Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

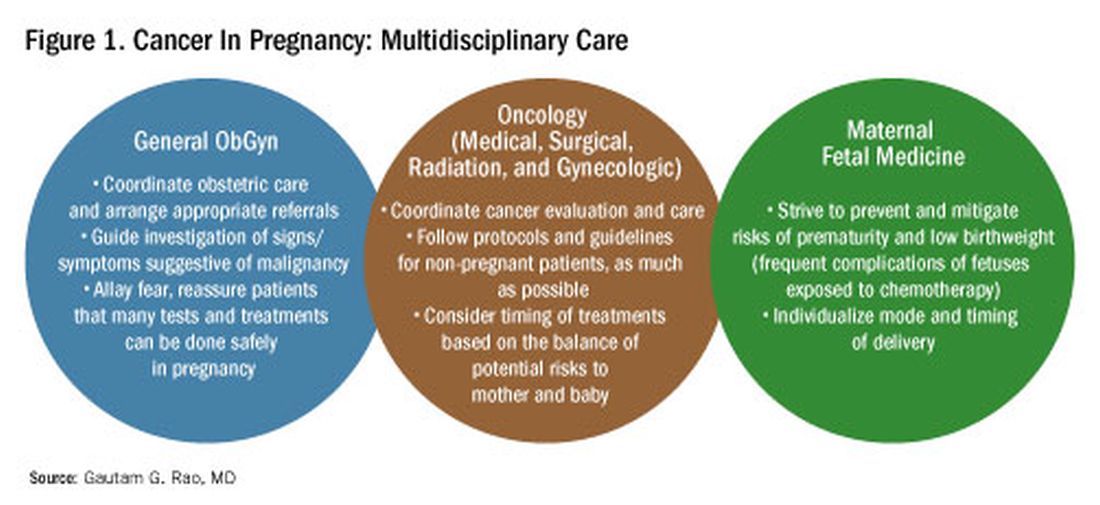

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.