CASE Fetal anomalies detected on ultrasonography

A 34-year-old woman (G2P1) at 19 weeks’ gestation presented for fetal anatomy ultrasonography evaluation. Ultrasonography demonstrated fetal demise with fetal size less than dates, oligohydramnios, and what appeared to be a full-thickness herniation of the thoracic and abdominal contents. Due to the positioning of the fetus and the oligohydramnios, the fetus appeared to have ectopia cordis and herniated liver and bowel; the bladder was not visualized. The patient was counseled regarding the findings and the suspected diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell. After counseling, the patient expressed desire to bury the fetus intact according to her religious custom. She underwent a successful uterine evacuation with misoprostol administration and delivered a nonviable fetus that had a closed thoracic cage without ectopia cordis. Key findings were a very short 2-vessel umbilical cord without coiling that was tethered to the intra-abdominal organs, “pulling” the internal organs out of the abdomen, and lack of an anterior abdominal wall (FIGURE 1). Given these findings, a final diagnosis of body-stalk anomaly was made.

Fetal abdominal wall defects (AWDs) encompass a wide array of congenital defects, although they all involve herniation of 1 or more intra-abdominal content through a ventral abdominal defect.1 Overall, the estimated incidence of AWDs is approximately 6 per 10,000 births.1 Gastroschisis and omphalocele are the most common of these defect types.2

The majority of AWDs can be diagnosed during the first trimester of pregnancy via ultrasonography; however, during the first trimester the physiologic midgut herniation resolves by 12 weeks of gestation. It is therefore important to repeat imaging at a later gestational age to confirm the suspicion. Furthermore, the differential diagnosis should include the relatively benign condition of umbilical hernia.

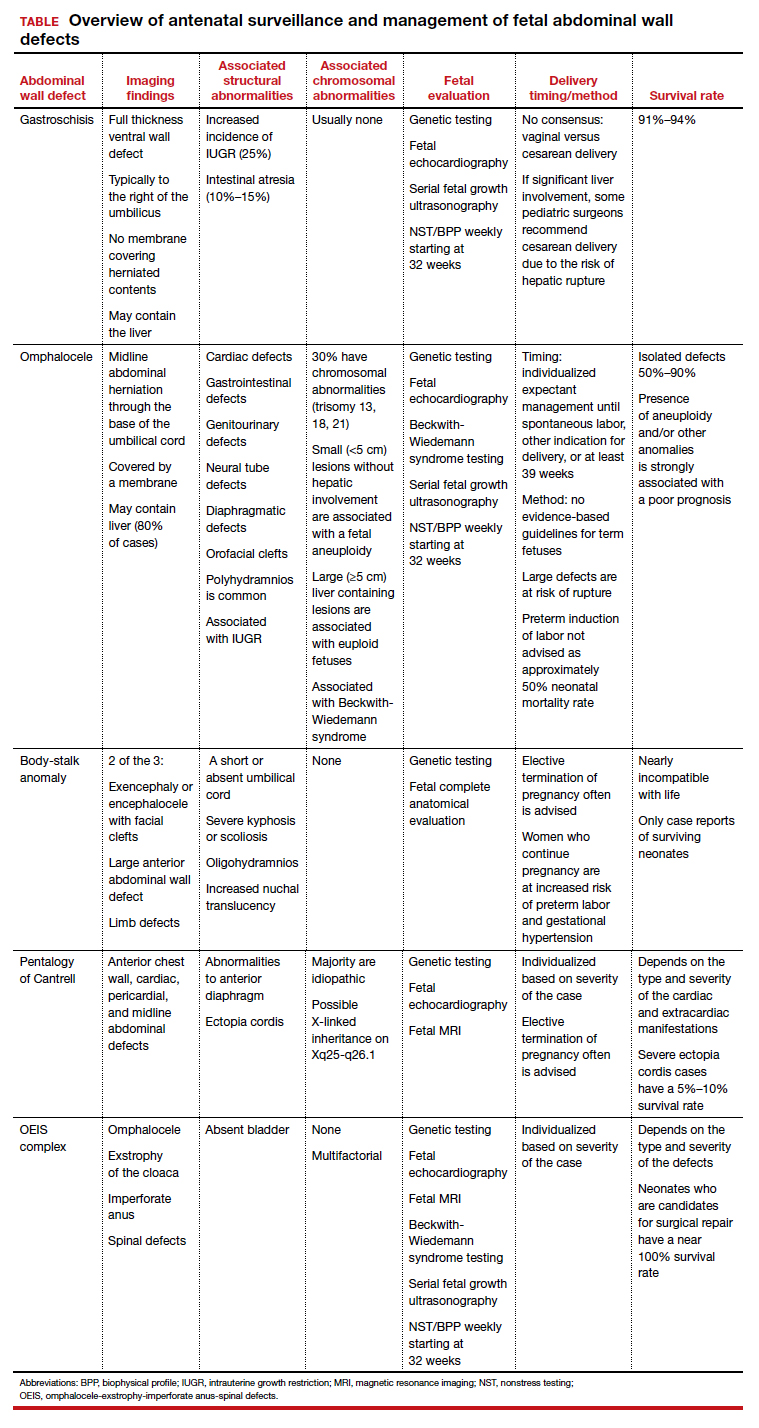

While many AWDs share similarities, they differ significantly in prognosis and management. Early detection is therefore crucial for fetal surveillance, prenatal testing, perinatal planning, and patient counseling (TABLE). In this article, we outline antenatal surveillance and management of AWDs based on recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine as well as on our experience and practice.

Gastroschisis is an increasingly prevalent AWD

Gastroschisis is a full-thickness, ventral wall defect that results in bowel evisceration; it typically occurs to the right of the umbilical cord insertion.3 It is one of the most common AWDs and its prevalence has increased in the past few decades, from 2 to 3 cases per 10,000 live births in 1995 to as high as 6 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.2,4,5

The cause of gastroschisis remains unclear. The main theory is that there is an ischemic disruption of the closure of the abdominal wall at or near the omphalomesenteric artery or the right umbilical vein.6,7 In addition, investigators have reported an increased incidence of gastroschisis in mothers exposed to cigarette smoking and certain medications, such as pseudoephedrine, salicylates, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen.8,9

Continue to: Making the diagnosis...