Other causes. It is unclear how brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Some think they arise in response to infectious agents such as toxoplasmosis, coxsackievirus, mumps, pertussis, or mycoplasma pneumonia.2 Some assume a mechanical cause, such as fetal response to longstanding abnormal intrauterine pressure exerted by maternal conditions such as bicornate uterus and uterine fibroids, especially in the lower segment.1,2

When brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia, they likely originated before labor and delivery.4 Some experts suggest serial electromyelograms within the first 7 days of life to establish a prenatal rather than intrapartum etiology. A positive electromyelogram within 1 week of birth would suggest antepartum causation.2,9

Recognizing risk factors for shoulder dystocia best way to reduce injury

Most brachial plexus injuries or impairments are associated with shoulder dystocia,9 and shoulder dystocia is the most common way brachial plexus injuries are introduced into litigation.

Decreasing the number of brachial plexusrelated liability cases, therefore, depends on decreasing the incidence of shoulder dystocia. Unfortunately, a failsafe method continues to elude both clinicians and researchers.10-12

Retrospective studies have identified certain factors that may—but do not necessarily—increase the risk of shoulder dystocia.

Prenatal risk factors include high maternal or paternal birth weight, maternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, advanced age, short stature, multiparity, postdates, prior shoulder dystocia, small pelvis, prior delivery of a macrosomic infant, gestational diabetes in an earlier pregnancy, abnormal blood sugars in the current pregnancy, or fetal macrosomia.13,14-16

Intrapartum risk factors include a rapid or prolonged second stage, failure or arrest of descent, presence of considerable molding, and need for a midpelvic delivery.10,15

Predictability. Prospective studies have not established the predictability of shoulder dystocia. A 2000 study17 showed that 55% of cases with 1 or more risk factors experienced shoulder dystocia. Predictability increases somewhat when both maternal diabetes and fetal macrosomia complicate pregnancy, since the rate of shoulder dystocia in women with diabetes is consistently higher than in nondiabetic gravidas. This becomes a significant issue when the infant weighs more than 4,000 g.

Indications for prophylactic cesarean in women with diabetes

In 1999, Wagner et al9 found that 70% of shoulder dystocias in women with diabetes occurred when the fetal weight exceeded 4,000 g. They concluded that cesarean delivery for infants with an estimated weight over 4,250 g would reduce the rate of shoulder dystocia by 75% and increase the cesarean delivery rate by 1%.

Others are more conservative. Gross and colleagues11 suggested that, for every additional 26 cesarean deliveries, only 1 case of shoulder dystocia would be prevented.

Macrosomia. Most obstetricians and researchers still do not advocate prophylactic cesarean delivery for macrosomia alone because, by some estimates, 98% of macrosomic infants are delivered without difficulty.18 However, they do suggest that obstetricians at least consider the possibility of cesarean delivery for a macrosomic fetus when the woman has diabetes.

In a study completed in 2000, Skolbekken19 suggested a cutoff of 4,250 g for women with diabetes. Dildy20 suggested limits of more than 4,500 g for diabetic women and more than 5,000 g for nondiabetic gravidas. However, Conway and Langer21 assert that a cutoff of 4,500 g is too liberal for women with diabetes and maintain that, at this cutoff, 40% of shoulder dystocias would not be prevented.

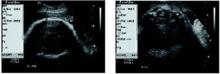

• Ultrasound measurements. Since estimates of fetal weight have a margin of error approaching 40%,9 others have chosen different parameters for determining fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes. In a retrospective study involving 31 women with gestational diabetes, Cohen et al22 found that subtracting the fetal biparietal diameter from the abdominal diameter—with both measurements obtained via ultrasound—yields a predictability score higher than estimated fetal weight. Specifically, if the difference between the 2 measurements is 2.6 cm or more, the rate of shoulder dystocia is high enough to warrant elective cesarean (FIGURE ).

FIGURE Using ultrasound measurements to predict macrosomia

A simple way to predict fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes is to subtract the fetal biparietal diameter (9.3 cm in the scan at left) from the abdominal diameter (average of 12.44 cm in the scan at right). If the difference exceeds 2.6 cm, elective cesarean is warranted. In this case it is 3.14 cm, indicating elective cesarean is warranted.

When dystocia occurs, have a plan and stick to it

Shoulder dystocia immediately places both mother and neonate at risk for temporary or permanent injury. Thus, it is imperative that all obstetricians and other health-care providers who deliver infants have a well developed plan of action for this emergency. They should immediately ask for obstetric assistance and instruct the mother to discontinue any pushing.