Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume

The large body of literature on volume and outcomes has led to a number of public health initiatives aimed at reducing perioperative morbidity and mortality. Broadly, these efforts focus on regionalization of care, targeted quality improvement, and the development of minimum volume standards. Each strategy holds promise but also the potential to lead to unwanted consequences.

Regionalization of care

Recognition of the volume-outcomes paradigm has led to efforts to regionalize care for complex procedures to high-volume surgeons and centers.10 A cohort study of surgical patterns of care for Medicare recipients who underwent cancer resections or abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from 1999 to 2008 demonstrated these shifting practice patterns. For example, in 1999–2000, pancreatectomy was performed in 1,308 hospitals, with a median case volume of 5 procedures per year. By 2007–2008, the number of hospitals in which pancreatectomy was performed declined to 978, and the median case volume rose to 16 procedures per year. Importantly, over this time period, risk-adjusted mortality for pancreatectomy declined by 19%, and increased hospital volume was responsible for more than two-thirds of the decline in mortality.10

There has similarly been a gradual concentration of some gynecologic procedures to higher-volume surgeons and centers.11,12 Among patients undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in New York State, 845 surgeons with a mean case volume of 3 procedures per year treated patients in 2000. By 2014, the number of surgeons who performed these operations declined to 317 while mean annual case volume rose to 10 procedures per year. The number of hospitals in which women with endometrial cancer were treated declined from 182 to 98 over the same time period.11 Similar trends were noted for patients undergoing ovarian cancer resection.12 While patterns of gynecologic care for some surgical procedures have clearly changed, it has been more difficult to link these changes to improvements in outcomes.11,12

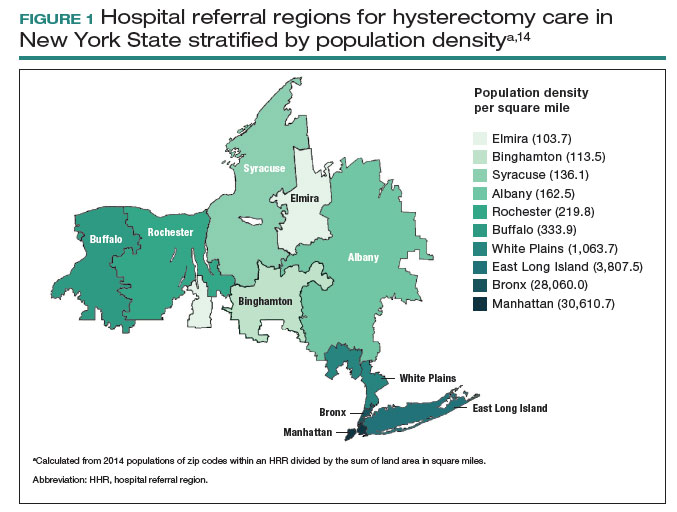

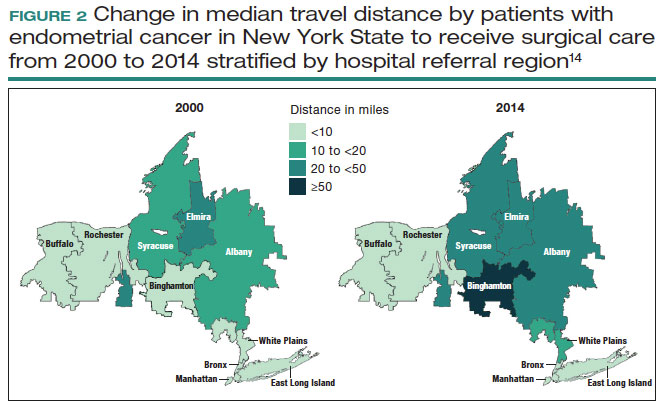

Despite the intuitive appeal of regionalization of surgical care, such a strategy has a number of limitations and practical challenges. Not surprisingly, limiting the number of surgeons and hospitals that perform a given procedure necessitates that patients travel a greater distance to obtain necessary surgical care.13,14 An analysis of endometrial cancer patients in New York State stratified patients based on their area of residence into 10 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which represent health care markets for tertiary medical care. From 2000 to 2014, the distance patients traveled to receive their surgical care increased in all of the HRRs studied. This was most pronounced in 1 of the HRRs in which the median travel distance rose by 47 miles over the 15-year period (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 2).14

