The woman in labor should be instructed to refrain from pushing during an attempted maneuver. She can then be instructed to resume pushing following performance of a maneuver to allow determination of whether the shoulder dystocia has been successfully relieved.1

This statement contrasts with claims frequently made by plaintiff medical expert witnesses that the woman experiencing a shoulder dystocia should absolutely cease from pushing.

In a section on team training, the report describes the delivery team’s priorities:

- resolving the shoulder dystocia

- avoiding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic central nervous system injury

- minimizing strain on the neonatal brachial plexus.

Studies evaluating process standardization, the use of checklists, teamwork training, crew resource management, and evidence-based medicine have shown that these tools improve neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Simulation training also has been shown to help reduce transient NBPP (see the box below for more on simulation programs for shoulder dystocia). Whether it also can lower the rate of permanent NBPP is unclear.1

Can simulation training reduce the rate of neonatal brachial plexus injury after shoulder dystocia?

In the new ACOG report on neonatal brachial plexus injury, simulation training is discussed as one solution to the dilemma of how clinicians can gain experience in managing obstetric events that occur infrequently.1 Simulation training also has the potential to improve teamwork, communication, and the situational awareness of the health-care team as a whole. Several studies over the past few years have shown that, in some units, the implementation of simulation training actually has decreased the number of cases of neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP), compared with no simulation training.

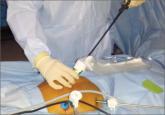

For example, Draycott and colleagues explored the rate of neonatal injury associated with shoulder dystocia before and after implementation of a mandatory 1-day simulation training program at Southmead Hospital in Bristol, United Kingdom.2 The program consisted of practice on a shoulder dystocia training mannequin and covered risk factors, recognition of shoulder dystocia, maneuvers, and documentation. The training used a stepwise approach, beginning with a call for help and continuing through McRoberts’ positioning, suprapubic pressure, and internal maneuvers such as delivery of the posterior arm (Figure).

There were 15,908 births in the pretraining period and 13,117 in the posttraining period, with shoulder dystocia rates comparable between the two periods. Not only did clinical management of shoulder dystocia improve after training, but there was a significant reduction in neonatal injury at birth after shoulder dystocia (30 injuries of 324 shoulder dystocia cases [9.3%] before training vs six injuries of 262 shoulder dystocia cases [2.3%] afterward).2

In another study of obstetric brachial plexus injury before and after implementation of simulation training for shoulder dystocia, Inglis and colleagues found a decline in the rate of such injury from 30% to 10.67% (P<.01).3 Shoulder dystocia training remained associated with reduced obstetric brachial plexus injury after logistic-regression analysis.3

Shoulder dystocia training is now recommended by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations in the United States. However, in its report, ACOG concludes—despite studies from Draycott and colleagues and others—that, owing to “limited data,” “there remains no evidence that introduction of simulation can reduce the frequency of persistent NBPP.”1

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Executive summary: neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):902–904.

- Draycott TJ, Crofts FJ, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):14–20.

- Inglis SR, Feier N, Chetiyaar JB, et al. Effects of shoulder dystocia training on the incidence of brachial plexus palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):322.e1–e6.

The report reaffirms the previous statement from the ACOG practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia, which asserts that no specific sequence of maneuvers for resolving shoulder dystocia has been shown to be superior to any other.6 It does note, however, that recent studies seem to demonstrate a benefit when delivery of the posterior arm is prioritized over the usual first-line maneuvers of McRoberts positioning and the application of suprapubic pressure. If confirmed, such findings may alter the standard of care for shoulder dystocia resolution and result in a change in ACOG recommendations.

The ACOG report stresses the importance of accurate, contemporaneous documentation of the management of shoulder dystocia, observing that checklists and documentation reminders help ensure the completeness and relevance of notes after shoulder dystocia deliveries and NBPP. ACOG has produced such a checklist, which can be found in the appendix of the report itself.1