Steps in recovery for the second victim

Based on a semistructured interview of 31 physicians involved in adverse events, Scott and colleagues described the following 6 stages of healing5:

Chaos and accident response. Immediately after the event, the physician feels a sense of confusion, panic, and denial. How can this be happening to me? The physician is frequently distracted, immersed in self-reflection.

Intrusive reflections. This is a period of self-questioning. Thoughts of the event and different possible scenarios dominate the physician’s mind. What if I had done this or that?

Restoring personal integrity. During this phase, the physician seeks support from individuals with whom trusted relationships exist, such as colleagues, peers, close friends, and family members. Advice from a colleague who has your same level of expertise is precious. The second victim often fears that friends and family will not be understanding.

Enduring the inquisition. Root cause analysis and in-depth case review is an important part of the quality improvement process after an adverse event. A debriefing or departmental morbidity and mortality conference can trigger emotions and increase the sense of shame, guilt, and self-doubt. The second victim starts to wonder about repercussions that may affect job security, licensure, and future litigation.

Obtaining emotional first aid. At this stage, the second victim begins to heal, but it is important to obtain external help from a colleague, mentor, counselor, department chair, or loved ones. Many physicians express concerns about not knowing who is a “safe person” to trust in this situation. Often, second victims perceive that their loved ones just do not understand their professional life or should be protected from this situation.

Moving on. There is an urge to move forward with life and simply put the event behind. This is difficult, however. A second victim may follow one of these paths:

- drop out—stop practicing clinical medicine

- survive—maintain the same career but with significant residual emotional burden from the event

- thrive—make something good out of the unfortunate clinical experience.

Related article:

TRUST: How to build a support net for ObGyns affected by a medical error

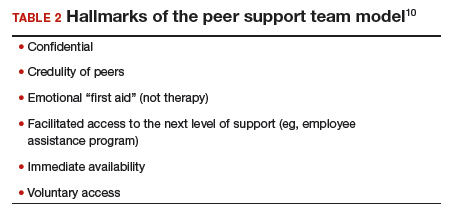

All these programs offer immediate help to any clinician in psychological distress. They provide confidentiality, and the individual is reassured that he or she can safely use the service without further consequences (TABLE 2).10

The normal human response to an adverse medical event can lead to significant psychological consequences, long-term emotional incapacity, impaired performance of clinical care, and feelings of guilt, fear, isolation, or even suicide. At some point during his or her career, almost every physician will be involved in a serious adverse medical event and is at risk of experiencing strong emotional reactions. Health care facilities should have a support system in place to help clinicians cope with these stressful circumstances.

Use these 5 strategies to facilitate recovery

- Be determined. No matter how bad you feel about the event, you need to get up and moving.

- Avoid isolation. Get outside and interact with people. Avoid long periods in isolation. Bring your team together and talk about the event.

- Sleep well. Most symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder occur at night. If you have trouble falling asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares related to the event, attempt to regulate your body’s sleep schedule. Seek professional help if needed.

- Avoid negative coping habits. Sometimes people turn to alcohol, cigarettes, food, or drugs to cope. Although these strategies may help in the short term, they will do more harm than good over time.

- Enroll in activities that provide positive distraction. While the mind focuses on the traumatic event (this is normal), you need to get busy with such positive distractions as sports, going to the movies, and engaging in outdoor activities. Do things that you enjoy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.