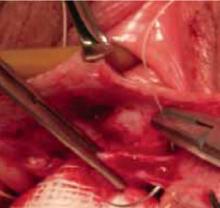

FIGURE 5 Begin plication at the apex

Plication begins at the apex with vertical mattress stitches. Use 3-0 prolonged delayed absorbable or permanent suture in the anterior wall.

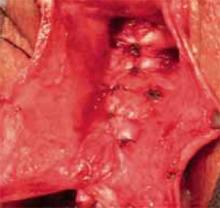

FIGURE 6 The reduced cystocele

The cystocele reduced following midline plication of the vaginal muscularis. The excess vagina is then trimmed and closed with interrupted 3-0 absorbable suture.

Functional surgical outcomes

Because of the long association between anterior wall prolapse and SUI, most surgeons evaluate patients preoperatively to determine the need for concomitant incontinence procedures. As a result, the literature reporting surgical cystocele repair via anterior colporrhaphy frequently uses continence of urine as the functional outcome. This is not surprising considering that anterior repair and Kelly plication, as reported by Howard Kelly more than 75 years ago, have been the gold standard for surgical correction of anterior wall prolapse and SUI.

In a series of 194 SUI patients who underwent anterior colporrhaphy, Beck11 found that adding a modified Kelly plication, including a vaginal retropubic urethropexy, increased the cure rate for SUI from 75% to 94%. Unfortunately, he did not report the anatomic success of the anterior colporrhaphy.

Kohli et al12 also retrospectively examined patients who had undergone anterior colporrhaphy with and without needle bladder-neck suspension. Although the cure rate for SUI was not reported, patients who underwent concomitant needle suspension had a higher rate of recurrent cystocele: 33% (n = 40) versus 7% (n = 27). Investigators theorized that retropubic dissection at the time of transvaginal needle suspension resulted in an iatrogenic paravaginal defect and denervation of the anterior vaginal wall.

The risks of needle suspension. A randomized controlled trial by Bump et al8 also suggests that needle suspension should be avoided. In that trial, 29 patients with stage 3 and 4 prolapse were randomized to needle colposuspension or endopelvic fascia plication. They, too, found that needle colposuspension carried a higher rate of recurrent anterior prolapse. Further, it did not reduce the rates of SUI compared with fascia plication.

Although incontinence surgery performed at the time of cystocele repair will reduce the rates of de novo incontinence, the higher rates of cystocele recurrence associated with some procedures warrants judicious preoperative planning. Clearly, needle suspension should not be performed as an incontinence procedure or repair of anterior wall prolapse. Whether other vaginal incontinence procedures, eg, midurethral slings, lead to recurrence of anterior wall prolapse deserves further investigation.

Anatomic outcomes

Midline colporrhaphy. Because anterior colporrhaphy is rarely performed alone, few series describe patients having undergone simply an anterior repair. Stanton et al13 followed 54 women for up to 2 years after they underwent traditional midline plication with vaginal hysterectomy for prolapse. Eight (15%) of the women had recurrent anterior wall prolapse.

Colombo et al14 randomized 71 women with clinical SUI and stage 2 or 3 prolapse to Burch colposuspension or anterior colporrhaphy with Kelly plication. All women were followed for at least 8 years. The cure rate for SUI was 86% for the Burch procedure, compared with 52% for anterior repair and Kelly plication. However, 12 (34%) women treated with Burch colposuspension and 1 (3%) treated with anterior colporrhaphy had recurrent cystocele of grade 2 or 3 with or without prolapse at other vaginal sites.

Abdominal paravaginal repair. Shull15 followed 149 women for 6 months to 4 years after they underwent abdominal paravaginal repair with the urethrovesical stitch brought through Cooper’s ligament for treatment of SUI and paravaginal cystocele. He reported a 5% recurrence of anterior wall prolapse.

In another series, Shull16 reported on 62 women who were followed for a mean of 18 months after abdominal paravaginal repair. Four of 57 (7%) had recurrent vaginal prolapse to the hymen.

In a cohort of 102 patients evaluated with the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitative Examination (POP-Q) at our institution, the maximal point of prolapse was the anterior wall in 60% of cases; the apex and posterior wall each accounted for roughly half the remaining cases (unpublished data).

Ellerkmann et al30 reported on 237 consecutive patients who presented with symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse. In 77 women (33%), anterior compartment pelvic organ prolapse predominated; 46 patients (19%) had posterior compartment prolapse; and 22 patients (11%) had apical prolapse.

Hendrix et al31 analyzed patients from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and found that the anterior compartment predominated over the posterior compartment. In a follow-up study from the WHI, Handa32 reported on 412 women followed for 2 to 8 years. Among those who entered the WHI protocol without cystocele, 1 in 4 was diagnosed with it at some point in the study. This compares to 1 in 6 for rectocele and 1 in 100 for uterine prolapse. The majority of all defects were grade 1 or relaxation above the hymen.