CASE 1 Patient’s pain continues after endometriosis excision

A 32-year-old woman (G1P1) reports having CPP for 8 years. She underwent excision of stage 1 endometriosis last year, which resulted in a modest improvement in pain for 6 months. Her pain is worse during menses, at the end of the day, and with vaginal intercourse (both during and lasting for 1 to 2 days after). On examination, you find diffuse pelvic floor tenderness but no adnexal masses or rectovaginal nodularity on palpation.

What treatment options would you consider for this patient?

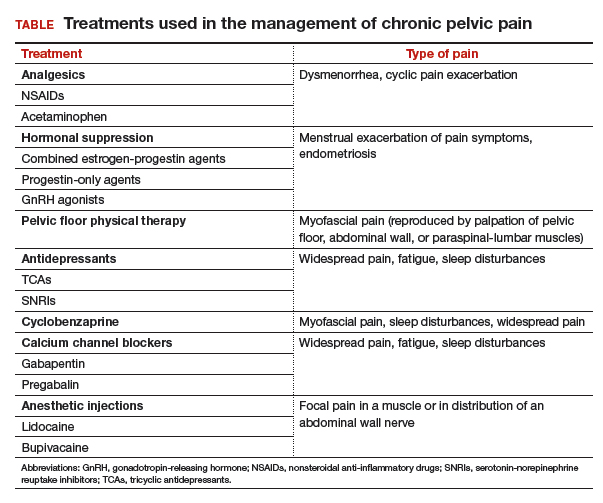

Multimodal treatment often needed to manage CPP symptoms

The patient described in Case 1 may benefit from a combination of therapies that include analgesics, hormone suppression agents, and physical therapy (PT) (TABLE).

Analgesics

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen and naproxen, work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzyme, which decreases assembly of peripheral prostaglandins and thromboxane. In a large Cochrane review, NSAIDs were associated with moderate or excellent pain relief for approximately 50% of patients with dysmenorrhea, and they have been shown to reduce menstrual flow due to decreased production of uterine prostaglandins.13 There is little evidence for use of NSAIDs in chronic pain conditions.

Acetaminophen’s mechanism of action is unclear, but the drug likely inhibits central prostaglandin synthesis, and it works synergistically with other analgesics.

Opioids act on μ and δ opioid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems as well as in the gastrointestinal system. No evidence supports opioid use in CPP or other chronic pain conditions. Long-term opioid use is associated with a multitude of adverse effects, risk for dependence, and the induction of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (in which patients develop greater sensitivity to pain stimuli).

Analgesics, specifically NSAIDs, can be considered for use in patients with dysmenorrhea, cyclic pain exacerbation, or a suspected inflammatory component of pain. Best practices include scheduling NSAID use before the onset of menses and continuing the drugs on a scheduled basis throughout. NSAIDs should be used for a brief period, and regular use on an empty stomach should be avoided.

Hormone suppression

Many types of hormone suppression therapy are available, including combined estrogen-progestin medications, progestin-only medications, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and antagonists.

Combined estrogen-progestin medications include oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), vaginal rings, and transdermal patches. Combined estrogen-progestin methods cause atrophy of eutopic and ectopic endometrium and suppress GnRH.

Progestin-only methods include oral formulations, the levonorgestrel intrauterine device, intramuscular and subcuticular injections, and subdermal implants. Progestin-only methods lead to atrophy of eutopic and ectopic endometrium.

A GnRH agonist, leuprolide depot works by downregulating luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone release from the pituitary, causing suppression of ovarian follicular development and ovulation, leading to a hypoestrogenic state.

Combined estrogen-progestin formulations and progestin-only options are often considered first-line therapy for dysmenorrhea and endometriosis.13 Continuous administration, with the goal of inducing amenorrhea, is effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that different types of hormone suppression agents are, essentially, equally effective.13–15 Treatment recommendations therefore should focus on adverse effects, cost, and patient preference. GnRH agonists and norethindrone are not FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis.

It may be appropriate to consider use of hormone suppression therapy in patients with menstrual exacerbation of pain symptoms, including those with a history of endometriosis. We generally advise patients that the goal is amenorrhea and that achieving it often involves a process of trying different formulations to find the best fit. Remember that GnRH agonists are dependent on a functional hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, and they are unlikely to be effective in women with suspected residual endometriosis who have had a bilateral oophorectomy.

Physical therapy

For CPP, PT typically targets musculoskeletal dysfunction in the pelvic floor, abdominal wall, hips, and back. Interventions include muscle control, mobilization, and biofeedback. Pelvic PT has been shown to improve pain and dyspareunia in patients with CPP, coccydynia, and vestibulodynia.16–18 One large study found a significant, patient-directed decrease in pain medication use after pelvic floor PT.19 Pelvic PT for patients with interstitial cystitis and pelvic floor tenderness resulted in improved pain and bladder symptoms.20

Pelvic PT can be considered for patients with pain reproducible with palpation of the pelvic floor, abdominal wall, paraspinal-lumbar muscles, or sacroiliac joints. Best practices include referral to a therapist who has specialized training in CPP, including pelvic floor therapy. It is important to clearly list the indication for referral, as many of these therapists also treat stress urinary incontinence. The wrong exercises can result in increased hypercontractility of pelvic floor muscles, which can worsen pelvic pain.

It is also critical to clarify expectations with your patient at the time of PT referral. Specifically, advise patients that when beginning therapy, it is common to experience a temporary increase in discomfort of the pelvic muscles. Inform patients also to expect that their therapist will perform internal manipulation of the pelvic floor muscles through the vagina, as this can be surprising for some patients. Finally, counsel patients that their adherence to daily home exercises improves their chance of a durable, long-term successful response.21

CASE 1 Treatment recommendations

For treatment of this patient’s CPP, consider scheduled naproxen therapy during menses, continuous OCPs, and referral for pelvic floor PT.

Read about treating a case of pain, sleep disturbance, and depression.