Whether patients are willing to travel for care remains a matter of debate and depends on the disease, the surgical procedure, and the anticipated benefit associated with a longer travel distance.15,16 In a discrete choice experiment, 100 participants were given a hypothetical scenario in which they had potentially resectable pancreatic cancer; they were queried on their willingness to travel for care based on varying differences in mortality between a local and regional hospital.15 When mortality at the local hospital was double that of the regional hospital (6% vs 3%), 45% of patients chose to remain at the local hospital. When the differential increased to a 4 times greater mortality at the local hospital (12% vs 3%), 23% of patients still chose to remain at the local hospital.15

A similar study asked patients with ovarian neoplasms whether they would travel 50 miles to a regional center for surgery based on some degree of increased 5-year survival.16 Overall, 79% of patients would travel for a 4% improvement in survival while 97% would travel for a 12% improvement in survival.16

Lastly, a number of studies have shown that regionalization of surgical care disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients and those with low socioeconomic status.12,13,17 A simulation study on the effect of regionalizing care for pancreatectomy noted that using a hospital volume threshold of 20 procedures per year, a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic patients than White patients would be required to travel to a higher-volume center.13 Similarly, Medicaid recipients were more likely to be affected.13 Despite the inequities in who must travel for regionalized care, prior work has suggested that regionalization of cancer care to high-volume centers may reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival for some cancers.18

Targeted quality improvement

Realizing the practical limitations of regionalization of care, an alternative strategy is to improve the quality of care at low-volume hospitals.5,19 Quality of care and surgical volume often are correlated, and the delivery of high-quality care can mitigate some of the influence of surgical volume on outcomes.

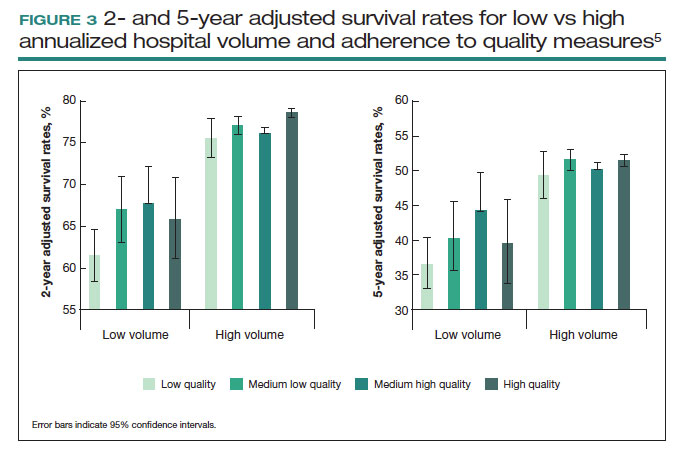

These principles were demonstrated in a study of more than 100,000 patients with ovarian cancer that stratified treating hospitals into volume quintiles.5 As expected, survival (both 2- and 5-year) was highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals (FIGURE 3).5 Similarly, quality of care, measured through adherence to various process measures, was also highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals. Interestingly, in the second-fourth volume quintile hospitals, there was substantial variation in adherence to quality metrics. Among hospitals with higher quality care, an improved survival was noted compared with lower quality care hospitals within the same volume quintile. Survival at high-quality, intermediate-volume hospitals approached that of the high-volume quintile hospitals.5

These findings highlight the importance of quality of care as well as the complex interplay of surgical volume and other factors.20 Many have argued that it may be more appropriate to measure quality of care and past performance and outcomes rather than surgical volume.21

Continue to: Minimum volume standards...