressure measured at home dropped on average to 120 to 130/70 mm Hg.

1 year ago. Mr. M reported that his memory loss had become worse. He perceived having more stress because of forgetfulness and visual difficulties, which had led him to stop driving at night.

At a follow-up appointment with his psychiatrist, Mr. M reported that, first, he had not tapered escitalopram as discussed and, second, he forgot to increase the dosage of desvenlafaxine. A home blood pressure log revealed consistent hypotension; the psychiatrist was concerned that hypotension could be the cause of concentration difficulties and malaise. The psychiatrist advised Mr. M to follow-up with his PCP and neurologist.

Current admission. Shortly after the visit to the psychiatrist, Mr. M presented to the emergency department for increased syncopal events. Work-up was negative for a cardiac cause. A cosyntropin stimulation test was negative, showing that adrenal insufficiency did not cause his orthostatic hypotension. Chart review showed he had been having blood pressure problems for many years, independent of antidepressants. Physical exam revealed lower extremity ataxia and a bilateral extensor plantar reflex.

What diagnosis explains Mr. M’s symptoms?

a) Parkinson’s disease

b) multiple system atrophy (MSA)

c) depression due to a general medical condition

d) dementia

The authors’ observations

MSA, previously referred to as Shy-Drager syndrome, is a rare, rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 3.7 cases for every 100,000 people worldwide.2 MSA primarily affects middle-aged patients; because it has no cure, most patients die in 7 to 10 years.3

MSA has 2 clinical variants4,5:

• parkinsonian type (MSA-P), characterized by striatonigral degeneration and increased spasticity

• cerebellar type (MSA-C), characterized by more autonomic dysfunction.

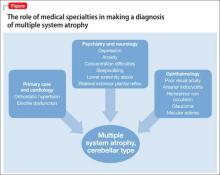

MSA has a range of symptoms, making it a challenging diagnosis (Table).6 Although psychiatric symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria, they can aid in its diagnosis. In Mr. M’s case, depression, anxiety, orthostatic hypotension, and ataxia support a diagnosis of MSA.

Gilman et al6 delineated 3 diagnostic categories for MSA: definite MSA, probable MSA, and possible MSA. Clinical criteria shared by the 3 diagnostic categories are sporadic and progressive onset after age 30.

Definite MSA requires “neuropathological findings of widespread and abundant CNS alpha-synuclein-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions,” along with “neurodegenerative changes in striatonigral or olivopontocerebellar structures” at autopsy.6

Probable MSA. Without autopsy findings required for definite MSA, the next most specific diagnostic category is probable MSA. Probable MSA also specifies that the patient show either autonomic failure involving urinary incontinence—this includes erectile dysfunction in men—or, if autonomic failure is absent, orthostatic hypotension within 3 minutes of standing by at least 30 mm Hg systolic pressure or 15 mm Hg diastolic pressure.

Possible MSA has less stringent criteria for orthostatic hypotension. The category includes patients who have only 1 symptom that suggests autonomic failure. Criteria for possible MSA include parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome in addition to symptoms of MSA listed in the Table, whereas probable MSA has specific criteria of either a poorly levodopa-responsive parkinsonism (MSA-P) or a cerebellar syndrome (MSA-C). In addition to having parkinsonism or a cerebellar syndrome, and 1 sign of autonomic failure or orthostatic hypotension, patients also must have ≥1 additional feature to be assigned a diagnosis of possible MSA, including:

• rapidly progressive parkinsonism

• poor response to levodopa

• postural instability within 3 years of motor onset

• gait ataxia, cerebellar dysarthria, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction

• dysphagia within 5 years of motor onset

• atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons, or cerebellum

• hypometabolism on fluorodeoxyglucose- PET in putamen, brainstem, or cerebellum.6

Diagnosing MSA can be challenging because its features are similar to those of many other disorders. Nonetheless, Gilman et al6 lists specific criteria for probable MSA, including autonomic dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and either parkinsonism or cerebellar syndrome symptoms. Although a definite MSA diagnosis only can be made by postmortem brain specimen analysis, Osaki et al7 found that a probable MSA diagnosis has a positive predictive value of 92% with a sensitivity of 22% for definite MSA.

Mr. M’s symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of probable MSA, cerebellar type (Figure).